Humankind has managed to explore only a miniscule percentage of the deep ocean, and its ominous, watery depths have shown, time and again, their tremendous power by humbling the most advanced ships and courageous voyagers. Shipwrecks lay testimony to the sheer force of the ocean and have also long posed as sites of exploration. The OceanGate Titan submarine disaster of June 2023 has once again reminded the world that the ocean is a force to be reckoned with.

The cover of ‘Mayday! Maritime Disasters That Shook The World’ Cover illustration by Uttara Chatterjee

In his book, Mayday! Maritime Disasters That Shook The World, master mariner Captain Beetashok Chatterjee, says, “There is something infinitely sad about shipwrecks. Whether destroyed by the forces of nature or by human folly, every wreck has a story to tell.”

Thirteen such stories, dating back to the 1870s find a place in the thrilling account that is Mayday! Chronologically presented, they document vessel disasters at sea, outside of war. The accounts also highlight the impact these incidents had in spheres like environmental damage and media attention. Not merely a run down of historical incidents, Mayday! also bring into question the economic, political, and human welfare impact of these incidents, which led legislative bodies to introduce new maritime laws and strengthen existing ones in order to make the high seas safer.

Chatterjee takes seafarers and casual readers on a journey back in time to explore the causes and effects of these nautical misadventures — when and why they occurred, what we can learn from them, and could they have been avoided.

Here is an excerpt from Mayday! that documents South Korea’s ferry disaster of 2014, involving M.V. Sewol:

**************************************************************************

South Korean vessel ‘Sewol’

‘This is Situation Room.’

‘Help me! The ship seems to be sinking.’

‘A ship is sinking?’

‘We are on the way to Jeju Island. The ferry’s tilted to one side.’

‘Hold on...is this the ship you are on, or another ship next to you?’

‘The ship I am on board.’

‘What is the location of the ship?’

‘I don’t know the location.’

‘You don’t know? No GPS? What’s the name of the ship?’

‘Sewol. It’s Sewol.’

The above conversation took place between Choi Duk-ha, a High School student, and an emergency operator on the 119-Direct-Dial-Emergency-Number for South Korea at 8:52 am local time on 16 th April 2014.

It was a fine morning. Koreans were on their way to work and school. Till then the nation had no inkling of a major disaster that was taking place in its waters aboard a passenger ferry. There had been no Mayday call yet from the ship to the nearest coast radio station or to ships in the vicinity. Just a frightened schoolboy who had the presence of mind to get through to Emergency Services on his cell phone. A boy who would not live to see his parents again.

By the time the ship’s crew sent a distress call a few minutes later, M.V. Sewol was adrift, already leaning precariously 30° to port and had started to sink. There were 325 school students on board.

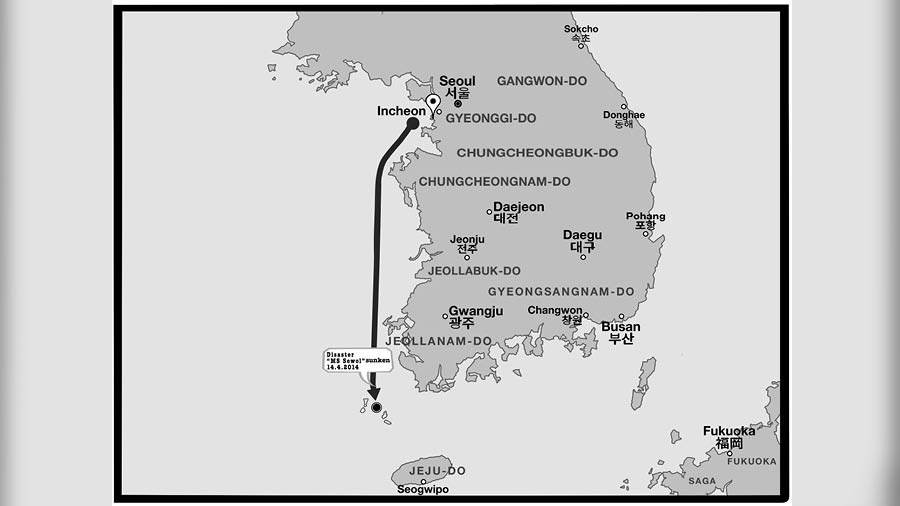

The RoPax ferry M.V. Sewol had departed from the South Korean port of Incheon the previous night at around 9 pm, carrying 443 passengers, 33 crew members, and a total of 2,142 tons of cargo, including 185 cars. Among the passengers were the aforementioned 325 students on a field trip from Danwon High School (Ansan City), eager to visit Jeju Island in the Korea Strait, a tourist destination at its prettiest in spring. The ship was commanded by 69-year-old Captain Lee Joon-seok, who had been brought in as a replacement for the regular Master.

The Sewol was no stranger to the coastal route between Incheon and Jeju. Since March 2013, she had been making three round trips per week between the two ports, each one-way voyage of 264 nautical miles (425 km) taking about 13 hours to complete. Till that disastrous day, she had made the round trip a total of 241 times.

That morning at 7:30, Third Mate Park Han-kyul and helmsman Cho Joon-ki took over the navigation watch on the bridge from the previous team. The sea was calm and the visibility good as the ship arrived at the Maenggol Channel, which lies between two groups of small islands en route.

The route taken by ‘Sewol’ and the location of the accident

Maenggol Channel has strong underwater currents, which necessitate extreme caution when steering a ship through it. The wider areas of the channel contain rock hazards and shallow patches; but these were not in the immediate vicinity of the ship’s usual path. The Sewol was following a route that was frequently used, and Third Mate Park had on multiple occasions passed through the channel on another ship. The captain was not present on the bridge when Sewol entered the channel at around 8:30 am at a high sea speed of 18 knots (33 km/hr). Breakfast was being served in the cafeteria. Some students were socializing on deck, enjoying the cool sea air.

At 8:46 am, Park ordered the helmsman to take the steering wheel and turn the ship sharply to starboard. It is not clear why she turned the vessel so sharply; it is believed that the strong current had taken the ship off course and she wanted to get the ship back on track quickly. There is no record of any fishing vessels in the immediate path of the vessel that would necessitate such a bold helm manoeuvre. That turn turned out to be fatal. The ship turned rapidly at full speed and then it was difficult to control the momentum of the turn, despite turning the wheel in the opposite direction. As the ferry turned sharply to starboard creating a semicircular arc on the water, centrifugal force caused her to tilt towards the water in the opposite direction—to port. (This is a natural phenomenon in hydrodynamics—the faster the alteration of heading, the greater the tilt of the vessel on the opposite side). The overall effect was that the ship veered about 45° to the right of her original heading, and then rotated an additional 22° on the spot for a span of 20 seconds; totally out of control.

An illustration of the ‘Sewol’ wreck

What do you think happened next? The cargo on board, stowed improperly, slid to the side the ship was tilted, causing her to tilt even further. This allowed water to flow into the ship through the side door of the cargo loading bay and the car entrance located at the stern. In just four minutes from the time the ship began the sharp turn, Sewol was leaning 30° from the vertical to her port side. The engines stopped due to the list, as they are designed to when the lub oil pumps lose suction and lubrication to the engine reduces. The ship began drifting sideways. Then the generators failed for the same reason and the lights went out. It was then that the student Choi Duk-ha made the call ashore, while the rest of the crew and

passengers were still wondering what on earth was going on.

The Sewol started to sink at around 8:49 am with the ingress of water. By this time Capt. Lee had arrived on the bridge. At 8:55 am, Sewol’s crew made their first distress call to the Vessel Traffic Service (VTS 2 ) at Jeju, their destination, but not to the nearest radio station, and asked them to notify the Korea Coast Guard (KCG) that the ferry was in danger of capsizing.

As Sewol began sinking, the ferry’s intercom system sputtered to life. ‘Do not move. Just stay where you are. It’s dangerous if you move, so just stay where you are’. The announcements were made by a communication officer, Kang Hae-seong, ordering the passengers to stay put! These continued even when water began flooding passenger compartments. Other crew members corroborated this order, instructing passengers to stay at their locations. Captain Lee also repeatedly instructed passengers to remain where they were.

*****

This excerpt, along with images, from Mayday! Maritime Disasters That Shook The World by Beetashok Chatterjee is republished with permission from Readomania Publishing. Get the book here.