Currently absorbed in the Dickensian classic, Great Expectations, I find myself seamlessly alternating between the real world and the adventures of Pip, the young protagonist, in a Victorian England as alien to me as the ruins of Mohenjo-daro. As though at the snap of a finger, I am transported from my modest Mumbai bedroom to an elegant parlour in a mansion in London owned by a rather churlish old woman named Miss Havisham. That, or perhaps taking a stroll in the lawns of her mansion with its neatly manicured lawns. In between reading actual story snippets, of course!

The late ’90s was a time when instant messaging was the rage, albeit on bulky computers that took longer to get started than whipping up a two-minute Maggi meal. Pretty amazing, that era; one day I was in love with Gayatri; the next, Kathleen!

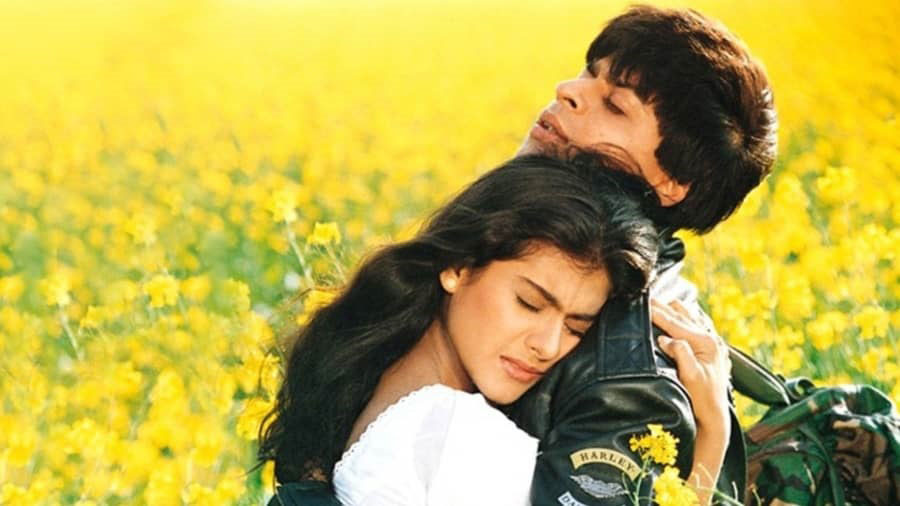

More had been lost in translation than the mere colour of her hair

Plenty was lost in translation back then. For instance, I thought about how a certain girl I felt especially close to, had blonde hair. Never mind the fact that the girls around me were predominantly brunettes. It might have been her first name, which could have easily passed as British, perhaps even American. I would envisage her shaking her head, those golden strands of hair flying all around, like in the Liril ad…

My eyes blindfolded in the real world, you would not believe what I saw in the virtual. A couple of months on, that blonde stood me up. More had been lost in translation than the mere colour of her hair.

Bruce Springsteen talks about women having a “secret garden” they hide from their suitors. To quote him:

If you pay the price

She’ll let you deep inside.

But there’s a secret garden she hides

No matter how much we try, or so The Boss would have us believe, we cannot enter that sacrosanct garden. Oh, and guys can have gardens, too. Maybe not with lawns as neatly manicured as those in my endearing Dickensian tale, but lawns nonetheless.

Might our partners not keep from us a mystery about themselves, so that we can gaily dig into the recesses of our imaginations and splatter the sketches of our loves in our minds with some truly fantastic hues?

Sometimes all people need is having someone listen to them at the end of a grueling day’s work

Love is often about reaffirmations through simple, everyday questions, feels the author Pixabay

Over the course of several chats, I got to know quite a bit about some online loves. I imagined kissing them and taking them out for fancy dinners, but you know what the best part was? I actually liked them for what they said, for words as precious as any Dickens might have written.

In a popular Netflix show, Love is Blind, contestants speed date in interconnected pods. Unable to see their counterparts, they focus on engaging them in conversations that might or might not lead somewhere. I watched the latest season, and it only reaffirmed my belief. That love is indeed blind.

Sometimes all people need is having someone listen to them at the end of a grueling day’s work. Asking them if they had that Chana Salad they had packed is a lover’s way of showing that they care, but also a means of feeling the love themselves. No matter who it is they are speaking to.

The loves of their lives or the compromises they made.

Stories abound of Japanese men falling in love with inflatable dolls. In some cases, where the men are married. While I, for one, would never advocate something of the kind to anyone searching for love, it might just be the best thing that happened to those men. Probably because their wives said: ‘Sayonara’!

While it is no matter of debate that the doll is not actually listening to what their paramour is saying, there is also no questioning the fact that its gentleman lover has found a way to express his feelings. Even if he knows that he is a blind man talking.

Sending across love emojis, instead of mouthing ‘I love you’?

Can virtual love be more real than the real thing, asks the author Pixabay

The reason digital love works is because it allows you to speak your mind, while keeping certain emotions well-masked. You send across love emoticons and keep the person guessing if your love for them is real at all. Usher in that element of mystery, so to speak. After all, the last time they received a certain emoji you sent might well have been from their bhajiwali. Is that what we really want, though? Sending across love emojis, instead of mouthing “I love you”? Virtual kiss emojis instead of our tongues in their mouths? Which love is more real?

Currently, I am thoroughly enjoying my time in Victorian England. Although I am a mere observer of Pip’s fascinating encounters with several folk, including the dainty Estella, I think I have perfectly captured the essence of his story. And yet, another reader reading the same lines might have a completely different version of the tale in their minds. Such is the vast expanse of love and the Dickensian world.

I wish I could have a cup of tea with Dickens some time to understand what he was thinking.

What I am learning from Dickens, however, is that all one can do is interpret love their way. Your husband might have invited your best friend over for dinner simply because he is besotted with her. Or because he has found a genuine friend in her. You will never know.

Never once is it mentioned that the lawns of Miss Havisham’s manor (in the book) are neatly manicured. I made it up. In love, we create mansions that are the grandest of our lives’ fictions.

Even though they might be architecturally unsound. No stopping those exquisite English tea parties, scones et al.

Love has a rabbit hole we fall into every now and then. Dragging us into a surreal world that blends the real with the phantasmagoric. In pursuit of love’s blind spot.

After all, we are all Dickensian stories, each one of us. Like readers, our hapless lovers weave the most exquisite fictions around us. With great expectations.

Rohit Trilokekar is a novelist from Mumbai who flirts with the idea of what it means to love. His heart’s compass swerves ever so often towards Kolkata, the city he believes has the most discerning literary audience.