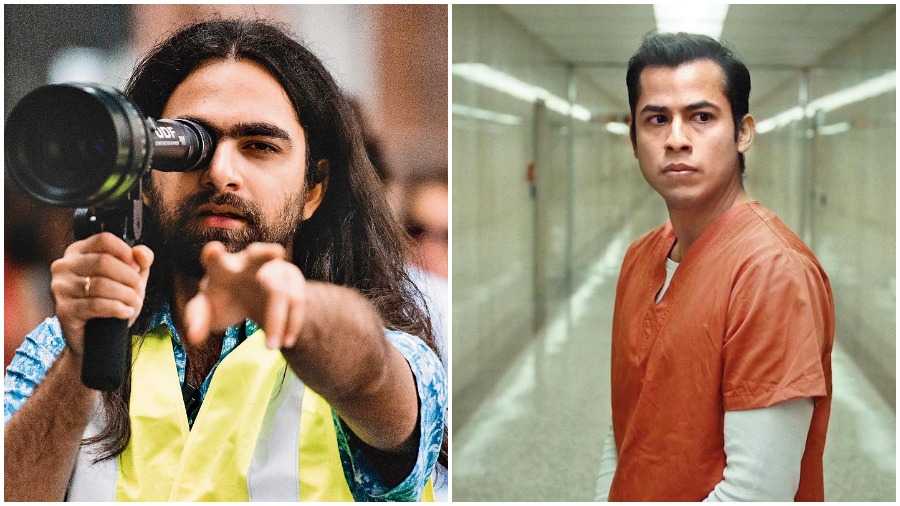

Please Hold, a 19-minute sci-fi short about a young man’s life being derailed as he finds himself at the mercy of automated “justice”, is in the running for an Academy Award in the category of Best Live Action Short Film. Please Hold has been shot by ace cinematographer Farhad Ahmed Dehlvi, who has films like four-time Oscar winner Life of Pi, among others, to his credit. The Telegraph caught up with Dehlvi, who was born and raised in Delhi, for a chat on Please Hold, his craft and more.

Congratulations for Please Hold’s Oscar nomination. You are not new to awards and accolades, but does the fact that this is an Academy Award nomination make it more special?

It is special because of the history and prestige associated with the Oscars, and also the fact that ours is a Latino story, an outsider’s story about the privatised prison system in America and the degree of control technology can hold over our lives. I’m glad to see the Academy recognising this kind of work.

You can’t think about the outcome, awards or accolades while making a film... each film is a leap of faith. You hope that you do justice to the story and that it will have an impact on the audience. I’m happy that the film moved members of the Academy enough to vote in our favour. The nomination is a real honour and we have our fingers crossed for March 27. I hope people watch our film and hopefully engage in the ongoing conversations about the subject!

What makes Please Hold different from the other prestigious projects that you have shot?

One of the things I’m most proud of in Please Hold is the tone we struck, both visually, and in how the story plays out. It is a dark comedy that gets increasingly absurd and Kafkaesque. I drew inspiration from the portraits of Lucien Freud and the films Minority Report and Trainspotting. By the end of the film, I hope that you’re left with a pit in your stomach because of how closely this ‘science fiction’ parallels our reality.

One of the challenges of a short is that there isn’t much screen time to set up the world, to build context for the story. As a cinematographer, I search for ways to do this as simply and effectively as possible. With Please Hold, we found an elegant solution — to have a mural on the wall behind the character in the opening scene. The mural, which depicts a fire-breathing, rampaging robot with Lilliputian humans trying to control it, tells us so much about the world and setting of the film.

Our resources were very limited and we benefited from a lot of goodwill from within both the industry and the community. In particular, Panavision, with whom I’ve worked for many years, supported the project with a camera package and our choice of ‘Panavision Ultra Speed’ lenses to tell this story.

Your work, both as cinematographer and film-maker, has been eclectic. What would you pick as the biggest turning points in your career?

After finishing grad school at the American Film Institute in Los Angeles, I spent a few years travelling across the US working on documentary projects. My time on the road, especially in the rural south, was a real schooling in the stratifications and power structures of American society, and triggered a process of reflection that has given me a new perspective on my own culture and my childhood in India. Looking back, I’d have to say the biggest turning points have been the collaborators I met, some of whom have become like family now. They’ve taken me on journeys I could never have dreamed of, tasking me to lend images to their stories.

A large part of your work focuses on making the universal personal. What is the key to achieving that?

I strongly believe that beyond entertaining or diverting us, inclusive cinema has the power to bridge cultural divides, to help us recognise our own pathos as we see it in others. I acknowledge the dignity of those that stand in front of my lens, I accept their nuance and individuality, and treat each one as the hero of their own story.

I don’t use the camera as a shield or a dividing line on set. I recognise the intimacy between subject and cinematographer and step out from behind the lens and acknowledge that the actors are more than icons or subjects and they are living, breathing people. Of course you do this while respecting the actors’ space and their own process.

My hope is that when the credits roll at the end of a film, the audience has a moment, however brief or subliminal, where they see their own circumstances in a different light and through the shared experience of the film, perhaps feel more closely connected to the person in the next seat.

I draw a lot of influence from the world outside of film. In recent years I have been studying folk crafts, both across India and the ‘Mingei’ movement in Japan. In particular, I’ve been looking at the use of pattern, and how a motif evolves over time. The timeless quality of traditional patterns is something I want to infuse into my work. The writing of Soetsu Yanagi has had a big impact on me. Also the artist Agnes Martin and photographer Sebastiao Salgado.

Your work is distinguished by its simplicity. In this age of visual effects and tech tools, how do you manage to retain that?

My first priority is always to serve the story. Everything I do, my creative choices, my methodology, the technical decisions are all in service of translating the essence of the written word into images that can connect the audience with our characters. I spend a lot of time with the material in pre-production to ensure that I’m prepared to actively create the visuals while ensuring that the mechanistic aspects of our work don’t disrupt the flow of the performances. This often involves months of work together with the director and production designer where we break down the film and build the visual language piece by piece, talking about light, colour, movement, and also how we can best use the set design and blocking to support our storytelling.

I aim to create a safe and flexible space for the actors and director to work in. I try to keep the equipment and crew outside the set as much as possible, and once we are into a scene, be ready to capture the performances that unfold.

Of course, there are times when a scene calls for a more technical approach, whether it is a precisely constructed camera movement or a particular lighting technique. These moments can feel more mechanical on set, but you have to trust the medium, trust the craft, and if you’re in service of the story, then the final scene, when it plays on screen, will look effortless and truly emotional. The audience will be transported into the movie. These moments are far more effective when you’ve built them into the grammar of the visual storytelling, contrasted them against the quiet moments in the film. It is like a piece of music — you need the pianissimo to feel the effect of the big crescendos. So I wouldn’t say that I eschew any particular tech tools or follow a dogmatic approach of simplicity. I’m always in service of each moment in the story.

Growing up in Delhi, was there an epiphanic moment that made you want to pursue this as both career and passion?

There are many! With both parents working in the industry, I was introduced to films at an early age One moment comes to mind — my first memory looking through the viewfinder of a camera. A visiting photographer, a friend of my parents, allowed me to look through his camera. It was a Hasselblad, a medium-format still camera, and had a viewfinder that showed you a reversed image that was very crisp, almost like a 3D projection. I fell in love with the way this camera’s viewfinder made the everyday image of our garden look magical, more real than reality, like a glimmering 3D projection. I was quite young at the time, and was enchanted with this ‘black box’ that could literally turn the world inside out. Of course now I understand the physics behind it.

I love the mechanical, the optical, the photochemical side of film-making, and I think this goes all the way back to my earliest experiences with a still camera. Getting some black-and-white film out of my father’s ‘stash’ in the fridge, watching him load it into the camera, going out and pressing the shutter with a child’s curiosity and then watching the images develop in a darkroom tray. This process has always been magical for me — a kind of alchemy, pulling images from a place that lies even beyond my imagination. I try and bring that curiosity to my work every day.

Is directing a natural extension of your work in cinematography?

I have always been narratively driven in my work, and having been in the director’s chair has made me a more sensitive and thoughtful cinematographer. I can see things with a broader perspective, am better able to shoot “for the edit” and am more closely in tune with the overall rhythm of the film. I think each informs the other, but I don’t see directing as an extension of cinematography.

I’d like to explore directing, particularly in episodic fiction while continuing to work as a cinematographer. There are several cinematographers who are balancing directing and shooting. Andrij Parekh did this with HBO’s Succession a few years ago, and Dana Gonzales on Fargo.