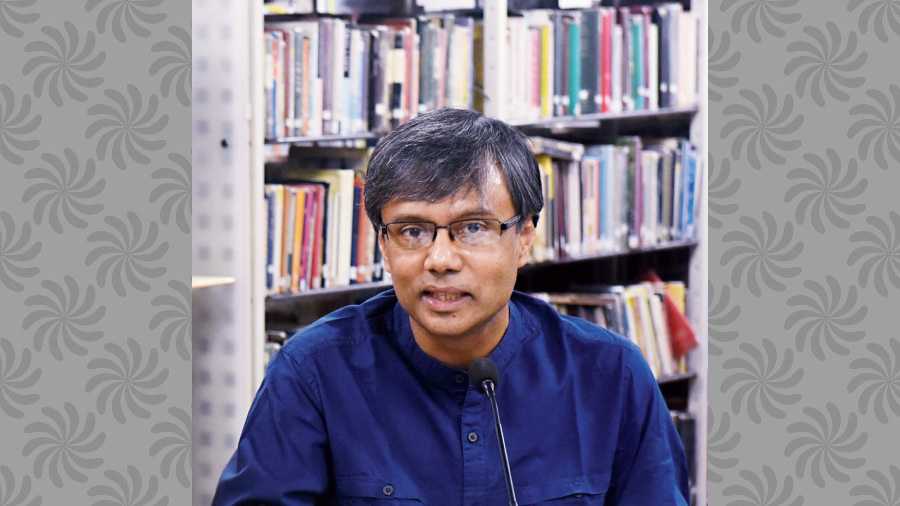

Amit Chaudhuri is on a roll. A few days ago, even as he was hitting the headlines with the most recent accomplishment of being bestowed the prestigious James Tait Black Award, for Finding the Raga, Chaudhuri must have been smiling quietly at the eyebrows he was raising with his newest novel Sojourn, which was simultaneously hitting the shelves at bookstores worldwide. Finding the Raga: An Improvisation on Indian Music (2021) won the prestigious James Tait Black Prize for Biography that is worth £10,000. Chaudhuri wrote much of this memoir during a nine-month residential fellowship in Paris. As I close the novella (Sojourn)— under 150 pages — it’s my turn to smile at how this writer and singer in the Hindustani classical tradition — whom I have studied meticulously for my doctoral research on Postcolonial South Asian writers and whose works I have subsequently taught in North American Universities — has once again landed a strategic googly on his readers with a sleight of a light hand.

What is the novel about, a colleague asks me, when I tell her that I have just finished reading Sojourn, which took five straight hours to read. It’s about a professor who goes to Berlin in 2004 on a fellowship for four months. And then, does he fall in love with someone? What is his name? I draw blanks. And my colleague seems nonplussed. The narrator, also the protagonist, is nameless and there is no plot really. The nameless protagonist meets a German woman Birgit, with whom he shares a friendship that borders on affection. That is as far as Chaudhuri will go with the distinguished alien in Berlin who seems either disinterested or not quite confident in investing any emotional content to build a relationship.

There are however, several saving graces where minimalism gives way to joie de vivre and an explosion of life — in the voluptuous imagery of food, which Chaudhuri has signposted his success in, for instance, in his memorable descriptions of Christmas fare at certain establishments in Calcutta, in his non-fiction, and in the intriguing creation of the character of the Bangladeshi gentleman Faqrul Haq, somewhat akin to Mr Pirzada, in Jhumpa Lahiri’s short story collection Interpreter of Maladies. Haq is an interesting character in Sojourn, that typical self-appointed tour guide who pops up in many metros, to ‘show’ the visitor from his homeland or close neighbour of his homeland, the best-kept secrets in a city that is not his to claim. Haq, with his slightly overbearing, I-know-everyone-and-everyone-knows-me attitude and good Samaritan air comes through as the only fleshed-out three-dimensional human being in this novel. A slightly out-of-the-box figure, who resides in the back streets of Berlin, having fled Bangladesh because of an indiscretion he committed by insulting the Prophet Mohammed in 1975, he seems harmless enough, pointing the visiting professor in the direction of South Asian restaurants, female company and stores.

Thus, Chaudhuri describes Haq and Indian food with great veracity: “As I came down the stairs, I saw a man in an ash-coloured plastic jacket smoking furiously… ‘Esho,’ he said navigating. He was shorter and older than me.” In the restaurant that the visitor is taken to, a feast is spread out before them, and Amit Chaudhuri revels in the description of the table groaning with goodies: “There was a wave of food. Chicken bhuna, dal, pilau rice, tandoori prawns.” The food, as most globe-trotting Indian readers will recognise, is the kind of fare most Indian travellers to Europe and North America and diasporic South Asians crave and find in the ubiquitous “Indian restaurants” that serve a “mother gravy” from the “imaginary homeland” for each generic curry.

What is worth noting here is how the use of the vernacular “Esho” (come) lends the text a certain “authenticity” of culture and captures the element of the familiar in an alien land. The storytelling in Sojourn, as in all his earlier fiction from A Strange and Sublime Address to Afternoon Raag and Freedom Song, is peppered with Bengali words, rhymes, doggerel verse, all of which add a palimpsest of cultural diversity and a voice that undergirds Chaudhuri’s effortless mastery over moving between English and Bengali. Perhaps what Chaudhuri deserves to be celebrated most for is his ability to forge his own voice while writing in English. As a postcolonial writer, who teaches creative writing and finds inventive ways to play with language, this rare finesse in his craft is often neglected by his supporters and detractors alike. And like Amitav Ghosh, Salman Rushdie, Homi Bhabha and the late Meenakshi Mukherjee, Chaudhuri understands the essence and indomitable presence of translation.

The word for translation in Sanskrit is anuvad, which etymologically means “saying after or again”, “repeating by way of explanation interpretation”.

It is useful to invite Mikhail Bakhtin into the discussion here since he encapsulates the core of my argument: “The author participates in the novel (he is omnipresent in it) with almost no language of his own. The language of the novel is a system of languages that linguistically, mutually and ideologically interanimates each other. It is impossible to analyse it as a singular unitary language.”

To this I would like to add that in the case of Amit Chaudhuri translation — of the imagination to the page, the oral to the written, from one language to the other — is the multi-coloured sutra (thread) that weaves the scuffed quilt that is Sojourn’s contemporary narrative. Susan Bassnett and Harish Trivedi in Post-colonial Translation state that “the underlying metaphor in the word anuvad is temporal — to repeat, to retell — rather than spatial, as in the English or Latin word ‘translation’ — to carry across”. Thus, imitation in the neo-classical sense was in India already a form of translation as being a “transcreated” repetition of something already spoken and/or written, and formed as the staple of the precolonial, colonial and postcolonial oral and literary traditions.

I suggest that Amit Chaudhuri as a member of the second generation of the card-carrying cadre of the postcolonial brigade, led by that inimitable ventriloquist Salman Rushdie, takes on language as a means to seek, explore and establish their own identity of their “morphing” nation. As Rushdie so aptly put in Imaginary Homelands (1982): “All of us share the view that we can’t simply use the language the way the British did. And that it needs remarking for our own purposes in spite of our ambiguity towards it, or because of that, perhaps, we find in that linguistic structure a reflection of other struggles… within ourselves… British Indians (Indians who write in English) are ‘translated men’.”

Rushdie opposed the view that “something gets lost in translation”, believing, like Homi Bhabha, that “something can be gained”: “This gain is mirrored in the pollinated and enriched language (and culture) that result from an act of translation — this act is not just of bearing a cross but a fertile coming together. Thus, it is not only in the case of Indo-British writers but in that of all Indian-English writers that the text that they create are translated.”

The very act of writing being of translation and chutneyfication, admittedly with ellipses, aporias, lapses, gaps, slippages and omissions, becomes a new playground for inventive wordsmiths and storytellers to usher in new ways of thinking about how to tell a story using English with a stamp of the vernacular. In his typical style, Chaudhuri in the creation of the nameless, somewhat unstable, forgetful narrator is arguably writing himself into Sojourn. Chaudhuri’s earlier novel Friend of My Youth (2017) features a writer named Amit Chaudhuri, who retraces his steps to the city of the fictional Amit Chaudhuri’s birth, Mumbai, though in real life the author was born in Calcutta. Perhaps Chaudhuri sees himself in Sojourn reflected in the visiting fellow in Berlin: “I don’t feel anxious because the streets are familiar,” soliloquises the nameless narrator. “Where I find myself is related to the return of some old memory. I don’t know what the memory is, but I recognise where I am. On the other hand, I’d say the world I belonged to, the one I came from, has little veracity anymore. It began to vanish in the Eighties and Nineties. I don’t feel lost in Berlin — here, I’m in the present.” A master of negotiations, Chaudhuri flits like a butterfly between remembering and forgetting, past and present, and straddles the translations of time and space and languages with effortless ease.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is the author of Dance of Life and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught world literature and postcolonial literature. She now lives in Calcutta and teaches English at Loreto College