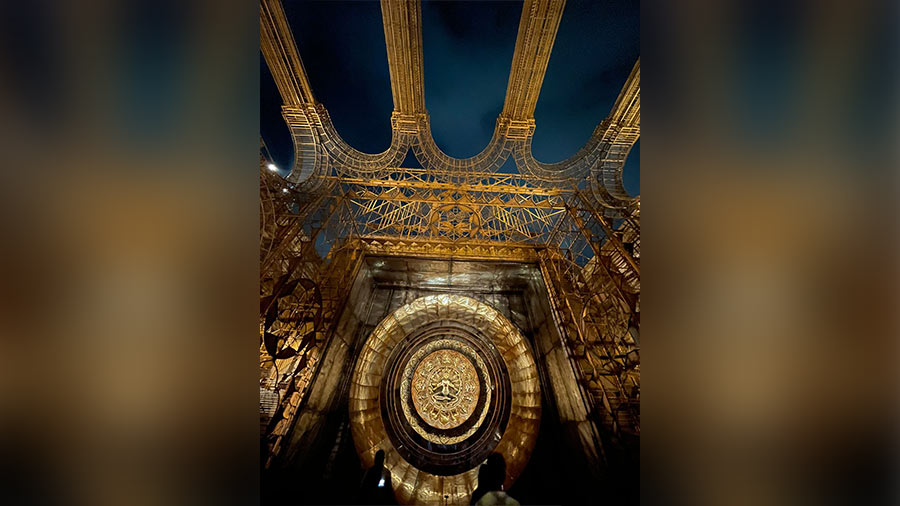

During the Diwalis of Mission Row…

We Patheryas played half-cock, like in cricket; neither aggressively front foot and neither back foot defensive, so what you had was a typically Bohra response — somewhere in the middle, but adequate enough for us conversative Muslims to get a sparkle in our eyes when we entered the week of the most awaited festival of the year. The Diwali raunaq came from a lighted evening as opposed to Eid ul Fitr, which was largely a morning relief without sound or light spectacles. Besides, Diwali arrived at a specific time of the year, when our part of the Earth was beginning to cool, you could feel a morning nip, afternoons would turn mellow and a Kolkata maghrib (sunset) around 5.15pm enhanced cosiness and a feeling that all was well with the world.

We curated a customised Dawoodi Bohra response to Diwali: we would place equidistant diyas on our verandah to enhance “ghar ni raunaq” (parental description) but would express a polite inability to participate in a neighbour’s puja where we had been invited (later they got the message and stopped asking). We would buy a bag of crackers from Bandookgalli (majority phooskis, which was our code for duds) but desist from painting an alpona on our doorstep (considered too Hindu for Quran-quoting parents). We would begin the new Samvat or financial year with a Bismillah (In the name of Allah) inscribed by the local head priest at an auspiciously appointed time (usually 6.52pm) at the head of the first page of the accounts book (described by that elegant word alaamat), but there would be no garlanded Lakshmi idol on the premises. It is a commentary on a secular India that even though we as a community have often been accused as being clannish and insular, we infused the Islamic into an intrinsically Hindu festival. We didn’t poop the party and stood out; we blended in.

Diyas on windowsills on Diwali night Wikimedia Commons

'Atmosphere people' in happiness circle

We (as in the male members of the Patherya family) would be invited by the affluent of the Bohra community to attend the moorat (Gujarati-ised version of the word mahurat) at their Clive Street shops, which was nothing more than the ritual of being mute witnesses to the Bismillah being written into the ledgers (described by that terrible sounding word chopdaa). We were supposed to wear our Eid best following the host’s prompting (“Saanjhey moorat ma aavjo-ni”) and go off to the offices of community elders, traders and businessmen. There were two ways of looking at this: it was the host’s way of widening the happiness circle with an invitation that sent out a message that we mattered (however nominally); the other way to look at it is that an audience was required to make the host’s shop appear adequately peopled (succinctly described by a word we plucked out of the Gujarati called vasti). After years of being available ‘atmosphere people’ (Hollywood’s term for extras), my mother dropped the hint that perhaps it would be best if the young man of the family (turned out to be me) would need to go ahead and set up an office with a desk and some peons so that we could, in turn, invite others to become our ‘atmosphere people’.

This tradition encountered an existential crisis in the later years; the start of the financial year in India was changed to April 1. The institution of the alaamat continues and ledgers placed one after the other in the local Anjuman office for the head priest to calligraph 873 Bismillahs in succession, but over the years this has become, without the magical Diwali context, a series of clerical entries. The night provided a sense of wonder and ceremony; without the lights, crackers, new clothes, kajoo-kismis receptacles and colas being proffered liberally, the day could be like any other. Worse, April 1 could come bang in the middle of Ramzan, raising the possibility of grim shop owners filing into the Anjuman office, collecting their chopdaas and leaving.

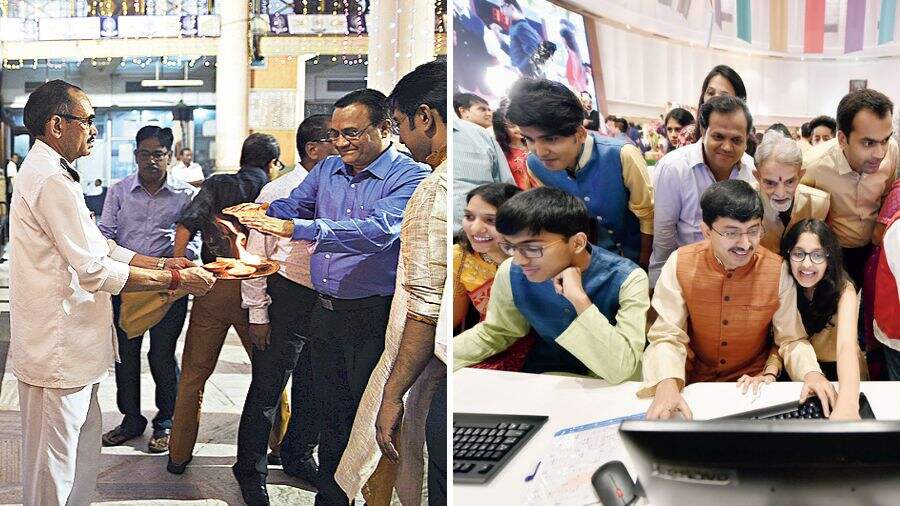

With the alaamat shifting seasons, the last ‘ceremonial’ dimension left for a Bohra like me is the moorat trading on the stock exchange. There was a time when Paresh Bakhda and I would troop to Lyons Range during the outcry trading days for the moorat ka sauda (which we naively believed should end in a profit, however minor, so that successive trades through the year would be similarly profitable).

Celebrations at Calcutta Stock Exchange and (right) brokers with their families during Samvat or Muhurat trading in Bombay Stock Exchange TT Archives

Moorat raunaq

What made the moorat trading special was the anticipation that everyone would turn a buyer (based on my expressed notion). This would strengthen the trading mood (the word we used was ‘sentiment’), prices would rise and everyone would go home happy. I mean which wretched soul would want to short Hind Motor or Assam Frontier or Tata Tea on such an auspicious evening? It is this expectation of bullishness that enhanced a latent ‘look forward to’ in our small lives; we expected that listed companies would perform better in the new Samvat; we expected that we would all make more money; we expected to wake up one day and expect the world to be in a sweet spot.

The one improvement that we did perceive immediately was in the way everyone materialised at the stock exchange that evening. In the Kolkata of 40 years ago, there used to be a raunaq in the moorat trading. The broker who would have been in unironed cotton dhoti-kurta during the day would have graduated to creased silk by the evening; the sub-broker who did usual sprints between the trading ring and the broker’s ground floor office across Lyons Range would be in either kurta-pyjama or dhoti-kurta; the trader who turned up in bush shirt-trousers on most days of the year would now be unrecognisable in the traditional. For the first few minutes, you could not bring yourself to start with the transactional “Ashokbhai, bajaar ni rukh?” (Ashokbhai, what is the market direction?) Even though you would have met him just four hours earlier, the tone of engagement would be the more sociable “Kem chho Ashokbhai? Diwali Mubarak! (Hind) Motor shu laageych? Moorat ma hajaar pot-tay karjo please.” (How are you Ashokbhai? Happy Diwali! What do you think of Hind Motors? Can you buy me 1000 shares in moorat trading?)

I have seen wondrous Kolkata sights across the decades but to have seen some of the older Marwari brokers in their black convex caps and silks on the trading floor is something I will cherish of the Kolkata Diwali; in a later age, they would have been ‘selfied’ and it is a tragedy that the dhoti-kurta and traditional headgear have been mothballed in the Diwali context, partly because — with systems turning electronic — there is no point in being all dressed up with nowhere to go.

The 30-apartment Premier House on Ganesh Chandra Avenue (Mission Row)

Dus hazaar ki lari

The one Diwali dimension that remained democratic was in the bursting of crackers. While making a mess of myself in Holi, I would be mildly provoked by the building’s durwans (“Musalmaan ho kar Holi khelte hain?”) but nobody raised an eyebrow when I banded the neighbourhood gang to rise at 5am to compete — all the Mission Row buildings on our side of the road versus all those on the other side of the road — accompanied by audible commentary by yours truly, perched strategically on an Ambassador bonnet: “Ab aa rahi maidan-e-jung me Saha Court se Madam Rohini. Unkay haath me ek jalti hui phool-jhari. Bhaiyyo-beheno (Ameen Sayani style) ab dekhna hai ke is phool-jhari se kaun si aag lagegi… rocket me ya chocolate bomb…”

The high point of our Diwali would transpire late in the Diwali evening when the retail ammunition of the neighbourhood had been consumed. Just when a lull would have begun to descend would emerge the big guns of Mission Row: the Kapoors of Minerva House. There was a cultivated mystique about the Kapoors; they were the tony aloof kids of the neighbourhood who celebrated festivals on a scale like their Chembur (Mumbai) namesakes. There would be an aura about them; fittingly, they would descend with their “dus hazaar ki lari” (string of ten thousand crackers) around midnight. This would be our Diwali high noon (!); the festival could not be considered consummated in Mission Row without the ceremonial laying out of an interminable sequence that would provoke a neighbourhood hush (“Jaldia aao! Shuru ho raha hain!”). Bedroom room lights would start popping across the neighbourhood; heads would crane out of windows and verandahs; durwans would mill hands-crossed out of gates; for the next seven minutes no one on Mission Row would speak — or be able to hear anything else either.

Shutterstock

Days innocent of social courtesy

In the Diwalis of my childhood, we created a Respect Index. The studs of the neighbourhood were not necessarily the ones who swerved their bikes helmetless street to street with deliberately punctured silencers; the studs were those who held a rocket with two fingers (never bottle) while it was being lit; they were those who retained the red pencil-shaped bomb for a few seconds in their hand flicked (never threw) from the verandah only when confident it would burst at the right moment before it touched the pavement; they were neighbourhood girls who, when they replicated this flick, generated multi-gender respect and a nodding of heads (local Morse for ‘respect’).

Those were days innocent of social courtesy as we incinerated chocolate bombs on our building staircases to measure resonance; the ‘rassi’ generated enough white smoke to turn the Marwari aunty’s dinner potentially carcinogenic; we burnt ‘saanp’ on clean mosaic floors, creating hideously black spots that warranted three months of ‘potaa’; we defined success by a misdirected rocket that veered into a neighbourhood resident’s dining room as the residents leapt for cover (following which we dissolved into the evening, only to emerge 30 minutes later with the alibi of “Uncle, hum log to abhi-abhi aaya…”).

The Diwalis of today are spent farming hundreds of Shubh Deepavali videos on WhatsApp, spending office hours cleaning the smartphone of downloaded junk, keeping windows closed to shut smoke out, being intimidated by police notices inside our building forbidding anyone from bursting smoke-generating crackers; trading moorat equities through online convenience without a human interface while sitting in one’s banyan-pyjama and mistaking a chocolate bomb for something you put inside the fridge and cheat on while on a diet.