Editor’s Note:

Art Cinema and India’s Forgotten Futures is a history of “art films” and the robust film-culture that grew around cinema in post-Independence India. It is also an analysis of film as a way of doing history. Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, and Ritwik Ghatak are central figures in the book. Each was widely influential within Indian film circles through their many writings, film society work, and filmmaking. While critical literature often pits these figures against one another as if they were counterpoints, Majumdar sees them as each others’ necessary counterparts. The three men engaged polemically with one another in print; they also dedicated essays and books to one another. The following excerpt shows the passionate debates about their work, especially within film society circles:

The excerpt:

Unsurprisingly, films by [Ritwik] Ghatak, [Satyajit] Ray, and [Mrinal] Sen occupied disproportionate space in these debates [over good cinema, in the 1950s].

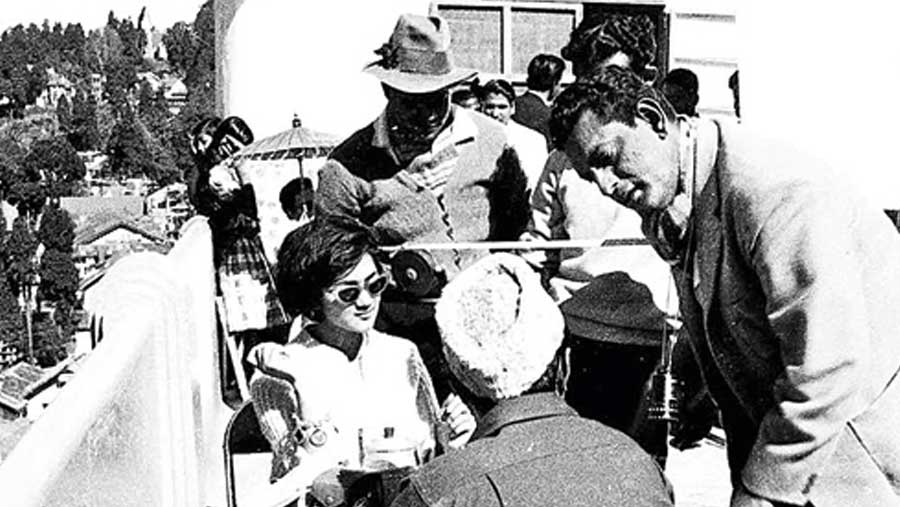

Even though Ray was by the mid-sixties the most renowned of the three, his global success did not guarantee him favorable reception at home. During 1959– 73, he made several films which opened to strong criticism from Calcutta’s film-society critics. According to Ashok Rudra, a Bengali economist interested in cultural debates, Ray gave no evidence in most of his films of “any comprehension” of contemporary India’s social problems or of “any capacity or inclination to tackle them.” The only exceptions were Kanchenjungha (1961) and Devi (1959). The former centered on the tensions that unfold during a middleclass family’s vacation in Darjeeling, a hill station famous for its views of the Himalayan peaks, and the latter on the deification of a young woman by her patriarchal father-in-law as a goddess with miraculous powers that ultimately drove her to suicide. Yet, argued Rudra:

“Satyajit Ray in a pensive mood,” Montage, Anandam, Bombay.

One could have taken Kanchanjungha as a seriously optimistic film if it were shown that the characters were trying to find ways out for themselves by consciously changing the constricting and inhibiting environmental conditions, of course, to the extent possible. But nothing like that is done. Problems are posed, and they get simply resolved . . . and the only factor accounting for the miracle seems to be the magnificent beauty of the Kanchanjungha. If this is the way Ray would like to be humanist . . . there is indeed very little we can hope for from him in the line of treatment of modern problems.

Satyajit Ray on the sets of 'Kanchenjungha' The Telegraph archives

Not one to remain silent, Ray offered a feisty response to Rudra. “I should have thought,” he noted, “the very elements of the film—the near fairy-tale setting, the holiday mood, the two-hour span of the narrative, the fact that the characters have been divorced from their normal surroundings—would debar expectation of a realistic thrashing out of the problems . . . I am afraid Sri Rudra will have to search long and hard for the kind of film he is looking for: the vast lumbering saga in which every problem will be thrashed out . . . every emotional conflict played out, each to its ultimate limit; in which the sweet little child who does not understand today will, as Sri Rudra puts it, ‘understand one day,’ and then she will cease to be sweet, she will become unhappy, gloomy, and full of complexes.”

Ray was repeatedly criticized for his alleged failure to address social realities. The desire for political cinema, rather than “superb craftsmanship” in filmmaking, was the main reason behind many film society activists’ disappointment with Ray, whom they derided, despite his success with international and domestic audiences, as a “bourgeois” filmmaker. A film like Ashani Sanket (1973), based on the famine of 1943, epitomized for many film society viewers Ray’s tendency to aestheticize, through his impeccable cinematic sensibility, the horrors of a man-made famine. They had hoped that the film would act as an allegory for the food riots of the 1960s. As one disappointed commentator wrote in Frontier: “We all hoped that we would again find the man who stood with his head high leading the silent procession in memory of the food movement martyrs in 1966. But alas, the procession has marched forward. The leader has straggled behind.” My focus here is on the controversy their films generated in film society circles.

If Ray was generally viewed in film society circles as lacking in political radicalism, this was not a charge that faced Mrinal Sen. Sen, more than any other filmmaker of the time, engaged with the politics of the Maoist-inclined Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) (CPI [M-L]). His technique of utilizing news clippings and documentary footage was praised as avant-garde. Referring to his two films Padatik (The Guerrilla Fighter, 1973) and Calcutta 71 (1972), the same Ashok Rudra who had criticized Ray wrote, “what gets reflected . . . is precisely the auto-criticism that is taking place among the ranks of the party.” He compared Sen to Godard as a director “who at the height of professional success, renounced film making for entertainment and money making, and is using it strictly as an instrument of political action.”

Special issue on Mrinal Sen, Chitrabikshan, Cine Central Film Society, Calcutta

But even Sen could not satisfy all his left-leaning film society comrades. Some questioned the fact that the FFC financed his films. In the words of one commentator, “When the ruling power is witch-hunting the extremists throughout the country . . . destroying all genuine freedom of speech and expression, it is a matter of great wonder that they will finance Mr. Sen’s effort at glorifying the cause of the extremists.” Seeing Sen as a stooge of the establishment, this writer concluded, “it may well be that in these days of sophistication it is the well-considered policy of the government not to come to a direct confrontation with the intellectuals, but to slowly win them over.” It is worth quoting some more passages from this letter from one Probodh Dhar Chakraborty from Howrah if only to highlight the tone of the criticism:

The message of both Calcutta 71 and Padatik (Sen’s films) is shrouded in abstract intellectualism. . . . Though it deals with serious themes as poverty and revolution, Calcutta 71 fails to convince any one of any ideal to fight for a new world. Padatik may well be an object of hot discussion in coffee houses, cafes, and restaurants but it can never be an inspiration for revolutionaries.

…

The director who emerges as the most favored in film society writings was Ritwik Ghatak. There were several reasons for this. First, the producer of most of Ghatak’s films was Pramod Lahiri, a member of the Cine Club of Calcutta. This made it easy for film societies to exhibit Ghatak’s films. Second, many regarded Ghatak to be true breakaway from the dominant modes of narrative cinema established by Hollywood or Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta.

The female face in Ghatak. Left, Subarnarekha; right: Jukti Takko Aar Gappo. Courtesy of NFAI, Pune.

Let me just flag some salient features of Ghatak’s oeuvre here to help the reader understand his appeal to film societies. Ghatak started out as a communist cultural worker with IPTA and then came into filmmaking with Nagarik, completed in 1952, but released posthumously in the 1970s. Ghatak’s later films wove in multiple themes of the decline that had set in postcolonial Bengali bhadralok (respectable) lives that resonated deeply with film society audiences. His background in IPTA made him introduce theater as topos within his films, where many dramatic crises unfolded, forcing his audiences to ponder the problems facing political theater in India in the face of more commercially viable forms of entertainment.

According to Kumar Shahani, who studied with Ghatak during the latter’s stint at the Poona Film Institute, and who was an active member of the Anandam film society, Ghatak’s work constituted a defiant assertion of identity that challenged both indigenous and Western structures of domination. “In an atmosphere where our cultural attitudes and artifacts have been identified with the objectification of effete Brahminism and European humanism inflicted on us Debating Radical Cinema 121 by the colonials, Ritwikda’s work is the violent assertion of our identity. It is the cry of the dying girl in Meghe Dhaka Tara that echoes through the hills, our right to live.”

Ghatak’s signature framing -Meghe Dhaka Tara. Courtesy of NFAI, Pune.

Excerpted with permission from 'Art Cinema and India's Forgotten Futures: Film and History in the Postcolony' by Rochona Majumdar, Published by Columbia University Press, INR 699, Pages 304. All photographs and captions excerpted, except Kanchenjungha.