The game of pasha played an important role in the epic Mahabharat. The 1970s and ’80s kids would remember Sunday mornings when BR Chopra’s serialised version of the epic on Doordarshan would show Shakuni (representing Duryodhan) winning Draupadi by casting a pair of stick dice. But the Sanskrit word pasha literally refers to the dice and not the game. The game is known as chaupar (also chopad or chaupad) and is considered as the origin of the popular board game (now also mobile game) of ludo.

Sujaan Mukherjee introduces Souvik Mukherjee to the audience

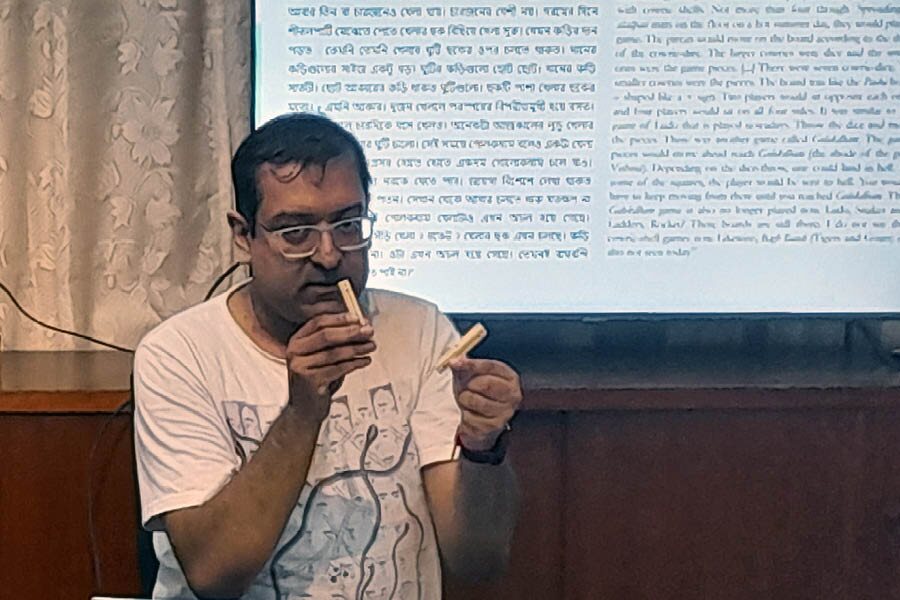

At 6pm on September 7, the Birla Academy of Art & Culture (BAAC) presented a talk on the game of chaupar, titled ‘Chaupar from Puranas to Paras’. Souvik Mukherjee, a faculty member at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata, presented the talk. Mukherjee, whose MPhil and PhD were both centered around video games, runs a board game museum named after his late father-in-law Goutam Sen, an avid chess enthusiast, at his Ballygunge Circular Road residence in south Kolkata.

A ‘chaupar’ board with pieces, two sets of stick dice and seven cowrie shells

The talk began with an introduction from Sujaan Mukherjee, senior curator of BAAC. He said: “BAAC presently has two permanent galleries dedicated to traditional sculpture and miniature art. The third gallery is on modern and contemporary art, which is presently under renovation and likely to reopen early next year. But apart from that, BAAC has thousands of undisplayed artwork.” He further added: “We are planning a series of lectures, which will allow us to display our undisplayed artwork. The talk on chaupar will display two contemporary artworks on the game by two contemporary artists Sanjay Ashtaputre and Maniklal Banerjee.”

Souvik Mukherjee presents the topic ‘Chaupar from Puranas to Paras’ with the artwork of Maniklal Banerjee (left) and Sanjay Ashtaputre (right)

Souvik Mukherjee’s presentation started with the history of chaupar and its connection with the very popular board game of ludo. He said: “The word ‘ludo’ has a Latin origin and means ‘I play.’ The game traces its origin to the chaupar from India. It was introduced into England and Alfred Collier patented the game in 1891.”

He added: “In ludo, the board changed from crucifix to square and the cowrie shells or stick dice were replaced with cubical die. Also, the traditional cloth crucifix was replaced with a square cardboard. Although usually played on cloth boards the game is also played on boards permanently etched on public places like temples and courtyards. The courtyard in Fatehpur Sikri near Agra has a giant chaupar board. Akbar used to play the game with pieces replaced by dancing girls.”

The second ‘chaupar’ board on display

The lecture moved to different versions of the game played across the country. Mukherjee narrated: “Not only do the rules differ, it is also known by different names in different parts of the country. In Sylhet (Bangladesh), it is called das – panchis, meaning ten – twenty-five, representing the minimum and maximum number obtained by casting seven cowrie shells.”

The lecture moved on to the two paintings displayed at two corners of the hall. The first by Maniklal Banerjee was drawn in 1990 and shows two tribal women playing the game — no wonder the game has spread across all demographies. The other one, by Sanjay Ashtaputre, was drawn in 2002. It shows the game through a puppet show. The player as well as his stick die is controlled by a set of strings.

(Left) Two sets of stick dice and (right) Seven cowrie shells, showing a combination of up and down positions

The session ended with a display of chaupar boards complete with pieces and stick dice and cowrie shells. Two cloth boards were displayed. Also on display were two pairs of stick dice. The first stick die had numbers from 1 – 4, while the other had numbers 1, 3, 4 and 6. Also on display were a set of seven cowrie shells. These were thrown together and a combination of up and down determined the points. The demonstration was accompanied by a question-and-answer session.

Sujaan Mukherjee completed that session with promises of more such interactive sessions. He said: “A museum or gallery needs to be more interactive and such a session not only creates awareness but allows us to display unseen artwork. Moreover, it makes the gallery popular and attracts repeat visitors.”