In Summer of 2018, American research scholar and occasional Calcutta resident Andrew Otis published Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper. The book is about a muckraking Irishman named James Augustus Hicky, who for two short years between 1780 and 1782 challenged the foundations of the British Empire.

Hicky reported on British Governor General Warren Hastings’s administration, embezzlement in the church, and the Supreme Court of Calcutta. Apart from this, the newspaper recorded the ongoing events of everyday life and people in the city at the time — a valuable primary source of history. It was one of the first recorded instances of a weekly newspaper in Asia that led the way for a democratic free press in Independent India.

What followed was a host of legal cases for Hicky — recorded by his lawyer William Hickey (no relation to him). During his undergraduate days, Otis found the attorney’s memoirs in the basement of his university in Rochester, New York. This led to five years and research in a host of countries including India, Germany, and the US to bring this story to life.

Otis’s book was well received, especially by the media and academics both in Bengal and across South Asia. It sold over 3,000 copies — consistent numbers for a non-fiction history book in India. Recently, the book has been reprinted in the Indian subcontinent after the rights had been acquired by a new publisher.

Karthik Venkatesh is an executive editor associated with Hicky’s Bengal Gazette since the project’s inception. In his opinion, there is a paradigm shift which is apparent in how people are contributing to the stock of knowledge in the Global South. He credits Otis’s success to his reliance on primary archival sources and familiarity with speaking and reading Bengali.

When this book was first released five years ago, the author was at a crossroads in his life. Otis was about to embark on a PhD program at the University of Maryland in Washington DC. Fast forward to late 2022 — armed with a doctorate in hand, he intends to return to Calcutta for more archival work based on the 1781 Rebellion against the East India Company.

Andrew Otis

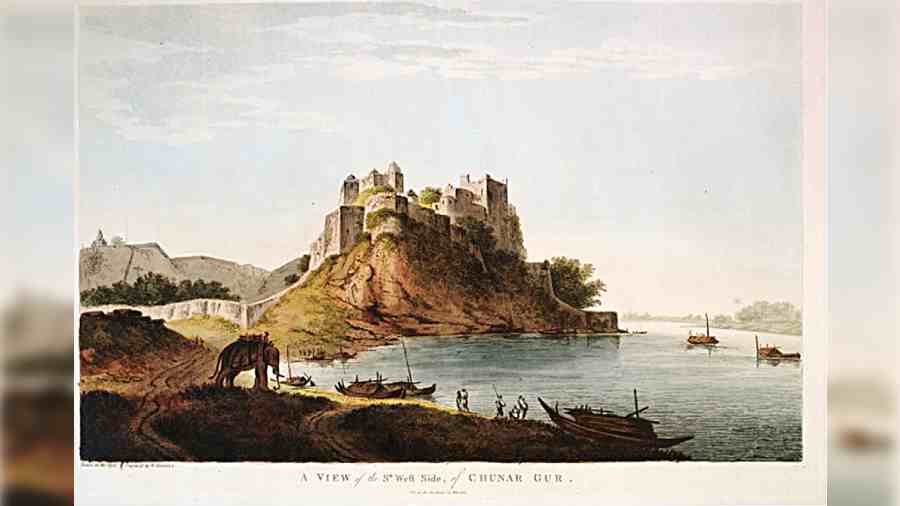

Speaking from his home in DC, the soft-spoken scholar is excited at the prospect of coming back to the city for more research. Most folks are familiar with the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny. Much less is known about the 1781 Rebellion. Otis argues that this rebellion came closer to its goals. The rebels nearly captured Hastings. The accompanying visuals are paintings of the Fort of Chunar, near Benares on the Ganges, attributed to William Hodges sometime between 1780 and 83. This is where Hastings held out while being besieged by rebels in 1781.

Crediting his doctoral experiences for lessons in diligence and efficiency, Otis speaks about a transition away from history to more contemporary issues. One of the biggest challenges the news industry worldwide faces today is a crisis of trust. In free societies and democracies, a free press is essential. People don’t trust the press because they think it is biased. His dissertation hypothesised that if search engines present biased articles with labels explaining that the articles come from a newspaper’s opinion section, it might improve societal trust in the news media and, therefore, help democratic societies.

His current role as a researcher for The Chronicle of Higher Education is a stark contrast from academia. This is a US news magazine which covers issues that affect colleges, universities, and students. News moves quicker than academic publishing. His role is to conduct data analysis to improve audience engagement with their journalism. In Otis’s words, research which would normally take years is compressed into weeks.

Apart from his full-time job, he is preoccupied with the notebooks of Judge John Hyde of the Supreme Court of Bengal. Readers of Hicky will be familiar with Hyde.

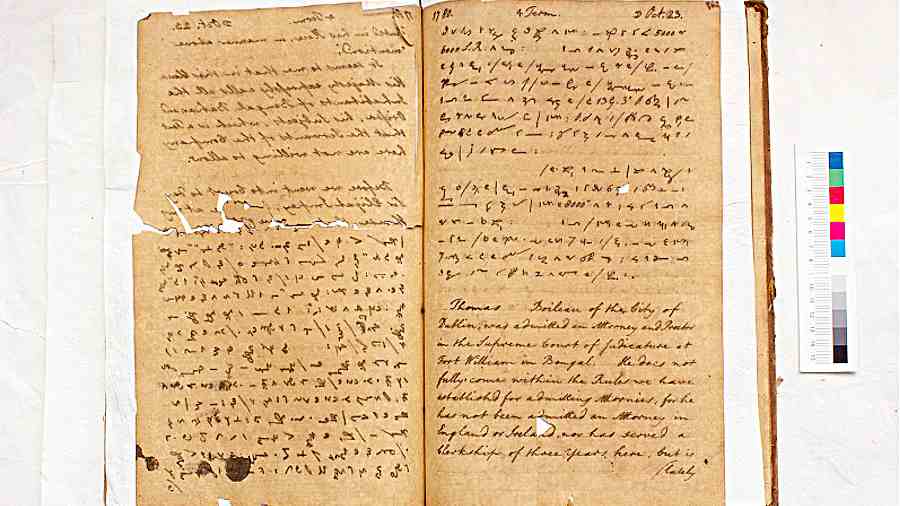

A page from Hyde’s Notebooks showing Hyde’s secret shorthand. Source: The Victoria Memorial, Calcutta

His notebooks detail the goings on at the Supreme Court at the time. Founded by the British government in 1773, the court’s primary purposes were to bring English rule of law to India and to check the power of the East India Company.

It did so for seven years before it was corrupted by Hasting’s administration. Three judges that made up the Supreme Court were offered bribes. Two accepted while Hyde refused out of honesty. These notebooks give details on cases that were heard at the Supreme Court. Details of his fellow judges are mentioned in shorthand — this was a secret code to record the corruption of his fellow judges. Attached is an image which shows a page from the handbook. This image is from the Victoria Memorial in Calcutta.

Alongside Carol Johnson, who is a professor at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, Otis has been working on an academic paper on Hyde’s secret shorthand in his notebooks which is currently under peer review at a journal. This shorthand shows how the history of India’s legal system developed. The researchers theorise that India could have been developed differently had there been an unbiased court protecting free speech and the right to a fair trial.

Otis also hopes to publish his work in the US and the UK. Nothing would make him happier to walk into his local bookstore in DC and find his writing on their shelves. Citing Lau Chingri and Mochar Ghonto as can’t-miss food on his list, he speaks about fond memories of living in Calcutta. Readers could hope to see the scholar in the city for a book tour sometime this year.