For chef Koyel Roy Nandy of Kolkata’s Sienna Cafe and Store, Sankranti meant making pithe with the women of the household, where everyone sat together kneading and moulding the pithe while sharing laughs and taking digs at each other.

“I lived in a joint family, so I’m blessed to have grown up with the nurturing love of many women. Sitting together, making choshi for the choshi pithe, is a much loved memory I have from Poush Sankranti at home,” said the 31-year-old chef when My Kolkata spoke to her about Sankranti special food in Bengal.

The many traditions of Sankranti

In Bengal, Poush Sankranti or Makar Sankranti, also called Poush Parbon, is all about the newly harvested rice or nabanna. For someone who carries the traditions of Bengali cuisine close to her heart, the various ways in which this new harvest is cherished makes for an interesting study.

“There are many little traditions of Sankranti, which are so specific to households and regions in Bengal — something I’ve observed during bari’r Durga Puja as well.” Her own family roots are in Purba Banga (Bangladesh) and she points to how traditions for similar festivals not only differ on either side of the border, but also within the region. “In Purba Banga, if you go towards the northwestern regions like Rangpur, some homes have this tradition of not cooking with salt on Sankranti. In other homes, only pithe-puli is cooked.”

In West Bengal, there is the tradition of Auni biuni. “I heard about this recently. Auni biuni is a chhora (poem) that women sing during the puja. And there are families who only serve dishes cooked with rice on Poush Parbon.”

Through her work, Koyel has had the opportunity to interact with many people working with Bengal’s food history. She recalled a nugget of information from someone who studied rice varieties in Bengal. “This is much later history, of course. There are three seasons of rice growing in Bengal — winter, summer, and the time around October-November. The last one is the rice that is harvested now, during Poush Sankranti.”

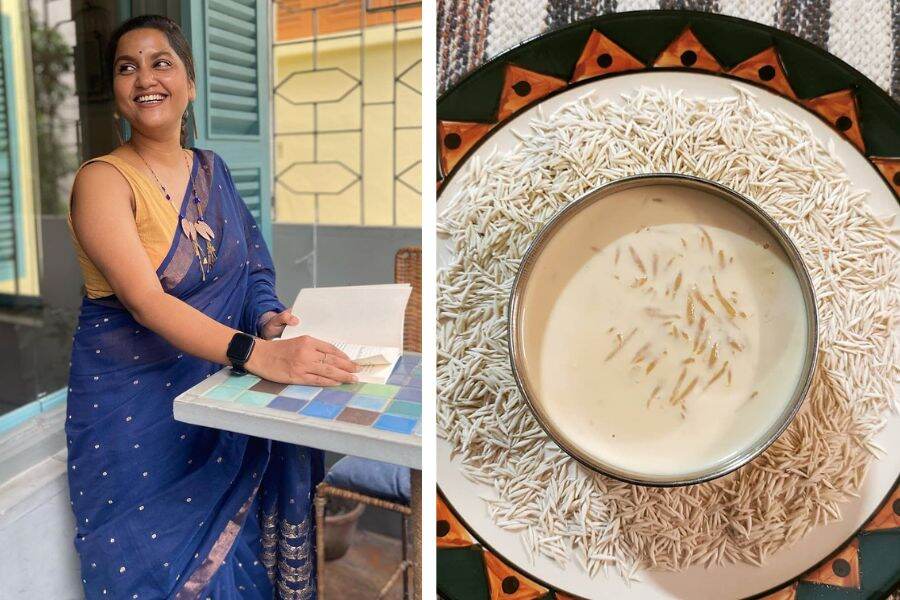

There were at least five varieties of ‘pithe’ made for Poush Sankranti celebrations at the chef’s ancestral home Shutterstock

Childhood memories

Her own family celebrated Chaitra Sankranti in a much bigger way than the Poush one, but she remembers a few rituals that were mainstay. Koyel heard stories from her parents about a Vastu Puja that would happen every year during this time in their ancestral home in Bangladesh. The mornings would see a dodhikorma (a mix of flattened rice, yoghurt, gur), but evenings would be for making pithe — “there were at least five varieties made, I’m told!”

What she always found interesting was the concept of niyom or traditions with regard to certain dishes being made in certain households. For example, many Bengali families don’t make certain pithe — “like bhapa pithe and shora pithe,” said the chef — because no one ever made it in the family, or the occurrence stopped with a certain generation. “I was often told that we didn’t have the niyom of making bhapa pithe at home because my thakuma never made it or mentioned it. I would tease my mother that they were just taking the easy way out in the guise of tradition.”

Another rather unique food tradition of Koyel’s family is the hathambol. “It’s a shinni-like concoction, like a thick drink, made with freshly ground rice flour, grated coconut, gur, and interestingly Gondhoraj lemon! ‘Ambol’ usually refers to the sour element in Bengali cuisine, so I guess with the use of the lemon, that’s where it gets its name from.” While Koyel does not remember the taste of this drink, her mother insists that she had it as a child.

The one thing that Koyel does distinctly remember, and is a must for every Sankranti even today is making choshi pithe. In her large joint family, there was always a “girl gang” at home who would sit together to make the choshi the night before.

“I also miss going to the mela and dashing straight for the pithe stalls!” said Sienna’s sous chef. Growing up outside the city (in Sodepur), meant that there were multiple winter fairs. “All of them had stalls where the rice would be ground fresh in a dheki and different kinds of pithe were made. That smell of freshly ground rice is a wonderful aroma you will only experience when rice is ground in a dheki!”

‘The aroma of rice being ground in a ‘dheki’ is one of a kind,’ says Koyel Shutterstock

Celebrating at Sienna

While Sienna does not have a Sankranti-special menu (though they are working on some new dishes we’re eagerly looking forward to), the team makes it a point to celebrate in their own way with the Sienna family. Of course, that includes making choshi pithe.

The unique pithe also features sometimes on their Bajar to Table tasting menu, something the chef is very proud to have pushed for. “Many of us, even in the kitchen, live away from our hometowns and families and we miss the traditions and festive food from home, so we get together to make some of these dishes.” It’s their little way of making sure everyone misses home just a little less on festive days.

A ‘choshi pithe’ recipe from Chef Koyel Roy Nandy

“My mother always said, domka jaal e chitoi pithe, nibhu jaale puli pithe.” (A high flame for steamed pithe and a gentle flame for the ones in a kheer.)

Ingredients

For the choshi:

- Fresh coconut paste 100gm

- Liquid nolen gur (jhola gur) 60ml

- Rice flour 160gm (could be adjust if more needed)

- A pinch of salt

- Water 80ml

For payesh:

- Milk 2 litre

- Prepared choshi 50-60gm

- Ghee 1tbsp

- Nolen gur (liquid or solid) 100gm, or more depending on taste

Method

For choshi:

- Make a fine paste of the coconut, without adding any water, by grinding freshly grated coconut using a mortar pestle or grinder.

- Set water, salt on the boil in a kadhai. Once the water starts boiling, add the coconut paste, jhola gur and cook for about 6-7 mins on a low to medium flame.

- Add rice flour into the mixture, little by little and make sure to stir continuously with a wooden spoon or spatula, cooking for another 8-10 mins on a low flame.

- Keep stirring the mixture so it does not stick to the wok, until it comes together in a dough and the coconut releases oil and aroma. Once the coconut releases oil, take it off the flame.

- Transfer to a clean working surface and knead it till it becomes a nice, smooth dough. Cover it with a clean, dry cloth and keep it in an air-tight box.

- The making of the choshis has to be done fast so the dough does not dry out.

- The little choshis look a lot like orzo pasta and take some practice to make. Take a very small portion of dough and roll it into a thin long string. Break off a small potion with your right hand and using your left palm, roll it and shape it into a little dumpling resembling a grain of rice in shape.

- Spread out the choshi on a newspaper and leave it to dry overnight.

For payesh:

- Place the milk on boil in a thick-bottomed vessel. Once the milk has boiled, lower the flame and stir occasionally.

- In a small frying pan, add some ghee and fry the choshi on a low flame until they are fragrant but not browned.

- Once the milk has thickened a little, add the roasted choshi and cook on a medium flame. Add the gur as well and keep cooking.

- Once the payesh has thickened, take it off the flame and let it cool before serving.