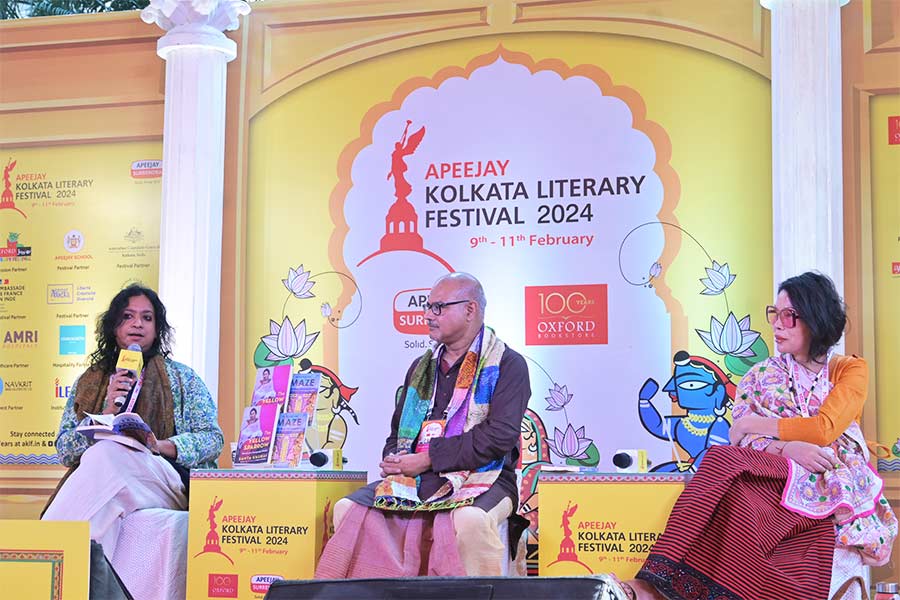

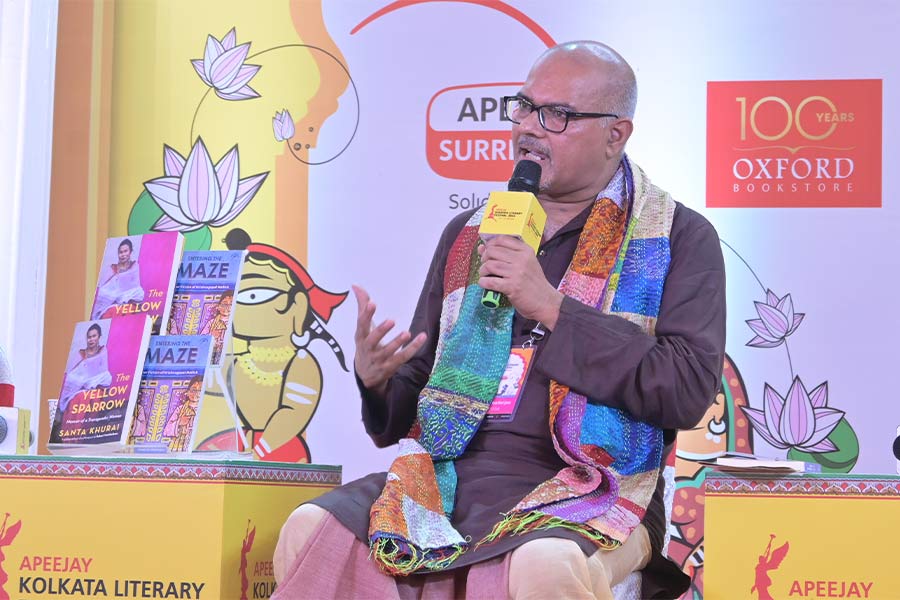

The 2024 edition of the Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival had a plethora of enduring conversations. Over the course of three days — February 9 - 11 — authors and experts took readers beyond their literature, to the ideas that inspire them. On February 9, in one such session titled Daring to be Different, human rights and gender activist Anindya Hajra spoke to Manipuri author Santa Khurai (The Yellow Sparrow: Memoir of a Transgender), and Kolkata-based professor and translator Niladri Chatterjee (Entering the Maze: Queer Fiction of Krishnagopal Mallick) about how their work raises questions around identity and alternate sexualities. My Kolkata brings you the excerpts:

Fiction v ‘faction’

Anindya: Niladri, what did you gather about Krishnagopal the writer, when you began translating this text?

Niladri: Honestly, Krishnagopal Mallick is very annoying (chuckles). He is an infuriating writer, because he refuses to be classed or categorised. He will constantly say that he’s writing fiction, but every novel has a character named Krishnagopal Mallick! You think that this is surely an autobiography, but he calls it fiction. At the same time, he repeatedly says that every single detail comes from real life. He is constantly playing with the audience’s expectations. But then, why bother to call it fiction? I think this is partly because some of the dialogue is made up. Moreover, autobiographies expect a certain rigorous adherence to truth, which he may not have been interested in. The text looks and feels like an autobiography, but he refuses to call it that.

Anindya: Talking about a rigorous adherence to truth, this is your autobiography Santa, but I have also known you as a poet and activist. How non-fictional is this non fiction?

Santa: Writing poetry allows me to express my deepest emotions through high literary values, while writing memoirs is all about facts. They sometimes have a limitation, as you cannot put anything that isn’t happening. Poetry allows me to express a lot of the feelings within me, but memories are about memories. With poetry, you can map a moment the way you want to.

Queer narratives

Anindya: So it is fiction, and yet non fiction. I’m quite interested in how these categories are constantly getting blurred in Krishnagopal’s case. The porousness between these categories really mimics the porousness that queer individuals have forever been talking about.

Niladri: I think about this very often while teaching literature. I sometimes ask my students, “What about fiction makes it fiction, and what about poetry makes it poetry?” They try to define it in a certain way, but I give the example of things going in a different direction. Every time you try to define a piece of writing under a certain form, be it a poem or novel, there will be another piece of writing that has gone against it. These categories are there for a purpose, but I believe it is the writer’s objective to push back.

Krishnagopal wasn’t an academic, but a journalist. He unconsciously asked very vital questions on what it means to speak the truth, and how it gets twisted. He wants to ask us whether truth exists, and how we can find it. While thinking about him, I also think about another queer writer, Truman Capote. His In Cold Blood is about a murder in the US, but the style of writing is fictional. Some people even describe it as ‘factional’. Is that a new thing? Subverting expectations is something Krishnagopal excels in. One of his stories is titled, Amar Premikara (My Girlfriends), and its first line says, ‘I am 112.5% homosexual.’

Niladri shared how Krishnagopal’s writings expressed an unabashed celebration of pleasure, moving away from queer narratives of suffering

Anindya: I also noticed that you chose to call Entering the Maze a ‘queer’ Fiction of Krishnagopal Mallick, instead of using the word ‘homosexual’, as he originally intended. Why is that?

Niladri: I’m glad you asked this. Firstly, because the term ‘homosexual’ belongs in the 19th century, and has a certain kind of pathologisation of sexuality buried in it, that I don’t agree with. The classic definition of homosexual is ‘someone who is not interested in women at all’, but Krishnagopal got married and had a child. While he claims the word homosexual, his lived life is not of a conventional homosexual. He is at liberty to call himself homosexual, but I’d use the word queer. In his life, he could be homosexual, but his fiction is queer because he is challenging a lot of normativity.

One of the fundamental norms he challenges is chrononormativity, which emphasises that you are supposed to behave in a certain way at a certain age. This particularly applies to sexuality, where society believes that you will start being sexual at 19, and stop at 39. If you are sexual before, your parents will take you to the psychiatrist. If you are sexual after, you’re a dirty old man, ek buddha jo sathiya gaya hai (an old man who has lost his mind). That is what Krishnagopal is pushing back against.

Anindya: That’s particularly interesting because Krishnagopal describes his 59th year to be the golden age of homosexuality. Poet Akhil Katyal also nods to the inherent ageism in queer spaces, and asks where transpeople disappear after their 40s. I also asked myself this when we walked down Park Street a couple of months ago for the Pride March.

Realities that inspire

Anindya: Santa, can you talk a bit about what led you to writing?

Santa: Writing allows me to bring out all the positive vibes within me. While growing up, I had no one to listen to my stories. In order to release the pent-up energy, I began writing about my challenges, relationships and feelings. I was heavily inspired by Hollywood movies and photo romances, which had a great presence in Manipur at the time. I also consider them to be the driving force behind the queer movement. They inspired me to love. When I went through those magazines, I saw myself in them. When I watched Pretty Woman, I adored the boldness of Julia Roberts, and wanted a man like Richard Gere, who would take my hand and spend the rest of his life with me.

In the 1980s and 1990s, most stories coming out of India were conventional, about men and women falling in love and having children. On the other end, I am in a constant dilemma about how the diversity which once existed in Manipuri society is now lost, and has been erased from Manipur’s history. Because of factors like globalisation, people have come up with very conventional heterosexual ideas around gender.

When I look back, in the 1970s and 1980s people were very progressive in terms of how they dressed and met each other. Now, people are embroiled in conflict due to nano-divisive politics. The recent situation has made this worse. The hills are dominated by the tribal community, which tends to be very strict about gender. People there can’t come out of the closet. Imphal as a city would provide a certain liberty of expression to people. Because of this conflict, there is more division than ever before.

Anindya: Niladri, can you talk about this one encounter Krishnagopal has with a boy, who asks him about ‘a disease that never leaves the body’? This dalliance between desire and disease reminds me of To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life by Hervé Guibert, where the author spoke about being diagnosed with AIDS. What impact did translating this part have on you?

Niladri: That’s a very rare part of that book, because things only get dark for a split second, before Krishnagopal gets back to his fun tone. The fact that he acknowledged it is important. We’re looking at a writer who is aware of a dark underbelly to his identity, but the fact that he doesn’t dwell on it, is also his politics. There is a certain heteronormative expectation from queer narratives to always be sad. A good queer story must be miserable, and the protagonist must die a terrible death. If society gets unhappy narratives of queer people, straight people can sit back and say, “Thank god, I’m not one of them.” But here’s this man in his late 50s, who says, “I’m gay and I think it’s bloody fun!” This defiance is what I got from Krishnagopal Mallick. He is creating a counternarrative to how homosexuality was seen for a long time.

He is aware of AIDS, but in spite of it, he refuses to feed into the narrative, instead opting for one full of joy, fun and sexiness. Another point I go back to, is how his narrative is not as much about love, but more about pleasure. I regard it as being anti-patriarchal too, because patriarchy tries to contain sexuality by sentimentalising it.

Anindya: True. We don’t want to get the narrative of ‘love is love’ dirty. Everything is sanitised and cleansed. On the other hand, Krishnagopal’s work is dripping with lust and it is so delicious. It is so important to mark lust just how one marks love.

Ideas of truth and home

Santa read an excerpt from her novel about the complicated feeling of home she tries to pursue amidst the political strife in Manipur

Anindya: Coming to you Santa, I’d like you to talk about the moral police, from whom you received multiple threats, and yet you keep pushing with your truth.

Santa: I want to be free of all oppression, and that makes me very vulnerable. Moral policing poses a real risk to my life, and I constantly get backlash from militant groups, because I have been very open and vocal about our struggles. People don’t want a person like me to talk about Manipur’s politics. They feel transgenders should be confined to beauty parlours. But I believe in coming forward and talking about several issues in Manipur. The dark side to this was that I was left alone to deal with this situation, even by the community. I wanted to get justice against the violence, but no one supported me. But there are also happy memories of the nights when the community mobilised itself and occupied the streets of Imphal. This community culture taught me a lot.

Anindya: The spectrum of gender nonconforming people have this organic lived life in the markets and bastis of Manipur, which really makes me want to invoke the spirit of home, which you beautifully talk about towards the end of the book. Could you share something about this feeling of home?

Santa: I had spoken against the mismanagement of Rs 10 lakhs which were supposed to be put down for transgender welfare. Because of this, I was attacked and the police even came to arrest me. I had to go to Bangkok to save my life. Despite the hardships, I believe that Manipur is a home to many communities, and no one can claim Manipur only for themselves. I wanted to see Manipur the way it used to be, where people from different communities lived together.

I also wrote about how the idea of home has been completely destroyed by the ongoing communal strife. The very idea of peace is poison, corrupted and polluted by tensions. People in power are throwing tantrums under the garb of restoring peace, and innocent civilians are left to deal with the situation. People have different understandings of home. My perspective comes from the lifelong experiences and collective efforts of our transgender society and culture. This is the capital we have invested through solidarity, support and networking.