A black backdrop, devoid of any stage set up. A music sheet stand. A peg table with a tumbler and bottles of water. And a spilling-at-the-edges amphitheatre at the Kolkata Centre for Creativity (KCC) packed with expectant faces on the evening of August 31.

The setting had more than a smattering of A-listers along with familiar faces from the city’s culture circuit. But, for once, there were no second glances to spare. Not even for Naseeruddin Shah, who waited patiently, in the second row, like the rest of the audience for the performance to begin.

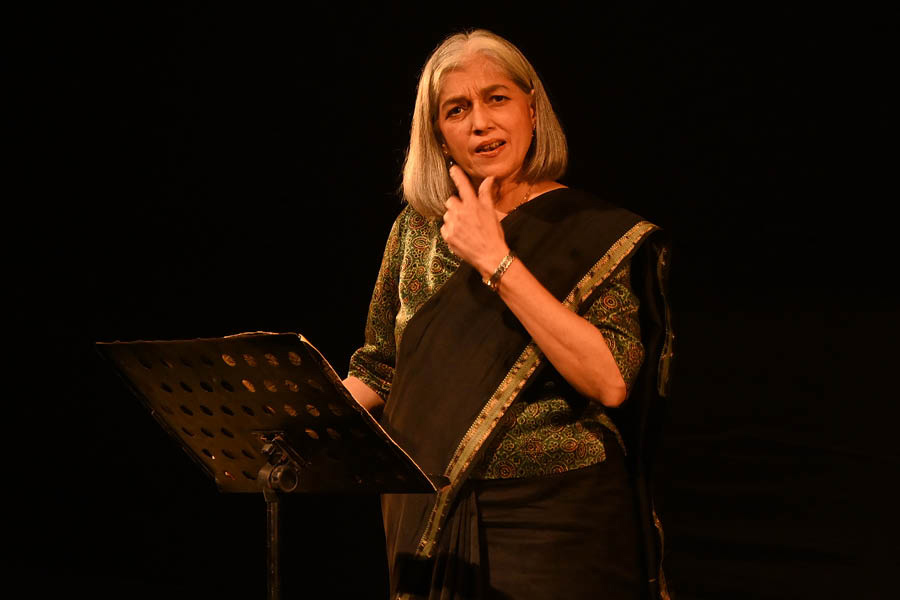

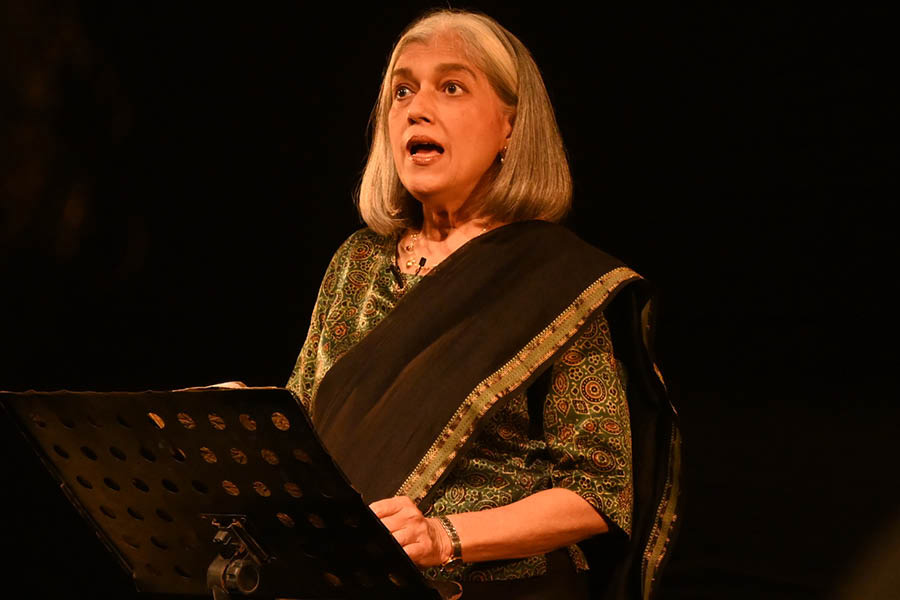

In walked Ratna Pathak Shah in a black sari that, instead of merging with the black backdrop, seemed to throw her famously expressive face and hands into stark relief, helped by the gleaming silver of her hair. Pathak Shah was about to perform dastaangoi, an ancient form of Urdu theatrical storytelling in which the face, the hands and the body, apart from the voice, are the only tools deployed. In the past, dastaangos, as dastaangoi practitioners are called, performed traditional tales. Today, the form is used to tell contemporary stories.

Over the next hour, Pathak Shah rendered the first-ever performance of Dastaan-e-Ashok-o-Akbar in Kolkata, penned by Ashok Lal as part of ‘Dekh Rahe Hain Nayan’ — a three-day festival presented by KCC and supported by Antiquity Natural Mineral Water — celebrating playwright Habib Tanvir’s life and contributions to Indian theatre, literature and art on the occasion of his birth centenary. The festival was curated by M.K. Raina and Tausif Rahman, with research and consultation by Anjum Katyal.

The story of Ashok and Akbar and a series of compelling coincidences

Pathak Shah’s performance was laced with several jibes and jokes that got the audience going

As a performing art form, dastaangoi “extends the boundaries of poetic recitation and takes it to the level of performance, as a form of narration it extends to dramatised rendition”, writes Mahmood Farooqui, one of the artistes credited with popularising the form in recent times.

On a humid Saturday evening, Pathak Shah started off in her inimitable style, with a disclaimer — the performance was to be in a foreign language, “yaani ki Urdu” — a not-so-oblique reference that drew gales of laughter and set the tone for the evening.

What followed was a dastaan of two young men, Ashok and Akbar, born and raised in different parts of undivided India, both enjoying a childhood rich in the cultural practices of their regions, not their religions. These two young men go on to become professors, each of the languages not thought to be ‘originally’ theirs. They teach at the same institute, not just as colleagues but as dear friends.

The story of compelling coincidences continues through Ashok and Akbar’s respective marriages to Sushma and Shama, and the subsequent appearance in the quartet’s lives of Azaad, a son shared and raised by both couples. The growing discomfort of those in their immediate environs stays constant as the tale progresses to 1992, a crisis encountered by Azaad and its denouement.

‘The challenge is to see that one doesn’t use dastaangoi as a way of showing off one’s skills’

‘Dastaangoi is accessible to actors at all levels of expertise,’ believes Pathak Shah

The telling was peppered liberally with quotes from poets ranging from Kabir to Nida Fazli to Kaifi Azmi. There were liberal lashings of socio-political commentary as well, especially when the story progressed to 1992. Delivered with Pathak Shah’s trademark lightness of touch, the performance’s humour complemented its intensity, as the audience enjoyed the jibes and the jokes.

As a storytelling form, dastaangoi allows raconteurs to morph into actors with a subtle tilt of the head and a slight gesture of the hand. Using her words and her body with all her mastery of her craft, Pathak Shah kept the audience in thrall, as the narrative arc of this fantastical modern fable unfolded. No mere feat, considering there were no other aids, props or tools to ease the dastaango’s task.

Addressing the challenges of dastaangoi, Pathak Shah observed, “Dastaangoi’s focus is on communicating — on transporting the audience through language and poetry. It offers actors and directors a chance to engage with text meaningfully, experiment with presentation and focus on getting their ideas across to the audience. It’s simple, direct and, most importantly, accessible to actors at all levels of expertise. The challenge is to see that one doesn’t use it as a way of showing off one’s skills. That one focuses on the essence of communicating ideas.”

As Pathak Shah wrapped up the tale, the hush that descended over the audience spoke more eloquently than the standing ovation she received a minute later.

But a question still lingered. Why this particular piece to celebrate Tanvir’s centenary year? Pathak Shah answered: “Habib saab’s work gave confidence to many of us when we were starting out in theatre. He showed us that there was much more to modern Indian theatre than box sets, fake realism and copies of Western productions. What better way to celebrate his legacy than with a modern dastaan? Through his plays, Habib saab reflected on the India of his times. Dastaan-e-Ashok-o-Akbar is Ashok Lal’s way of doing the same. I was delighted when Naseer suggested we do it. I feel what the story is saying is important to say in our society today.”

Reflecting on the special evening, Richa Agarwal, chairperson of KCC, said: “It was an honour to witness such a brilliant artiste like Ratna Pathak Shah bring to life the magic and mystery of Ashok Lal’s timeless tale. It was an unforgettable evening where tradition met contemporary narrative in the most enchanting way.”