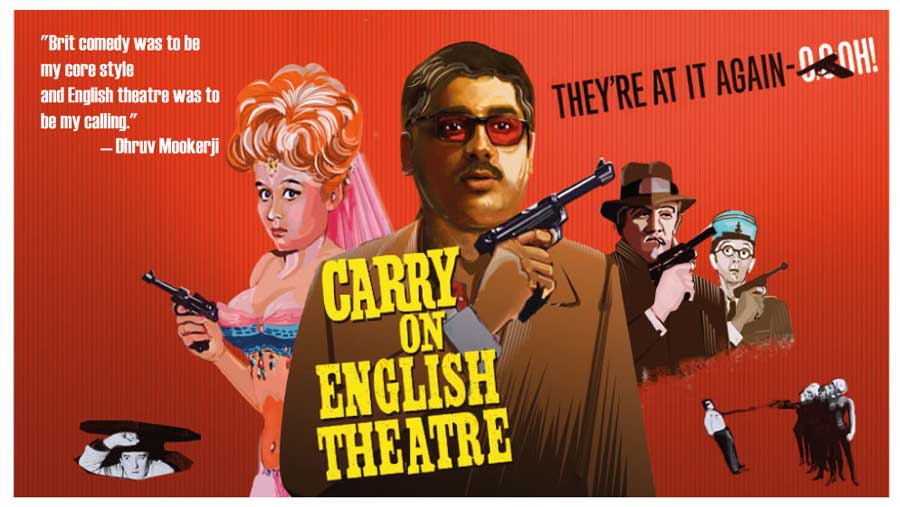

On a Sunday afternoon in 1996, I was lazing after lunch, surfing channels. TNT, which is now TCM, was about to show a black-and-white film, so I thought I’d see how it went. The film was Carry on Spying, a vintage wacky British comedy. I laughed for two hours straight, and thereon became a fan of Kenneth Williams. I began to imitate him, his mannerisms and his heavyset Received Pronunciation, watching every film in the Carry On series that featured him. Over the next few months, I’d perfected his style and projection. Unknowingly, I had started on the road as an actor. Brit comedy was to be my core style and English theatre was to be my calling.

The fact that I could take what was effectively an idle pastime and make the transition onto the public stage is testament to the English theatre culture in Kolkata. It is, without doubt, a niche culture with a very limited audience base, but it’s there for those who want to chisel their art in it. I’d had some experience of it as a young audience member. My oldest memories are of watching Suhel Seth in Don’t Drink the Water, Cedric Spanos and Pradip Mitra in Habeas Corpus and Proscenium’s production of A Streetcar Named Desire

Many contrasting styles

English theatre at the turn of the century was safely in the hands of veterans who’d been performing for years – groups like Spotlight, Stagecraft, Proscenium and The Red Curtain (which was soon to return to the city after delighting audiences in the ’70s and ’80s). Theatrecian was formed in 2001 with a specific purpose — to induct a whole new generation into the world of Kolkata English theatre. Tathagata Chowdhury, the founder, had the simplest philosophy — if you had a spark of interest in theatre, you were in. It was here that I developed sensibilities beyond the classic English theatre style. And it’s been a joy working with people with so many contrasting styles, all of us feeding off each other.

Deborshi Barat (left), Dhruv Mookerji (centre) and Tathagata Chowdhury during the technical rehearsal of John Osbourne’s ‘Look Back in Anger’, Gyan Manch, 2013

English theatre has widened its scope in the years since I sat gaping at the stage as a kid. The old days were more about approaching theatre in the classic way — performing full-length English plays, creating picture-perfect sets, driven by performers with mastery over spoken English, handling English and American plays with equal ease. Shakespeare, Oscar Wilde, Neil Simon, Agatha Christie and other classics were the staple.

Theatrecian’s Indian adaptation of Neil Simon’s ‘Rumours’, performed in 2009

Today, groups are more experimental, often eschewing the full-length format for shorter plays, experimenting with form, breaking language barriers, adapting to the Indian context. Most significantly, the past two decades have seen a massive surge in original playwriting, with groups like Tin Can, MAD and Theatrecian itself churning out original content.

The legacy of our English theatre as we know it, dates back to the ’60s and ’70s, where the likes of the Bhagat brothers won hearts and fans. Zarine Chaudhuri has balanced brilliant performances in the classic mould alongside her development of theatre as an inclusive form, with The Action Players. Phyllis Bose, the late Rohit Pombra and Katy Lai Roy have given the city some of its most memorable productions. Katy Lai Roy continues to create magic with The Red Curtain, while simultaneously honing new talent with terrific school productions.

A close-knit world

The world of English theatre here has been, for the most part, a close-knit world. If I had to make an estimate, I’d say that, until the previous decade, the number of people acting on the English theatre stage would not have exceeded 100 in the city. With the evolution of form, languages and spaces, more and more people are drawn to it, and newer, younger audiences are flocking to the theatres. English Theatre, as a term itself, no more refers to the world of performance exclusively in English. English is just one of the languages in a group’s repertoire. I have helped create a production called The Comedy Kitchen, which is an evening of short comedies many have been adapted from British comic sketches, and many are original pieces. The plays are a mix of English, Bangla and Hindi, and that’s as reflective of the modern age of English theatre as can be.

‘Mr. Kashmakash’, part of the Comedy Kitchen series, is a Hindi adaptation of the ‘Beekeeping’ sketch by Cleese and Atkinson

There has been a tendency, over the years, to scoff at English theatre as a world of artistes with a colonial hangover, performing for audiences with a colonial hangover. While the statement is sweeping, there is some truth to it. We’ve often sought out our comfort zone in the Wildean style of charming English. Though there have been plenty of productions over the years where actors have relied on their standard spoken English, the sensibilities have been unmistakably Western.

‘12 Angry Jurors’, an adaptation of a 1954 play, performed by Theatrecian in Gyan Manch, 2012

On a personal note, I deeply regret never having been equipped for Bangla theatre, and missing out on the experience completely. While most of the theatre performers I know are far more comfortable in speaking Bangla, their performances have also been almost exclusively for the English theatre audience. The niche swells, but only just so.

In 2006, I acted in a play called Raisin in the Sun, where I played a black American. We all had to develop strong Southern Black accents, and it took us a massive effort to get there. I remember people grumbling that it was ridiculous to present a play in a spoken style that was utterly foreign to us. And yet this complaint has hardly ever arisen going all-Brit on the stage.

Colonial hangover it is, then!

(L-R) Zara Sengupta, Dhruv Mookerji (as Tony Wendice) and Zahid Hossain on the sets of ‘Dial M for Murder’ — Theatrecian’s 2015 adaptation of a British play made famous by Alfred Hitchcock for the silver screen

Dhruv Mookerji is a creative director with Ogilvy. He is a founder-member of Theatrecian and has performed for 15+ years as an actor onstage and in movies, television and ad films. He’s also a quizmaster and content developer, having worked on ‘Kaun Banega Crorepati’, and being Content Head for Classmate Spell Bee over the past few years