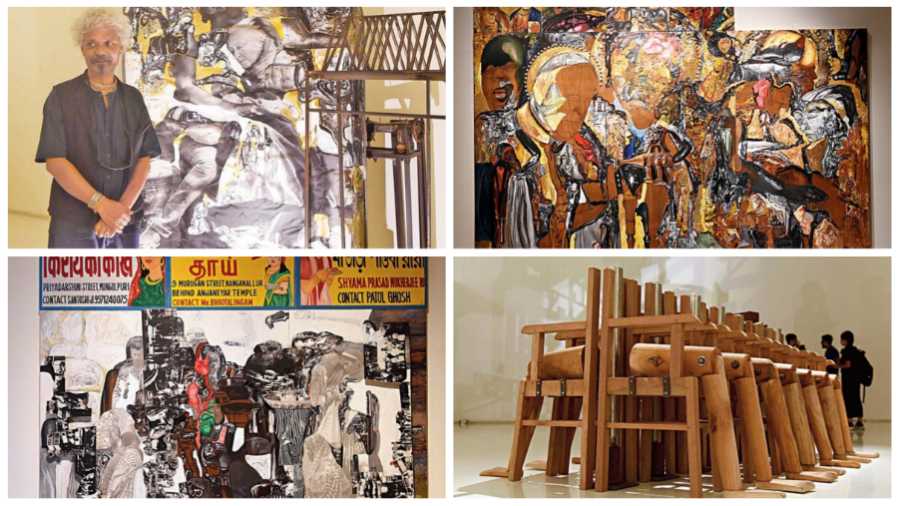

Probir Gupta is an activist first. The artist in him is overpowered by his activism. And driven by it, his artwork voices the pain, agony and struggle of those wronged in society — in India and other geographies, on large canvas and installations. The overtone of black and grey in his work reflects the trauma of the men, women and children from different castes and communities he has come in close contact with. “Being a cultural practitioner, things happening around me disturbs my consciousness. I cannot paint happy pictures because I am always political in mind,” concedes Gupta who was in the city for his solo exhibition — Room Full of Mirrors at Kolkata Centre for Creativity. Though the Delhi-based artist is a regular visitor to Kolkata, this was his solo exhibition after 14 years. The Telegraph caught up with the activist-artist at the preview. Excerpts:

You are showcasing your work in Kolkata as a solo artist after 14 long years. What kept you away from the city’s galleries?

Kolkata hasn’t left me and I cannot leave Kolkata. So, though I come here quite often, I am here with my solo exhibition after 14 years. My first solo here was in 2007. One was in the Academy of Fine Arts and the other one in another gallery on Park Street, which is now shut. Post that, I participated in a few curated shows here but it feels great to be back with a solo show. Also, this is my first time at Emami Art, and I am looking forward to more such shows.

Your artwork is always large and the 10 exhibits here follow the same dimension. Tell us more about it.

This is the scale I work in. My entire body has to be involved in the process and not just my wrist or my arms for that matter. It’s my entire body — physical and mental, which is invested in the artwork. That is why they become large, I cannot control it.

The overarching theme as we know and see is pain and suffering of the disadvantaged. Tell us how these themes manifest in your artwork.

Fifty per cent of my work happens in my studio and the other 50 per cent happens in my spending time with different communities. I meet people who are not in a stable situation and try to help them out; these are my resources. It’s my ideology, philosophy and activism forming 50 per cent of my work. And what I do in my studio is also a manifestation of my activism. So, I call myself an activist, completely. Since 1996, I have been working on such themes and I have direct social involvement.

These are works which are manifestations of different situations of people in the society. The country is getting unbelievably communal, which is very dangerous. For instance, The Archive centres around a wall from the Muzaffarnagar riot. That wall stood witness to the wail and cry of innocent people subjected to rape and murder. I have embedded the ECG diagrams of paranoid people from different places, on the wall’s body, to show how heartbeats look like when someone is under trauma or terror.

If we take the last 14 years, how has your art evolved?

I am living in my times. From 2014 things have changed like mad.

Does it scare you?

Of course, it scares me. However, the feeling is not there when I am here in Kolkata. It’s among the very few states in India where we can speak our minds. The attack is not physical but cultural as well. As a cultural practitioner it disturbs me. I am always political in my mind and hence painting happy pictures doesn’t come to me.

Which is your latest installation?

The Spine. It’s one of the sculptures I made in Kolkata involving local woodworkers and young artists. It’s a symbolic ode to the hands and legs buttressing the pillars of social order.

What are you working on next?

There are lots of things. My work is all about human condition and situation and it’s not restricted to local scenarios. It’s about the brutality and discrimination that people face across geographies. I am constantly keeping myself informed so it will certainly lead to a new piece of art that will again speak volumes of my art and activism.

Pictures: B. Halder