“Like charity, conservation begins at home,” said wildlife and natural history filmmaker Ashwika Kapur regarding her latest film, Catapults to Cameras, which had its first screening at the Phoenix Hall of The Saturday Club on the evening of January 7. Ashwika, a Kolkata girl who has won a ‘Green Oscar’ in addition to several other awards for her outstanding work over the years, shared how she wants to focus more on local stories, which is why “this story from south Bengal is so close to my heart”.

Converting animals from targets into subjects

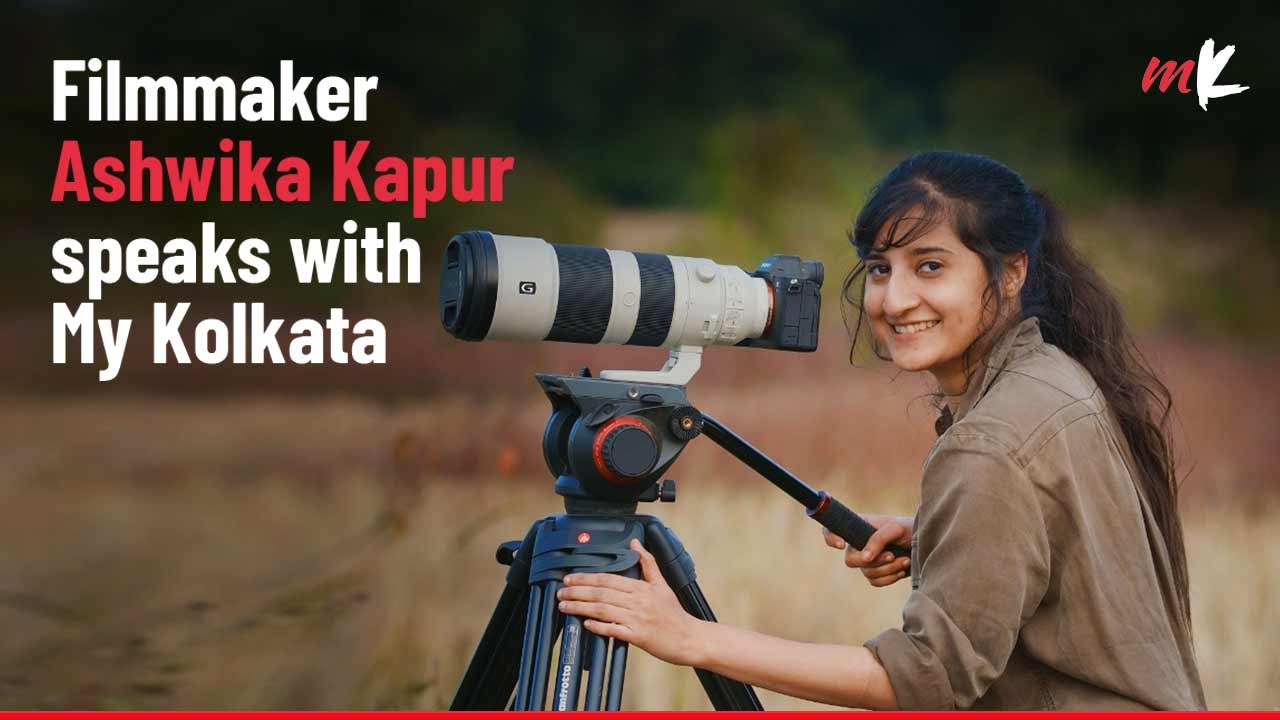

Ashwika welcoming the audience ahead of the first screening of her latest film at The Saturday Club Soumyajit Dey

Directed and produced by Ashwika, Catapults to Cameras is the first feature-length film by RoundGlass Sustain, which documents India’s wildlife and habitats through articles, photographs and videos to tell holistic stories about sustainability and conservation. The crux of the film revolves around Ashwika’s journey to a village in south Bengal and her interaction with five adolescent boys, whose catapults are replaced with cameras in an attempt to change their perspective towards animals.

The film, which blends footage from the ground with a voiceover from Ashwika, begins on a grim note, revealing the widespread nature of wildlife hunting festivals in south Bengal. Thousands of men, some accompanied by their kids, hunt in hoards at these festivals, not for food but to be a part of a blood sport. From birds to mammals to reptiles, no species is spared in what Ashwika describes as “the shocking extent of the massacre”.

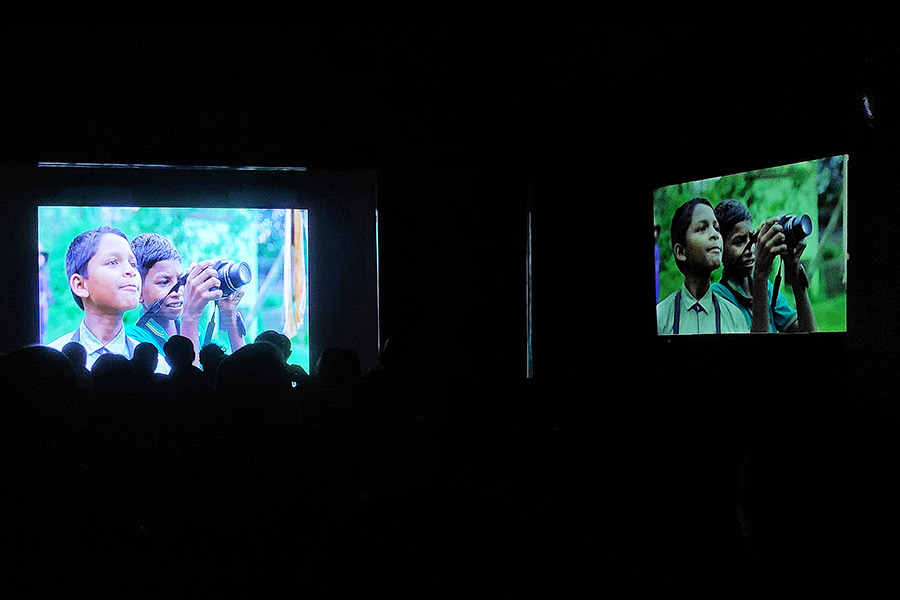

The five children in the film prove how conservation begins with compassion Soumyajit Dey

Once the five boys enter the narrative, it is clear how they are taught from infancy to look at animals as targets, with their catapults acting as the tools with which they channelise their animosity towards wildlife. But Ashwika, with conservationist Suvrajyoti Chatterjee for company, decides to spring a surprise on the boys by presenting them with cameras and asking them to convert their “targets into subjects”. After a few amusing photography lessons, the boys show off their skills, capturing everything from birds and cows to snakes and elephants. In the process, they start to empathise with the very creatures they had been brought up to attack.

The climax of the film provides a heartwarming resolution to Ashwika’s initiative, highlighting how children can become changemakers. It also serves as a poignant reminder that there is no better catalyst for conservation than compassion.

‘Local stories rarely make it to television’

(L-R) Poonam Singh, Ashwika, Arka Sarkar, Meghna Banerjee and Suvrajyoti Chatterjee Soumyajit Dey

“Generally, a project leads to a documentary being made about it, but in this case, a documentary has led to becoming a project,” observed thespian Poonam Singh, while moderating a post-screening conversation with Ashwika and members of the Human and Environment Alliance League (HEAL) — Suvrajyoti Chatterjee, Meghna Banerjee and Arka Sarkar. A non-profit organisation established as a charitable trust in 2017, HEAL focuses on “biodiversity conservation, mitigation of human-animal conflict and enforcement of wildlife and environmental laws”. The discussion shed light on how Ashwika and HEAL are taking forward their project in south Bengal, the challenges they had to encounter during the filming as well as the diversity of Bengal’s wildlife, which needs urgent attention.

The evening concluded with an interactive session with the audience, which included the likes of actor Victor Banerjee, Atri Bhattacharya, additional chief secretary to the government of West Bengal; Andrew Fleming, the British deputy high commissioner to Kolkata; Debanjan Chakrabarti, director, British Council, East and Northeast India; and advocate Siddhartha Mitra. Among the questions posed to Ashwika was a query from Fleming, who lauded the film and wanted to know why such stories do not become a part of “big, shiny television”. “Local stories rarely make it to television, especially stories that have some sort of a conflict. What goes on TV [in the wildlife genre] usually involves big, charismatic animals that have a global appeal,” responded Ashwika, who nonetheless reaffirmed her commitment to tell more stories closer to home.