On a particularly rainy evening in Kolkata recently, comfortably ensconced in the beautiful drawing room adjoining the terrace of the Glenburn Penthouse, Sandip Roy revealed that he reads “the dedication and acknowledgment section of a book with immense interest, sometimes even more than the book itself”. As such, the dedication in author Siddhartha Deb’s new novel, The Light at the End of the World, was of particular interest to him. “One part of it says that the book is ‘for all ghuspaithiyas [a slur, denoting intruders] everywhere, real and imagined, near and far’. Why is that?”

With this question, the tone was set for the latest Glenburn Culture Club conversation, one that promised, in authentic Siddhartha Deb-style, to push boundaries, broach difficult subjects and engage the audience deeply. “I would say that it is an act of solidarity,” said Deb. “I was trying to grapple with the whole idea of who ‘belongs’ or ‘does not belong’, in India and elsewhere. Because I’m a writer, I am struck by words and how they enter the currency and become acceptable – and while there were some people I wanted to thank, I did feel inspired to dedicate it to everybody who has been defined by this slur word.”

Why ‘real and imagined, near and far’? “I am not just critical about India; I am also critical about the United States,” replied Deb. “This book was finished in the Trump era. So, this dedication is about people who don’t belong; people who cross borders, sometimes for deeply desperate reasons. Moreover, this is a novel; it is interested in crossing all kinds of borders – genres, literal history, time.”

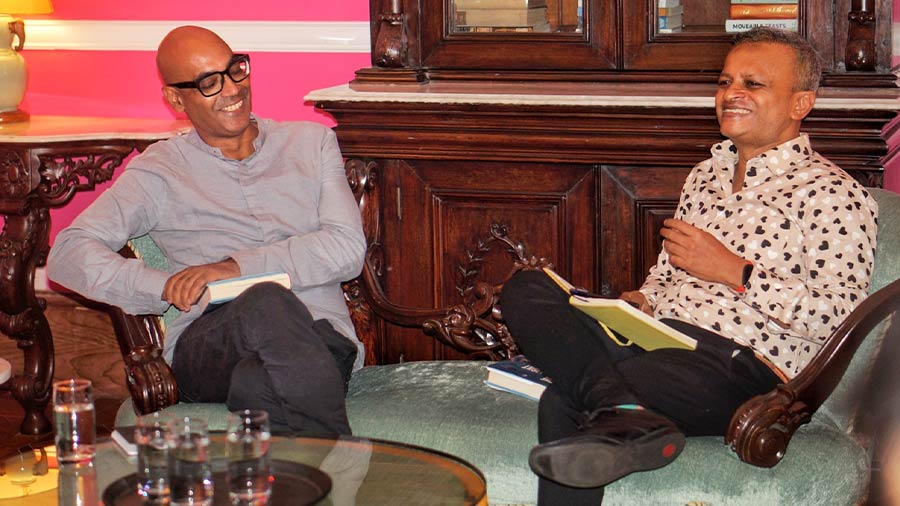

Members of the audience listen to Siddhartha Deb and Sandip Roy converse

‘Kolkata crossed with a bit of the occult, psychoanalysis, and theosophy’

Roy observed the multitude of timelines operating within the book, which is Deb’s first novel in 15 years: a dystopian New Delhi, in the time of demonetisation and digital surveillance; 1984 Bhopal, right before the Union Carbide gas leak; 1947 Kolkata, just before Independence, when communal riots are happening; and even 1859, right after the quelling of the first war of independence. Why did Deb choose these time periods from history?

“They were of particular interest to me both politically and aesthetically,” said Deb. “I was interested in 1984 Bhopal because I felt it had not been dealt with adequately. Again, 1947 Kolkata just before Partition has been written about a lot, but not in a way where the realism is crossed without the elements. I was also interested in the period after the sepoy rebellion of 1857. So while these historical moments and their cataclysmic violence mattered, I was also interested in storytelling possibilities – Kolkata and the Partition of Bengal crossed with a bit of the occult, psychoanalysis, and playing with theosophy.”

The conversation in full swing in front of a rapt audience at the Glenburn Penthouse

‘You will see a lot of my strange reading when you read this book’

It is this ambitious tying together of India’s socio-historical fabric with mysticism, mythology, and real-world events that sets this sweeping novel apart. In it, the characters are not connected by family or blood, but by a kind of experience of the uncanny and the haunted – “they are in each other’s dreams,” as Roy says. So there is Bibi, a former investigative journalist, tasked with tracing a former colleague who may or may not know alarming State secrets; in 1984, a mercenary is out to find someone who may be involved in a plot leading to the real-life Union Carbide disaster. In 1947, a veterinary student, Das, has been adopted by a mysterious committee to pilot a mythical Vedic airplane that might be the answer to the world’s problems; and in 1859, a British army officer has embarked on a journey to the home of an anti-colonial leader. The themes of how the supernatural and the occult mix with colonial and post-colonial realities, and how “small wars stitch together the fabric of the future,” run through The Light at the End of the World.

“You will see a lot of my strange reading, whether it is history or fiction, when you read this book,” Deb tells the audience. “There are many layers of questing taking place. As a writer, it also allows me to play with ideas.” He went on to tell the audience about how, after he finished writing the book, in which his character, Bibi, writes about detention centres in Assam, he was asked by a publication to ‘go to Assam and write a story’. “I remember texting my friend, a writer in New Jersey, about how creepy it was that I would now be visiting the place and going down the same highways that I had already described in my book,” recalled Deb. “There is a section in the book where Bibi is in a rented SUV going down towards the river valley. And here I was, following in the footsteps of my character!”

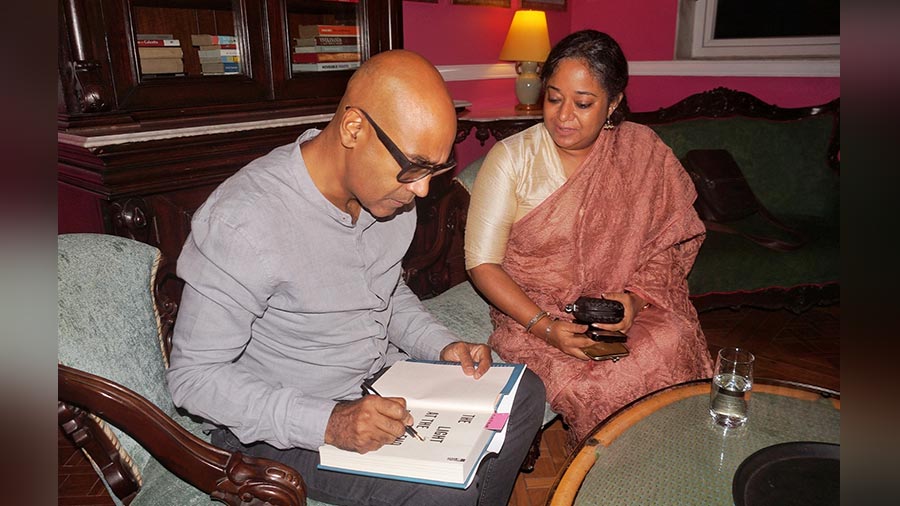

Karuna Parikh, in the audience, interacts with Siddhartha Deb

How much of what he saw in Assam match up to what he had imagined? “Reporting influences fiction, but I did not anticipate how fiction also influences reporting,” said Deb. He also recalled being on a reporting assignment in Assam two years ago, when a well-known leader descended to the fields from his helicopter and talked about the “ghuspaithiyas”. “He worked up the crowd with his incendiary speech,” recalled Deb, “and it was strange; he descended from the sky into the birthplace of Sankardev, a man of peace, and talked about hating the people who live in that very place! If you do that, you are the one who is ailing. And that’s the way my mind works — my novel deals with this kind of thing.”

‘When I write, I think I am smarter than in my everyday life’

The highlights of the discussion were when Deb read out two excerpts from this book — one from the section set in Delhi, the other from the segment pertaining to Bhopal. “I think fiction does have to play with both the conscious and subconscious,” said the author. “And when I write, I think I am smarter than in my everyday life. Writing is hard, as we all know; sometimes the answers come to you in dreams, and when you wake up, you think, ‘Yes, that’s the way it should happen’. It’s a creative thing, it’s an art.”

Deb signs copies of his book

Given the subject matter he often writes on, the stances he takes and the questions he asks, does he ever feel fearful? “It is always a tricky thing, but I have always been quite outspoken, particularly in my non-fiction,” replied Deb. “I have been doing journalism for a long time, and I have become concerned — now that I am doing footnotes for a non-fiction book, I found out that several of the people I have spoken to are now in prison, especially in Kashmir.”

“But I think, for me, it is important to take risks,” he says, in conclusion. “Otherwise, there won’t be any hope left.”