My first memory of woollen clothes was not of the ones I wore. It was those that a Krishnanagar clay doll was bundled in. A fluffy wool cap in pink and a front-open cardigan were draped on the figurine of an adolescent boy. The clothes were so real that each puff of the wool yarn was crossed by a memory of clouds. A fixture in our glass showcase, I had named the doll Tukai. He was my playmate through long summer vacations, as I sat by the window watching the birds chase the sun.

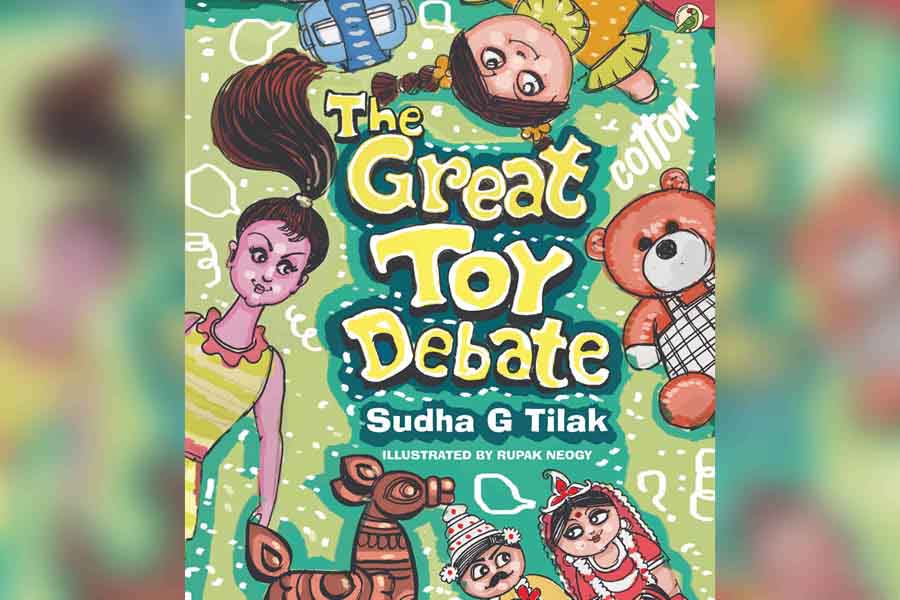

This lost world came back to me with The Great Toy Debate, published by Perky Parrot, a new imprint by Niyogi Books for children and young adults. In the book, journalist Sudha G. Tilak conjures up a universe of toys, playful and inviting, yet not bereft of important but uncomfortable truths. She starts the book — meant for children six years or older — by introducing the toys, vivid and whimsical, with links to the rich and diverse Indian toymaking tradition.

The toys are being carried by their creators, Badal Mondol and Jhumur, to the Durga Puja Shilpi Mela in Salt Lake. They are animated with the memories of cultures and communities, rituals and craft traditions. “India is one of the few countries in the world today with a living tradition of folk toys,” commented Prof. Sudarshan Khanna, former head of the Toy Innovation Centre at the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, in his seminal work, Dynamic Folk Toys. He has also chronicled the keen inventiveness of Indian toymakers in recycling materials: “Toymakers who live in cities and industrial areas now make use of materials that have been used before. This recycling includes newspaper, discarded cartons, boxes, tins, metal scraps, and other odds and ends.”

It is this idea of sustainability that lies at the core of Tilak’s book. The author places two categories of toys in direct confrontation — a face-off as if — to underline and illuminate the great crisis around unsustainable overconsumption in the modern world. The first category, tracing its ancestry to Indian craft communities, includes a pair of shola pith wedding dolls, a cloth doll, a wooden rocking horse, wooden jhum-jhumi and other toys. The second group, a motley crowd of assembly line plastic playthings, reek of a society drugged with consumerism and economic materialism, teetering on the precipice of multiple ecological disasters. After stating the obvious contrasts, Tilak goes about complicating the narrative further.

Nature of the relationship between toys and children

Toys have a special place in childhood. ‘Toys indicate the capacity of humans to create a world they are familiar with,’ says Sudha G. Tilak

Despite the gloss and glitter, the plastic toys have no overarching story arc in their lives. They live a preordained existence, their destinies printed out by corporate bosses so as not to destabilise a profitable annual report. Most importantly, the relationship between these toys and children is tenuous at best, mediated by an army of marketing professionals and drowned out in a blitzkrieg of product advertising.

Toys have a special place in childhood. “Toys indicate the capacity of humans to create a world they are familiar with,” says Tilak. They could be seen as metaphors for curiosity and freedom, imagination and discovery. Handmade Indian toys, with their context of stories — layered and nuanced — allow children to access and navigate a world bereft of commercial concerns but one that sparks wonder.

In Tilak’s world, all the toys (both Indian and generic) have been given portraits that are alive with a wealth of detail. They help anchor the cultural conversation around playthings. Gudiya is an Indian rag doll, dressed in a “long cotton skirt with a red floral print and a green blouse. Her midriff and hands and face were made of pale cloth.” The shola pith wedding dolls have “elegant faces, made of the milky stem of the shola plant”. There’s even a terracotta horse from Bankura who is “breakable and made of earth” but also “on the logo of the Central Cottage Industries Emporium of India”. The distinctive one-of-a-kind dolls pave the way for Tilak to go back in time: “I only had dolls that my mother crafted at home. I also had a lacquer and wood kitchen set, indigenous to the town of Tamil Nadu I came from. That was all. Today parents are tripping over their children’s toys as they have too many.”

While the handcrafted dolls in the book speak to the young reader through a map of their historical landscapes, the mass-produced toys place their arguments in an ecosystem of globalisation, climate crisis and a binge consumption of media and marketed products. The rebuke of one of the template toys is a commentary on the broken idea of spontaneous fun. “I have kids who are my fans all over the planet. You can watch me be a star on TV and in games too. Beat that, rag doll,” gloats Penn, a plastic toy.

How to keep rich traditions alive

Indeed, the world is writing an elegy to both the handcrafted doll and its maker. To keep the traditional toy culture alive, painful conversations, as those voiced in the book, need to act as constant reminders of the loss of a way of life. However, awareness about rich but fading artistic practices also have the power to work miracles. “There has been a surge in popularity of the dolls from Bengal that we sell. In the six years of our online presence, this is the first time that we will be opening a brick-and-mortar store in January 2024,” says Arijit Sen, an employee of the Kolkata-based online retail venture, The Bengal Store. It sells clay dolls from Krishnanagar, Mojilpur in the South 24-Parganas, shellac dolls from Purba Midnapore district, Shoshthi dolls from Kunoor town in North Dinajpur, Queen doll or ‘Rani Putul’ of Howrah and many more. “The idea is not just sales, but taking Bengal’s obscure and labour-intensive craft traditions to the world,” says Sen.

Queen doll or ‘Rani Putul’ of Howrah The Bengal Store

Truly, the story of the crafts people is intertwined with the story of reimagining childhood. A plaything, that is connected to the hand, to the land and its context, offers children the scope to conjure up new worlds with meanings and possibilities. Those worlds are not entirely stripped of character, like the carefully rehearsed interactions between global plastic toy franchises. Tilak’s book underscores this tension between the organic and the imposed, letting it inform the worldview of adults, often in a tearing hurry to prepare their children for the marketplace.

Rupak Neogy’s illustrations, characterised by a bold colour palette, conveys the vibrance of folk toys with regional inflections. Local textiles, cityscapes and infrastructure are etched in assured strokes, offering Tilak’s story a conducive climate to thrive. The details of the art work (expressions and body types) also speak of a strong individual voice. They are much like the dolls in the book, who are at first, ignorant and fearful of their shiny Western counterparts, but later regain pride in their diversity. It offers hope that our homegrown toys can hold their own in a world of homogeneity and are not hurtling towards obsolescence anytime soon.