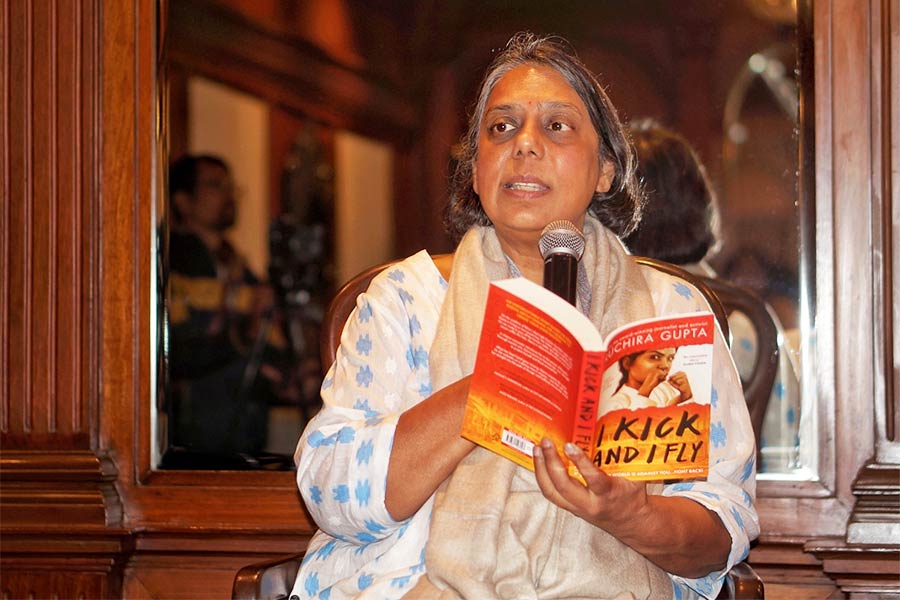

Born into the Nat tribal community that had been criminalised under the colonial Criminal Tribes Act of 1871, Heera, a 14-year-old girl, knows that her destiny is to be sold into sex work. That had been the destiny of the women in her community for decades. For the longest time, she expected nothing different from her life until she took up kung fu at school. Being good at kung fu opened up avenues that she did not know could be available to anyone who belonged to an impoverished and marginalised community. Kung fu gave her wings and she let her ambitions soar. This is the crux of journalist and activist Ruchira Gupta’s moving debut novel, I Kick and I Fly.

At the latest session of An Author’s Afternoon, organised by Prabha Khaitan Foundation in association with Shree Cement Limited, with My Kolkata as digital partner, Gupta was in conversation with writer, editor, and translator Anjum Katyal. The event saw her discussing the predicament of the Nat community, her initiation into activism, and more, much to the delight of a rapt audience at Taj Bengal.

Mallika Verma, Ehsaas Woman of Kolkata, delivered the welcome note on behalf of the Foundation while Harshavardhan Neotia, chairperson of the Ambuja Neotia Group, introduced Gupta before the programme got underway.

The tale of the Nats and a cycle of oppression

Gupta (left) in conversation with Anjum Katyal Soumyajit Dey

Speaking of the Nats, Gupta noted that they were a nomadic community who migrated from the forests to the plains with their goats and sheep. Apart from selling their dairy products and medicines, they also eked out a living by performing wrestling acts and acrobatics. The enactment of the Criminal Tribes Act had profound consequences on the Nats. They were one of the 16 tribes who were not only labelled as criminals but were subjected to a catalogue of restrictions, such as being prohibited from wearing shoes, hats, riding horses, and living in roofed houses.

Forced to seek precarious land for survival, they ended up squatting on government or zamindari land, engaging in menial tasks for the landowners while also pushing their women into sex work. This led to a cycle of oppression, termed intergenerational prostitution, where prostitution was passed from mother to daughter and pimping from father to son.

After Independence, Jawaharlal Nehru took steps to repeal the law, known as the Denotified Criminal Tribe Act. However, the stigma persisted, with the police continuing to target and discriminate against the Nats.

When Gupta immersed herself in the fight against sex trafficking, her initial focus was on Mumbai. Gradually, she discovered that numerous women in the beer bars and brothels of Mumbai hailed from the Nat tribe. As she delved deeper, she found the Nats in the same village where she grew up, in a small town on the Nepal-Bihar border called Forbesganj.

“In this village, a marginalised community lived along railway tracks, oppressed by zamindars, and their land was ironically named Khawaspur, where one could eat and live in exchange for performing various chores. The reality was grim, with 72 shacks made of plastic sheets and bamboo serving as makeshift brothels. This strip, known as Laltain Bazaar in Bihar, had its own dynamics. A yearly fair in Forbesganj, the place where I later set my novel, revealed the true nature of things. Alongside agricultural transactions, girls were being auctioned at orchestra parties, leading to them being trafficked to destinations like Mumbai, Delhi, and even Europe,” explained Gupta.

‘Their story, though rooted in harsh realities, needed to be shared as a tale of hope’

Gupta’s focus was on educating the children of prostituted women to break the cycle of intergenerational prostitution Soumyajit Dey

Realising that a red light district existed in her own village, Gupta felt compelled to take action beyond the confines of Mumbai, since Mumbai had its own NGOs. Establishing a community centre in the heart of the red light area, her focus was on educating the children of prostituted women to break the cycle of intergenerational prostitution.

“To address immediate concerns, we initiated a mid-day meal programme, realising that hunger was a barrier to learning. Despite their progress, first-generation learners were discriminated against in schools due to their origin in the red light area. The children themselves would heckle the teachers as they were dependent on drugs and alcohol. The girls also hated their bodies as they knew that their bodies were the reason why they were trapped.

“In response, we took proactive measures, including introducing kung fu training to instil confidence and resilience among the children. Within months, the kids began to break burning tiles and win medals. These victories not only transformed the children’s perception about their bodies, but also changed their community’s perceptions about them. This made me believe that their story, though rooted in harsh realities, needed to be shared as a tale of hope,” said Gupta.

A career dedicated to activism

While working as a journalist and travelling through the hills of Nepal, Gupta came across villages that had no girls. She followed the trail and reached Mumbai, where the missing girls were locked up in tiny rooms and sometimes even inside cages in brothels. That is when she decided to make the documentary, The Selling of Innocents, which won an Emmy Award in News and Journalism in 1997.

“[After winning the Emmy] I went back to the brothels and showed them the award, feeling good about myself. But the women said I needed to do more, since I had access to English and money. So I agreed to help them while making the mothers promise that they would stand by their daughters. That’s how we started Apne Aap (an NGO). We hired teachers and started a school. The mothers had simple dreams: a school for their children, a room of their own where they could sleep safely with their daughters, a job at an office that provided pensions, fixed monthly income, no violence, and punishment for perpetrators. All of that became Apne Aap’s business plan… As an activist, I have learnt that solutions come from people affected by problems and not from the top. If you want people to listen to you, you have to listen to people,’’ noted Gupta.

‘I wanted readers to delve into the hearts and minds of my characters’

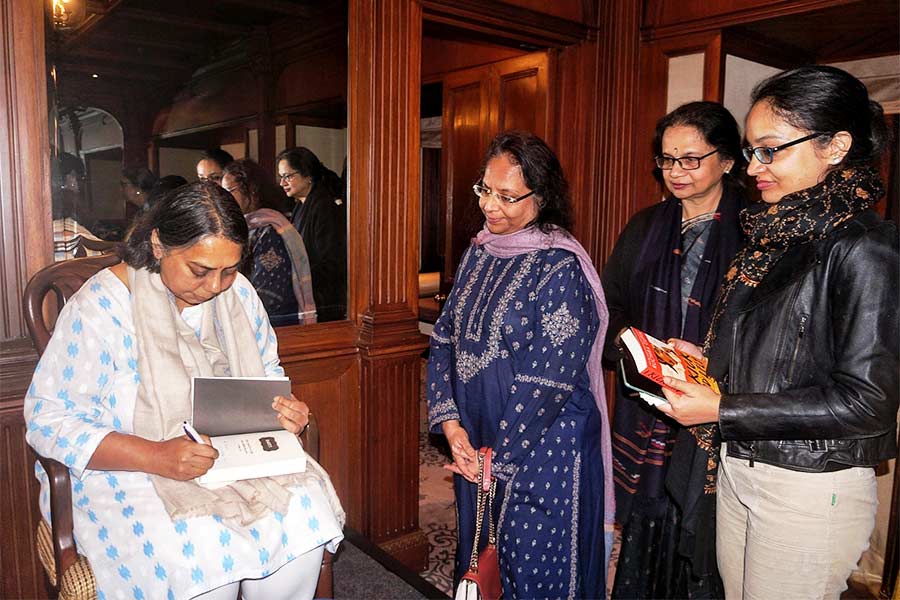

Gupta signing copies of her book, ‘I Kick and I Fly’ Soumyajit Dey

When asked why she decided to write fiction even though she had the material that would make for a compelling non-fiction book, Gupta emphasised on how she wanted her readers to consider the characters of her book as real individuals.

“I wanted readers to delve into the hearts and minds of my characters. Drawing from three decades of first-hand experience in these communities, I’ve encountered laughter, hope, sorrow, complicated family dynamics, friendships, courage and resilience. I believed that presenting it as fiction would allow me to explore the emotions of the characters better. That’s why I wrote this book as a crossover, which can be read by both children and adults. It’s fast-paced, and I call this genre the social justice genre. I want people to read and enjoy it and learn lessons without it being preachy. Each incident is drawn from real life, which means that readers will find authenticity while also finding adventure,” concluded Gupta.

Guestspeak

Soumyajit Dey

If we can have more discussions like this with younger girls, we can inspire them to action while also making them aware of the problems plaguing our society

Shamlu Dudeja, chairperson of Calcutta Foundation and SHE Foundation

Soumyajit Dey

Ruchira has always been an inspiration, but today I saw her in a new light. I didn’t know that this was a story that she had written and her message came across so well. Even though she is an Emmy-winning journalist, given her preoccupations with activism, it’s wonderful that she found the time to write a book. I’m really looking forward to reading the book.

Oindrilla Dutt, columnist and broadcaster

Soumyajit Dey

The conversation was lovely and enriching, and I learnt a lot from it.

Sambhavi Ghoshal, student of Loreto College

TT archives