Eidi is a cash gift by family or social elders to children on the big day.

It is an intimate practice, probably inspired by the kings of old who disbursed vast sums or liberated prisoners on Eid. They could well have been inspired by stories of Bade Miya in the skies rewarding supplicants after 30 days of fasting.

This has, like other things, trickled down as part of a rich Indian tradition. In Eidgah, Munshi Premchand wrote emotionally about an orphan getting an Eidi from his old grandmother. She expects that he will go out to buy sweets. He goes out alright, but to buy her a pair of tongs instead to save her fingers from singeing while preparing rotis. Just the kind of reference to enhance the brand for Eidi.

In the innocence of the past, this tradition was comfortably sustained because at the most, one was expected to give out loose change. In the Seventies, a Rs 2 Eidi was standard; if you got Rs 5, you immediately upgraded the benefactor a couple of notches in your credit rating.

The smallness of the amount retained the intimacy. You went out of home on Eid morning in sparkling clothes after having been instructed by the parents to do salaam by touching your right eye, then the left eye and finally a kiss on the back of the other person’s palm. The person you were doing it to either squeezed your chin or cheek, depending on the flab, rubbed a hand on your head or kissed your forehead depending on how you looked, how you were related to the person or how many days you had fasted.

These elders were canny; they knew that what worked for the others would be wasted on the child, so they offered sev ka laddoos, sheer-khurma, cashew nuts and badaam only out of a sense of formality, knowing that these were not ways to win a child’s everlasting fandom. You offered something else; you offered money. The money represented empowerment; in a social grid where one was expected to ask one’s parents for everything — “What should I wear today?” and “Whose house should I visit first on Eid?” — that Rs 2 was an open general licence. One could spend without seeking parental permission; one could disburse as one wished; one could be the master of one’s own destiny; one could become what is now celebrated within the economic broadsweep… a consumer.

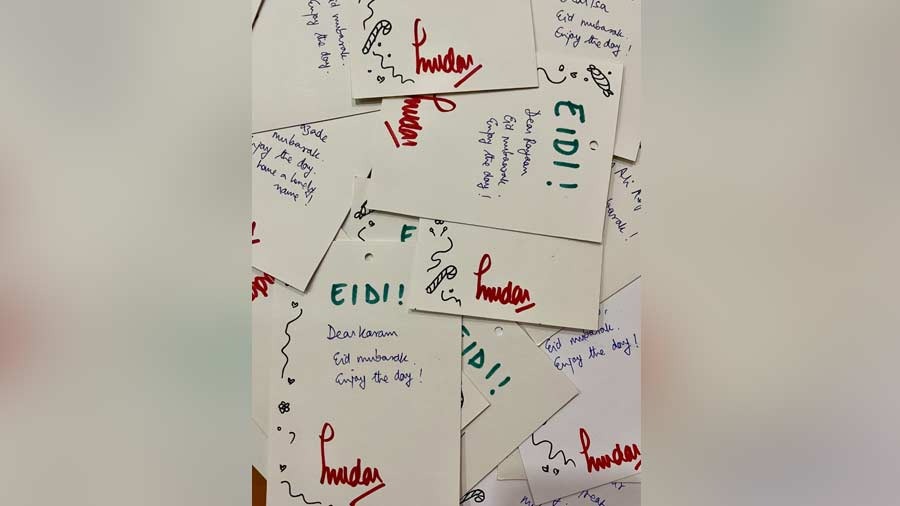

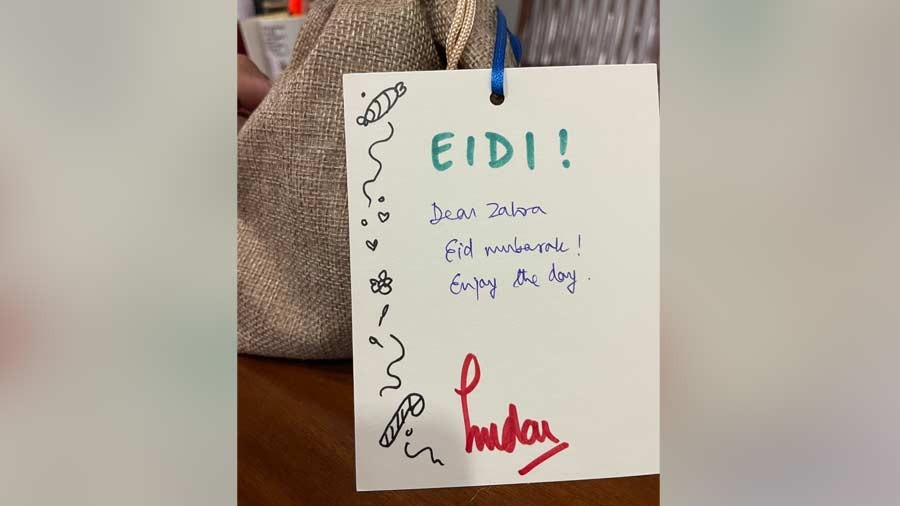

Mudar Patherya wrote a card for each Eidi bag

Money that mattered

That Rs 2 Eidi was also my first introduction to corruption. Having licked a tincture of blood, my mind would appraise prospective homes: “That uncle never gives money, only gives unrefrigerated Thums Up”, or “That aunty gave torn currency last year that the paanwala refused to accept”. My order of visits would be sequenced as per homes that generated good, clean and sizable currency. The morning’s majoori would inevitably pool around Rs 13 to Rs 17 for labours based on the declining tenure at each home, only covered by increased ‘turns’.

The money was never frittered. In my seemingly inconsequential but purpose-driven existence, the cash would be ‘invested’: invested in buying Sportsweek for 50p for some weeks, creating a war chest to buy Sportsweek’s Cricket Quarterly and waiting for the day one would be able to finally land the biggest catch — a copy of The Cricketer International.

But only until the time facial hair appeared. When that catastrophic biological transition transpired, the Eidi bonus would be replaced by the lady of the house pushing the crystal glass with laddoos with the words: “Lay ni? Sarmaaich sukaam?” (Why don’t you take? Why are you hesitant?)

Eidi reinvented

This Eidi thing would have been driven out of my consciousness had it not been for something a couple of years ago. My 76-year-old father-in-law, Ram Pratap, demanded Eidi in the thick of the 2020 pandemic wave. Caught off guard, I turned up the following evening with an envelope for his grandson — my wife’s nephew — instead.

That one line — “Beta, Eidi kahaan hai?” — seeded an idea. Nothing happened for months, until a couple of weeks ago I resolved to resume this dying practice (few people give Eidi these days following the increasing practice of eight-year-olds examining a meagre Rs 50 note upside down to check if there are no additional notes that might be stuck and could have escaped the recipient’s attention, like giving a child at a traffic signal a Re 1 coin, if you know what I mean).

The bags had Alpenliebe candies, stray Rs 2 coins, some currency and a card secured by a ribbon

Last evening, I sent out 21 Eidi bags (jute bags from Lata Bajoria) to kids across communities. I filled each bag with Alpenliebe candies. Stray Rs 2 coins. And some currency. I wrote a card secured by a green ribbon.

A few children sent me voice messages on WhatsApp (every third word prompted by an overseeing mother). Some parents sent pictures of their children with the bags. This was an adapted tradition: No child came home; no one did salaam: I didn’t go to any of their homes; we may never meet.

But each year, I promise to send Eidi bags filled with even more sweets, a few stupid plastic whistles that create a shrilled racket and a few other things that make no sense but delight children no end. Maybe I will widen the circle to cover even more children. And hopefully they will look forward to Eid because there is some character somewhere taking time off to remember that they exist.

And yes, I didn’t put Rs 5 in each bag (adjusted for inflation); I slipped in Rs 500. The giver was as happy with the giving as, possibly, the children on Zakaria Street, Chittaranjan Avenue, East Topsia Road, Khairu Place, Satish Mukherjee and Southern Avenue were receiving.

There is no shortage of wonders in the world; only an absence of wonder. Maybe that Eidi bag will correct the imbalance.