A writer, commentator, playwright, podcaster, and CEO of Almast Media - Giaea LLC, Sarbpreet Singh has lived a life looking for his roots, while also excelling in the corporate world. However, the journey in search of his origins was one that he started only after he had left India to pursue a career in the United States. Over three decades he has written and translated extensively and his works have been informed by the Sikh sacred tradition as well as the Sikh secular poetic tradition. The founder of The Gurmat Sangeet Project, a nonprofit dedicated to the preservation of sacred Sikh music – Singh is also a podcaster whose show, Story of the Sikhs, has listeners in 90 countries and is currently in its fourth season.

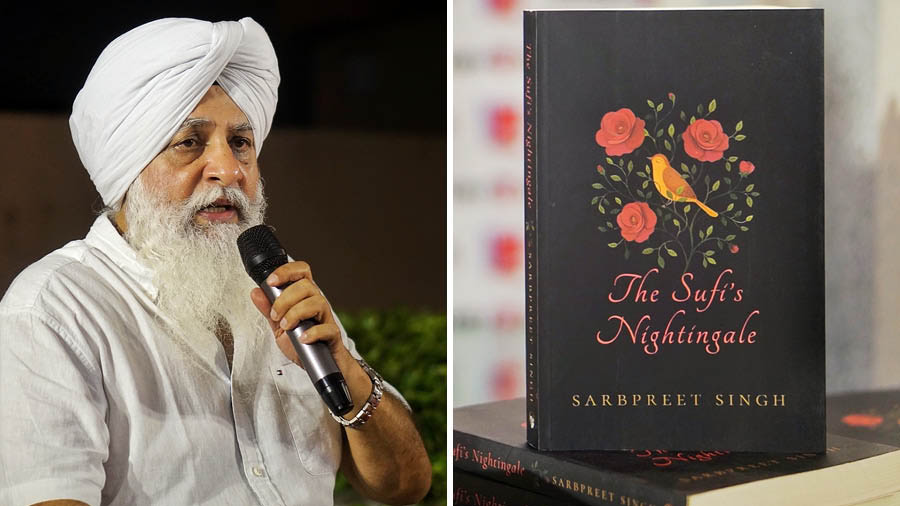

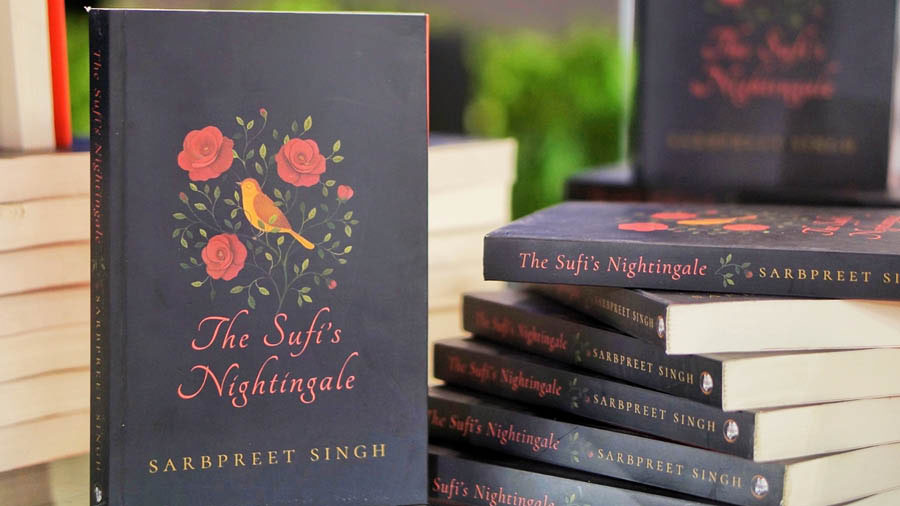

His works, such as Kultar’s Mime (2016), Night of the Restless Spirits, The Story of the Sikhs: 1469-1708, and The Camel Merchant of Philadelphia, among others, talk about the history and condition of Sikhs across various time periods. His latest book, The Sufi’s Nightingale, published by Speaking Tiger Books fictionalises the life of the 16th-century mystic and poet of Punjab, Shah Hussain (the master of the kafi form of poetry), and his love for a Hindu boy, Madho.

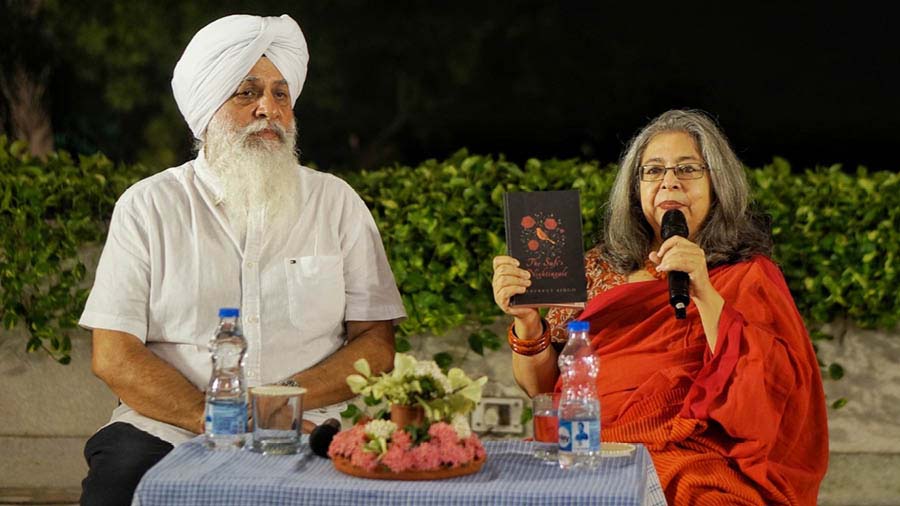

September 10 saw the launch of the book at Birla Academy of Art and Culture, organised by Speaking Tiger Books, where Singh was in conversation with editor, writer and translator Anjum Katyal.

Singh was in conversation with editor, writer and translator Anjum Katyal

An inseparable bond

Speaking of Shah Hussain, Singh remarked that Hussain was recognised as one the greatest poets in the Punjabi language, known for his kafis – a form of poetry that is meant to be sung.

“There are some Sufi poets who have gained a lot of prominence in modern times. Baba Bulleh Shah is probably the most well-known. Shah Hussain is somewhat lesser known, but for aficionados of Punjabi poetry, he ranks right up there in terms of the beauty of his poetry and emotions,” said Singh.

But how did he come across the story of Madho and Lal Hussain? Singh revealed that he read about them when he was researching for his book The Camel Merchant of Philadelphia, which revolves around the court and times of Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

Merging of names and identities

“I first encountered Madho Lal Hussain rather obliquely, when I was researching The Camel Merchant. I didn’t know at that time that I would get to know Madho Lal Hussain so well. But I read European accounts of a particular traveller who had visited Maharaja Ranjit Singh's court and said that every Basant Panchami, the first day of spring, the emperor would go to the tomb of one Madho Lal Hussain to pay his respects. I remember thinking at that time that the name Madho Lal Hussain made very little sense.

And quite to my surprise, I learned that Madho Lal Hussain referred to not one individual but two: Madho and Lal Hussain. So some historians called them Madho Lal and Hussain. That's incorrect. Lal Hussain was known before he became Shah Hussain, because he used to wear red robes. Madho was his dearest disciple and successor. Ultimately, they were so close that their very identities and names merged,” he said.

Copies of the book at the launch

Between fact and fiction

The book is an amalgamation of fictional and historical characters. Some historical characters that have made an appearance in the book are Mughal emperor Akbar, Shah Hussain himself, Guru Arjun, the fifth Guru of the Sikhs, and others; while fictional characters such as Maqbool, who later becomes Maqboola, help in taking the narrative forward.

The Camel Merchant of Philadelphia, which is a historical non-fiction, speaks about the true facets of Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s court. “The topic is historical, but the focus is very much on writing something that can engage the reader. So, from that perspective, these beautiful detailed descriptions of battles and places and people that you find in epic poetry, and you don’t find in history books, is what inspires my creativity,” elaborated the author.

However, Singh hopes that people repeat the positive aspects of history rather than committing the same mistakes.

Capability over religion

“There were many things in Ranjit Singh’s court that were far ahead of their time. One of them was the fact that even though Ranjit Singh was a Sikh monarch, when it came to building his court, he didn’t favour Sikhs over non-Sikhs. There were Sikhs, but there were also many able Hindu generals. His chief diplomat was a Muslim. Hindus and Muslims enjoyed tremendous positions of power. His court included many Europeans as well. So the one big lesson we learn from that is, your background, who you are, which faith you practice, whether you are highborn or lowborn, whether you came from a rich family or a poor family – none of that matters when it’s weighed against your capability. Now this should be a fairly obvious thing to understand, right? But sadly it's not. To this day we see so much tribalism everywhere. Rather than bemoaning the fact that we keep making the same mistakes, I would much rather focus on some of the wonderful things that we saw happening in history that the world probably needs to bring back,” he explained.

The author enthralled the audience by rendering ‘kafis’ that he had composed

Translating to the spirit

Most of Singh’s works are inspired by and drawn from Punjabi secular and sacred literature. The Sufi’s Nightingale is no different, as the translated versions of the poetry of Shah Hussain feature in the book. “My books on Sikh history read more like works of literature than works of history, and they are heavily informed by our sources. So, there are lots of translations of poetry from the Sikh sacred tradition and also the secular poetic tradition,” said the author.

But the author who taught himself Gurmukhi and Braj Bhasha says that translating is always a “rewarding” experience despite it being difficult.

"So, you know, the problem is this: when you translate anything, you must want to be faithful to the original. But in the case of translating spiritual poetry, often, if you try to translate it faithfully and try to translate every word, what you end up with is prosaic poetry. The beauty of the original, or what Indian aesthetics would call the bhaav, or the essence of the original, is lost. This is constantly a challenge. This was important to my newest book as well, because this book is completely inspired by the poetry of Shah Hussain. I constantly make an effort to translate the spirit, which means that I am just trying to convey at least a modicum of the original sentiment of the original poetry to the reader. I can try translating for 100 years, but I will never be able to convey the full force of the original writer's intent,” noted Singh.

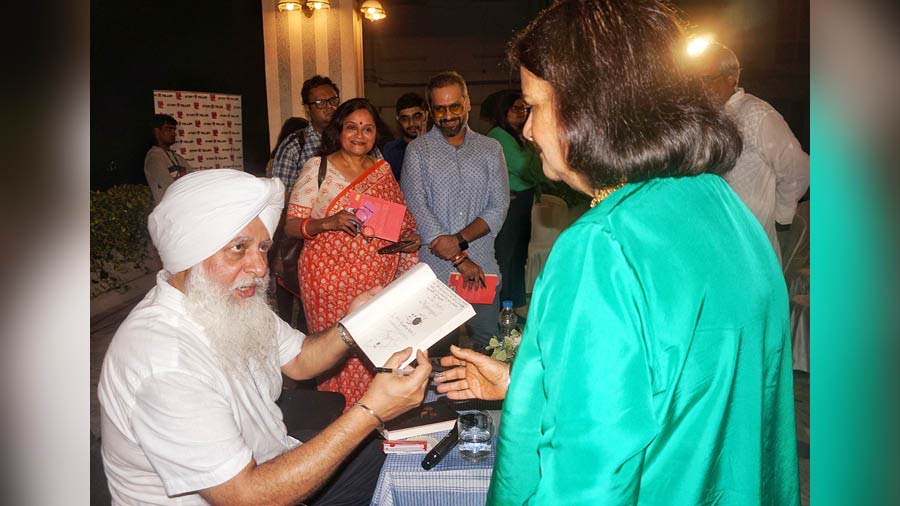

Singh signs copies of his book

‘Love and tolerance is the central message of the book’

The Sufi’s Nightingale revolves around the relationship between Madho, a Hindu boy, and Lal Hussain, a Muslim murshid, thereby underlining the theme of harmonious coexistence.

“The book's central message is love and tolerance, encompassing a wide canvas that addresses events in Punjab at the time. It fundamentally conveys our culture’s ability to bridge religious and societal divides. In the story, Hindu characters interact with Muslim mystics, Murshid, and Mureed from one faith, and Sikh characters engage with them. This isn't fantasy; we inhabit a land where pluralism has thrived for many years.

So, is there a philosophy that guides him? “Guru Nanak’s ideals, including equality, social justice, and opposition to tyranny and exploitation resonate with me. Despite my imperfections, I aspire to live by these values. Guru Nanak’s strong stance against Babar’s tyranny, documented in Babar Bani, influenced Guru Gobind Singh’s later actions. Sikhism promotes active engagement with the world, exemplified by Guru Nanak’s engagement with his community while being a spiritual leader,” concluded Singh.