Set in Kolkata, The Lady on the Horse and Other Secrets, is a family saga which spans five generations of the Lahiri family. D.N. Lahiri is determined to amass the wealth and status of zamindars. His grandson, Hemanta Lahiri, prides himself on being a Brown Sahib. Kanailal Mitra wants to burn down the Raj. And Balaram Das can’t seem to avoid being at the wrong place at the wrong time. The novel explores the insidious implications of class and caste, through the lives of people thrown together by blood ties and fate lines.

The following excerpt follows the advent of a young girl into Lahiri Bari, as a wife for the eldest Lahiri boy. The tutor’s son Kanailal (rudely called Kak for his dark skin and unruly hair) disapproves of the alliance; not that it matters because he is not in fact a Lahiri. D.N. Lahiri’s middle son, Pradeep, finds his brother’s wife as ridiculous as she finds him. Meanwhile, outside the gates of this mansion in north Kolkata, the freedom struggle wages on — it is a phenomenon that consumes Kak entirely and manages to pique an ironic interest in Pradeep. At the centre of it all, the narrative plumbs the idea that everything which happens in the present also has its roots in the past — every generation must confront its own trials and be shaped by the legacy it has been bequeathed.

*****

A house in north Kolkata that the Lahiris might have lived in Mathures Paul

D.N. Lahiri, who had a low opinion of formal education to begin with, decided that it was time for his eldest son to spend less time at home and more time at the shop, where he could meet their eminent clients and, as it turned out, the daughters who happened to accompany them. When D.N. genially invited Jane Harrington to come play with his sons one afternoon (assuming that the English did not frown upon their girls and boys cavorting together), Debananda rallied his brothers around for a game of hide and seek. Eager to make up for his tongue-tied appreciation at the shop, Debananda squeezed himself behind the statue of a bored angel with Jane, who was thrilled with their hiding place until he tried to kiss her. She went scampering back to find her father immediately, and 14-year-old Debananda lived in trepidation for weeks, waiting for D.N. to come bearing down on him, until Kak pointed out, in his characteristically brusque manner, that no English girl was going to publicly admit to being pawed by a native boy. The epiphany made Debananda very angry and he didn’t speak to Kanai for months, later insisting it was Jane who had tried to kiss him. Since Pritilata’s departure coincided closely with the petting of Jane, Debananda would tell his wife that his mother’s departure had crushed him, that he had almost eloped with an English girl who had fallen in love with him, but good sense prevailed. And Kamala would feel grateful that the universe had intervened on her behalf, for it had been preordained that she be a Lahiri wife.

Kamala arrived at Lahiri Bari looking like a little doll in an orange saree and small gold bangles. Pradeep and Ratan stared more than was considered polite, even for boys. Kak bristled at the idea of a child bride, waxing eloquent about obsolete traditions and regressive choices, all of which was confusing for Pradeep, who thought it might be silly to ask why one shouldn’t marry young if one was going to marry at all. Six years later, when a law was passed to prevent girls younger than 14 from being wedded, Kak would be smug because that put both Debananda and Kamala on the other side of the law. By then, Kak himself would have fallen in love with a woman a whole month older than him… the most revolutionary thing Pradeep could ever dream of doing.

When Kamala, the human plaything, arrived, Mashima moved into the rooms overlooking the inner courtyard, officially instituting the female quarters. This was also where Timpa, Rimpa and Tumpa shredded the spinach, washed the clothes, and stirred the kheer, all of them jumping up to answer when their names (or anything that sounded like it) rang through the house. Mashima taught Kamala how to oversee the maids and also to embroider flowers on cloth, saying her husband would like that. But Debananda showed little interest in Kamala’s attempts at sewing a lotus on a bedsheet, which made his young wife sulk. Pradeep, taking a break from Mastermoshai’s homework, felt sorry for this lost little doll with the pinchable cheeks and petulant mouth, and tried to take an interest in her needlework. It was a deathly boring affair, tracing the uneven lines of blue thread along the stiff white cotton, so he showed her a picture of his mother instead, the one Kak had secretly taken, the one he was most proud of. Kamala studied the photograph for long minutes, with a furrowed brow, before saying, “Who’s this strange creature?” Pradeep felt a rush of uncharacteristic rage, which was quickly displaced by a surge of defiance. He took his photograph back with trembling hands and walked away from the puzzled little girl.

Kamala and Pradeep would never be friends; over time, the chilling animosity he felt towards his brother’s wife dulled to a cool indifference, while she wrote him off as the oddity who’d clearly inherited his mother’s mad genes. There was little opportunity for Kamala and Pradeep to get under each other’s feet because Kamala was pregnant after three months, shortly after (as Kak indelicately pointed out, in outrage) the commencement of her period cycle. Increasingly, most of the goings-on at Lahiri Bari were outrageous to Kak, as his own pursuits might have been to the Lahiris, if any of them had had an inkling about the kind of people he had begun to fraternise with — the kind frustrated with Gandhi’s passive non-cooperation, the kind itching to set people and places aflame. When Rajendranath Lahiri (clearly no relative of D. N. Lahiri’s) was arrested for bombs unearthed in houses in Dakshineswar and Sovabazar, a trembling Kak dragged Pradeep to the secret passage in the library and swore him to secrecy in furious whispers — if they came after him, then Pradeep would have to be his alibi, his cover, that it was his duty to protect Kak and, therefore, his country. Fifteen-year-old Pradeep, staring at the crude bombs, revolvers and explosives the passage now housed, felt nothing but a curious feeling of satisfaction. He couldn’t help thinking how kicked his mother might be if she knew about this… not that he would ever be able to tell her in his letters. It seemed that the Lahiris had found themselves inadvertently embroiled in the struggle for a freedom they thought they didn’t need.

Pradeep enjoyed his passive role in Bengal’s revolution, chuckling to himself every time his father was entertaining Englishmen in his library, entirely in the dark about what, or sometimes who, lay beyond the bookshelf which he had stuffed with the kind of books his father was unlikely to ever touch — lofty poetry and spiritual counsel. Occasionally Pradeep would accompany Kak to a rare event, such as joining the crowds at Howrah Station to witness the arrival of Jatin Das’s hunger-struck corpse, and found himself adding his voice to the roars of “down with imperialism” and “long live the revolution”, much to Kak’s amusement.

*****

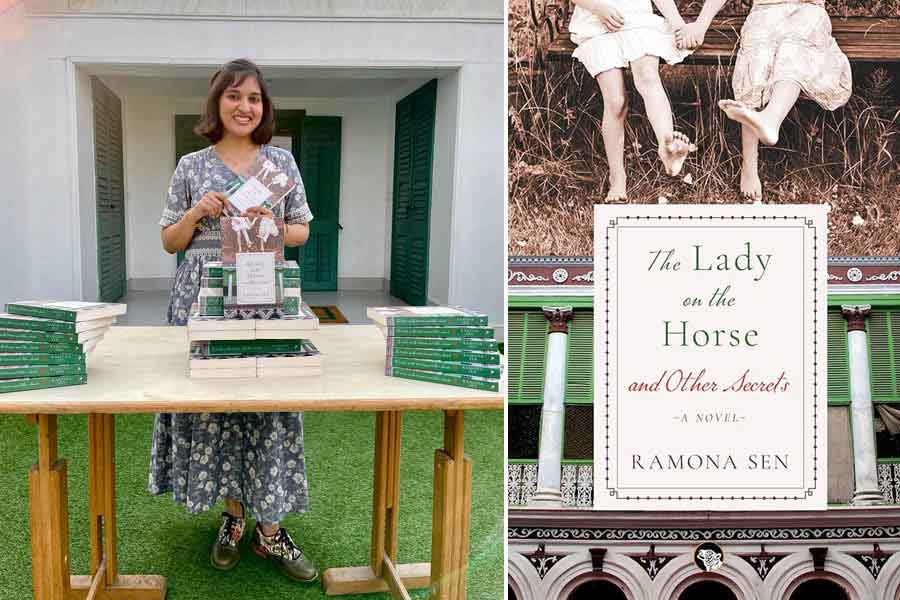

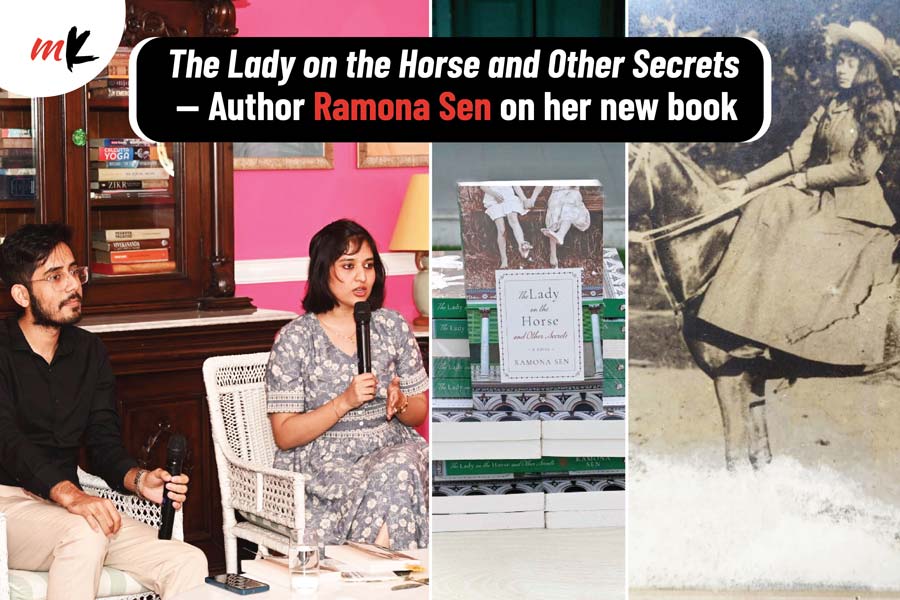

Extracted from The Lady on the Horse and Other Secrets: A Novel by Ramona Sen. Published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2024.

Buy the book here.