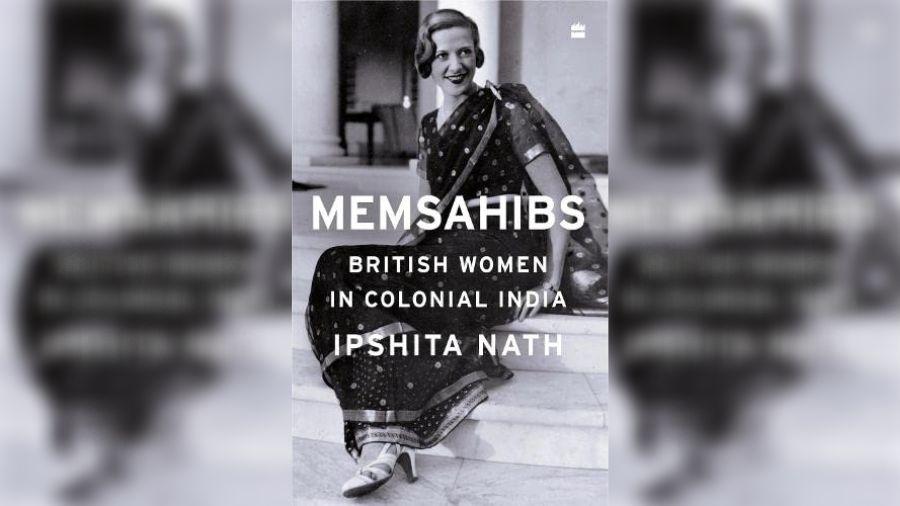

Even 75 years after Independence, a curiosity about the British Raj lingers. We might find ourselves wondering about the lives of ancestors who lived under British dominance, and sometimes even the lives of the servants of the Raj. In her book Memsahibs, Ipshita Nath casts light on colonial rule from the eyes of the Englishwomen who followed their husbands to the unknown east. These women were in fact the original Memsahibs. Later of course, the word gathered various connotations.

As Nath describes in the prologue of her book, “One of the earliest memories I have of the word ‘memsahib’ being used in common conversation is of the time I was given the role of a lady in a school play and had to dress up in my mother’s saree. Little did I know that about one and half decades later, I would take up ‘memsahibs’ as a subject of my doctoral thesis.

Looking back, I am reminded of how the word was frequently bandied about in my Bengali household while I was growing up, used in amusement for girls and ladies who put on airs or threw fits and tantrums. It was mostly tongue-in-cheek and was quite a favourite sobriquet back then, but occasionally it was used to convey genuine appreciation if a woman looked well turned out or dressed up in a ‘posh’ way. Over the years, the appellation gradually disappeared from common parlance, resurfacing occasionally in films (Bengali classics, which I acquired a taste for because of familial influence, and in mainstream Bollywood as well, although that was rare). By the time I began studying ‘memsahibs’, the term was no longer used like it was before.”

A British family in front of their home, late 1800s Wikimedia Commons

Nath goes on to admit that the “memsahibs, and their rather nebulous role in the empire, have been a significant preoccupation of feminist historians because of the steady marginalisation of women’s histories and personal narratives. I wanted to know, irrespective of the discourse, ‘could the memsahib speak?’ Were they heard? And how much weight was given to their literary or cinematic representations as opposed to their own writings?”

Here is an extract from the chapter titled ‘Missie Babas and Baba Logs’.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

One of the most poignant moments in almost every memsahib’s life in India was when she had to part with her children as they were sent to England to get their education. Parents delayed this event as much as they could, but it was necessary to send them as soon as they were old enough to travel, sometimes as early as the age of six. The parents were convinced that a few years of schooling in their motherland was guaranteed to forge the young ones’ identity as British, which was especially crucial because they had never even seen Britain before.

Moreover, proper British education was a matter of great concern because the early years that the child had spent with the ayahs and Indian servants and children had already significantly ‘Indianised’ them. Sun-burnt, dirty, brazen due to neglect by their parents, and overindulged by their ayahs, they were hardly the model of good and proper British children, and a far cry from the well-mannered and obedient Victorian schoolboys and girls trained in boarding schools back home. Thus, imparting British education was the necessary measure taken to inculcate a European world-view in them.

Frequently, parents chose not to send their children away if travelling out of India was difficult due to political turbulence, or if there was a shortage of finances, or even if they simply did not wish to part with them. In such cases, they employed European nannies and governesses and made sure the children were trained in the British manner.

India-born Anne Wright, who did not leave even after India gained independence, wrote that she had several governesses while growing up in the Raj. Her last governess was Joan Scott, who was the niece of a tea planter, and whom she described as “delightful” and “very musical” (“The Lost World of the Raj”, Ep. 1, 47.00– 49.00). Back then, British families would publish advertisements in newspapers calling for applications, and that was how Joan had come to be employed in the Wright household.

Joan, in her interview, said she had been “floundering” in the plantations for a while, and when she came across the advertisement posted by the Wright family, she was immediately interested. She quickly adapted to the needs of her employers, and Anne later recalled how Joan would always play highbrow music to them, which they loved (“The Lost World of the Raj”, Ep. 1, 49.31).

Sometimes, British children in India had Indian teachers called munshis, who taught them English and other subjects. Otherwise, they went to English-language convent schools located in nearby hill stations. These were deemed to be better alternatives to Indian schools as the missionary training by the nuns helped instil Christian values in the children. These schools also enforced British-style discipline and could supposedly help curb the ‘native’-style delinquency and waywardness in the pupils. The parents were also assured that Western education, and even European styles of extra-curricular activities such as theatre, piano lessons, glee clubs, and so on, would be provided.

However, there was a time when the convent schools in the hills were disliked because the children who studied there were mostly of mixed origins. Yet again, British families feared ‘contamination’ as their children would pick up Indian mannerisms at such establishments, including the so-called ‘chee-chee’ accent. And even though the parents partly knew that Indianisation was inevitable in the long run, they wanted their children to avoid it, or hide it underneath an aura of Britishness, as they had themselves.

When parents did send their children to Britain for their schooling, the mothers sometimes accompanied them, either to drop them off, or to be with them as they grew up. But more often than not, the memsahibs’ sense of conjugal duty won over, and they stayed back with their husbands in India or left Britain almost immediately after settling their children in. Whatever the case, if children were sent out of India it was usually several years before they got to meet their parents again, by which time they would be all grown up.

A lady with her child and servants, early 1900s Wikimedia Commons

Education was not the only reason why the parents parted with their children. Very often, concerns relating to the children’s health compelled them to remove them from India at a very tender age. If it was possible, the young mothers went back home where they could care for their children because of the help they received from their relatives. Having physicians who visited their ailing children in the comforts of their homes was a relief.

Sometimes, parents sent their children away because they wanted to give their children a stable home, unlike the situation they had in India where they might have to travel a lot, especially in cases of army families that were given frequent postings. And parents were advised not to take such matters lightly because those who did suffered in the long run. Thus, to tackle this, children were sometimes sent off to live with their grandparents who might be stationed elsewhere in India, like in the case of Lillian Ashby. However, even shuttling between their own homes and those of their grandparents could become overwhelming.

It can be said that no matter what decision was taken, it was always difficult for the children to part with their parents. The condition of the children who were sent away was as pathetic as that of their mothers who would pine for them in the faraway land of India.

The mothers indeed found it difficult to cope with the pain of separation, and their accounts of suffering are extremely evocative. Veronica Bamfield wistfully wrote about how mothers in the empire were doomed to bear the pain of living apart from their children for many years and learning about them only through their brief letters written from school. They would carry their children’s photos with them wherever they went. The verandas and large open rooms of their bungalows would echo with the calls of their children long after they left, and they would be constantly haunted by the faces of their babies.

Extracted with permission from Memsahibs: British Women in Colonial India by Ipshita Nath, published by HarperCollins India in July 2022