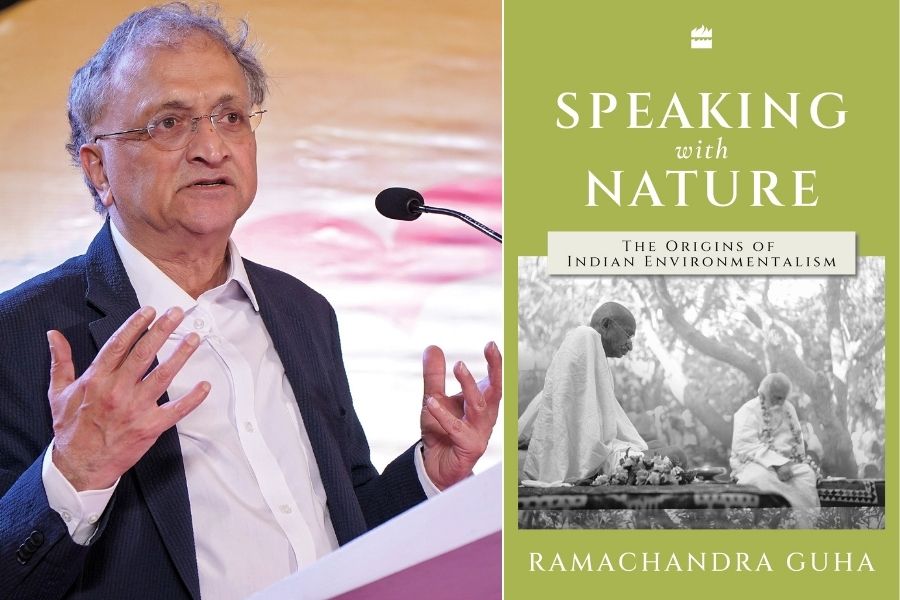

Speaking with Nature: The Origins of Indian Environmentalism (HarperCollins), Ramachandra Guha’s latest book, seeks to trace a ‘prehistory’ of environmentalist thought in India, in an effort to debunk the familiar Western perception that countries in the global south are “too poor to be green”. As in the case of our key democratic principles, numerous progressive movements and a range of modern institutions along with traditional scholarship attribute the origin of environmentalism to Europe and North America. In literature and culture, one thinks of the Romantics and their resistance to the industrial machine, one also thinks of RW Emerson and HD Thoreau.

Guha’s book effects a rupture in that narrative, drawing upon the work of 10 key thinkers — Rabindranath Tagore, Radhakamal Mukerjee, JC Kumarappa, Patrick Geddes, Albert and Gabrielle Howard, Mirabehn (or Madeleine Slade), Verrier Elwin, KM Munshi and M Krishnan — whose contributions reflect the existence of precocious and pioneering ecosophies of various stripes in the subcontinent much before the kind of focussed scholarship that the urgencies of climate change have necessitated today.

‘Kolkata gave me a second chance at life’

Guha’s academic connection to Kolkata started with his doctoral dissertation on the Chipko Movement at IIM Calcutta Soumyajit Dey

On the final day of this year’s Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival (AKLF) held at Allen Park, Guha spoke about the book, giving the audience an overview and focussing on four thinkers from the 10 featured in the complete text: Tagore the poet, Mirabehn the social activist, Patrick Geddes the scientist, and M Krishnan the naturalist. Speaking with Nature is, of course, not Guha’s first foray into researching the ecological history of India, and he said that the book was “the culmination of a journey that began in this city over four decades ago … this city gave me a second chance at life”.

After studying economics in Delhi for five years, Guha enrolled in the sociology department at IIM Calcutta, where he would go on to develop his doctoral dissertation on the Chipko Movement, “a landmark in global environmentalism that would show the world that poor people could be concerned with environmental sustainability too”, which was published as The Unquiet Woods: Ecological Change and Peasant Resistance in the Himalaya in 1989. Since then, his work with Madhav Gadgil on Ecological Equity: The Uses and Abuses of Nature and This Fissured Land: An Ecological History of India as also his Environmentalism: A Global History are some prominent examples of his continued engagement with questions of ecological extraction and disenfranchisement that have plagued India.

The four dimensions of Tagore’s ecological thinking

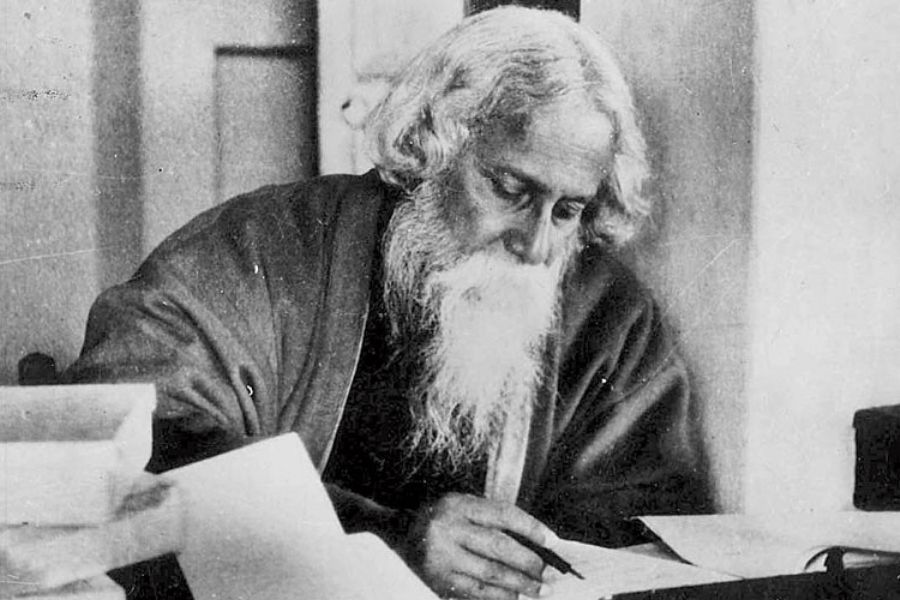

Guha referred to Tagore as the “myriad-minded environmentalist” TT archives

In Speaking with Nature, Guha chooses to present a “history of ideas” otherwise neglected, in the hope that these thinkers might influence the decisions of policy-makers today. Aware of his audience, Guha began his talk with Tagore, the “myriad-minded environmentalist” (an allusion to Rabindranath Tagore: The Myriad-Minded Man, a magisterial study by Krishna Dutta and W Andrew Robinson) whose ecological thinking Guha categories into four dimensions: the aesthetic dimension, captured in much of his poetry as also in letters written to his nieces from the estates in the countryside; the educational dimension, exemplified in the pioneering environmentalist pedagogy of Patha Bhavan and Visva Bharati; the political dimension, which saw Tagore indicting the Western colonialist machine as one predicated upon ecological exploitation over and above political and economic disenfranchisement; and the prophetic, with Tagore imagining a new race of man that would colonise the moon, having plundered our planet to exhaustion.

“Through machinery of tremendous power, this new race made such an addition to their natural capacity that their career of plunder entirely outstripped nature’s powers of recuperation,” read Guha, quoting a 1922 address of Tagore’s in Sriniketan. Indeed, as Guha pointed out, “in 2025, there is a great deal of talk about environmental education… but when I was a school student in the 1970s, all our education was inside classrooms and laboratories”.

‘There are still parts of Kolkata that are relatively well-preserved… In Bengaluru, we’ve lost everything’

Guha spoke at length about the contributions of two foreigners, Mirabehn and Patrick Geddes Soumyajit Dey

Guha then discussed the contributions of Mirabehn, the Englishwoman Madeleine Slade who became MK Gandhi’s disciple and was jailed numerous times for her participation in the Freedom struggle. Following Gandhi’s death, she left his ashram in the late 1940s to move to the Himalayas, where she worked on water conservation, forest management, the promotion of species like oak, which were much more valuable to the local economy and ecology than the ones being planted by the Forest Department and its paper mills for commercial purposes.

Another foreigner whose work Guha drew attention to was the Scotsman Patrick Geddes, a town-planner among other things, whose passionate interest in understanding how cities grow drove him to conceptualise ways of making, Guha explained, “cities less dependent on the resources of the environment and more self-contained are more ecologically harmonious.” Between 1914 and 1924, Geddes spent long years studying small, medium and large cities and towns in India, from Thane to Lahore to Mumbai, upholding what Guha called a “respect for nature”, insofar as the city would cease to pillage the resources of the countryside and focus on reviving its own water bodies instead, alongside respect for democracy and tradition. Guha remarked, “There are still parts of Kolkata that are relatively well-preserved, around BBD Bagh, the old historic Kolkata. In Bengaluru, we’ve lost everything — all our old buildings, all our parks have gone.”

‘Even if climate change did not exist, India would be an environmental disaster zone’

According to Guha, “No Indian government has paid adequate attention to ecology.” TT archives

Finally, Guha spoke about M Krishnan, a naturalist, photographer and “ecological patriot” fighting against foreign invasive species, who got his “rozi roti” from this city, writing a fortnightly column for The Statesman called ‘Country Notebook’. “He was a marvellous prose stylist, the best India has ever seen in the English language, second only perhaps to Vikram Seth,” Guha claimed. Having curated an anthology of Krishnan’s writing called Nature’s Spokesman: M. Krishnan and Indian Wildlife, Guha said, “It gave me more pleasure, joy and a greater sense of achievement than any book I’ve published of my own.” Krishnan’s deep and abiding love for our indigenous flora and fauna, our ocean and terrestrial landscapes, reflected, for Guha, a heartening and heartfelt environmentalism that encouraged people to discover, understand and love this heritage “as one of the most deeply satisfying things that India has to offer its people”.

Before concluding the talk with Tagore and his vision of the moon-colonising race, not so distant after all from the Elon Musks of our age, Guha pointed to the deeply vulnerable state of India’s ecology today: “Even if climate change did not exist, India would be an environmental disaster zone. No Indian government has paid adequate attention to this. The greatest threat to India today is the devastation of the natural environment. It is as great a threat as the persecution of minorities, the destruction of institutions, and the building of personality cults.”