“Here’s your Barbie and Oppenheimer,” quips Suman Chandra, as we stand in front of Mauna Mukharata — a massive work of acrylic, charcoal, coal dust, mud, sand pen and ink on fine linen, created in 2023. It is one of Chandra’s newest artworks, but also the first to catch the viewer’s eye as they step into CIMA Gallery. This is, perhaps, fitting, for the stunning work of art bears the name of the exhibition as well — Silent Vision, Chandra’s first solo CIMA show after he won the fourth edition of the CIMA Awards last year. As the director of CIMA, Rakhi Sarkar, said at the opening of Silent Vision, “The CIMA Awards project was launched in 2015 for two reasons: one, to break the urban-rural barrier standing in the way of the visibility of art from all corners of the country, and two, to bring a practice of serious evaluation of art to India.” That rigorous process of evaluation has brought Suman Chandra to CIMA, and resulted in Silent Vision, on display at CIMA Gallery till August 19.

But what about the “Barbie and Oppenheimer” quip? It stemmed from something apart from the topicality of the two films; its significance lay in the curious – and brilliant – use of an overarching pink in a landscape of blackness, a vision marked by an absence of green. Chandra’s work, after all, is intricately tied to and informed by the politics, history and sociocultural impact of coal and its mining. It is a relationship of observation, lived experience, inspiration and research that began in childhood – his father was a small coal businessman in Midnapore – and solidified in 2015, when he began his Master’s degree and encountered coalfields for the first time at the Mugma colliery.

The artist next his creation, Mauna Mukharata (90 inches x 288 inches, acrylic, charcoal, coal dust, mud, sand pen and ink on fine linen)

It was this use of pink, in a landscape dotted with the darkness of a customary black, that led to a fascinating discussion about the intricacies of warm colour theory, in which the discovery of LED lighting went on to play a part in positing pink as the secondary colour to green. It was this use of pink, in its painstaking detail, that steered the conversation towards the complicated political history of the colours pink and blue, and how they came to take on their deeply gendered overtones in a post-industrialised world of synthetic dyes.

It was this use of pink, in its abundance in Mauna Mukharata, that highlighted its steadily dwindling presence in the rest of Chandra’s Silent Vision — a vision brought to life through his paintings, sketches, installations, sculptures, photographs and video montages.

Many strands, many stories

Indeed, the sum total of Chandra’s work on display at the exhibition bore testimony not just to his artistic vision, but to his deep engagement – emotional and intellectual – in the world he inhabited and the stories he wanted to tell. Some of these stories are colossal; they dominate entire walls, entire lives, entire existences – existences captured deftly by Chandra in the methodical grid-like mazes of representational maps and the pictorial conventions of mining (Niyamita Abadhyata 2). Other stories emerge in pockets, seemingly hiding the cracks of the blackness, yet telling a story of growth, resilience and shards of beauty in the midst of a shorn land (Prati – Beshi series).

And then there are the stories that bring to life the looming complexities of human interaction with this ever-changing landscape. A wounded landscape, scratched and bloodied (the Sthayi series); a landscape that exists because of human intervention, becomes the site of people’s suffering, and, interestingly, also their resilience, acceptance and continued, mundane engagement (Pelabata 10). “For land to be known as a landscape,” says cultural journalist Siddharth Sivakumar, “it has to retain a certain experiential independence through its vast barrenness, beauty, wilderness, or any of its other inherent qualities to the person exploring and appreciating it. In other words, when a land’s salient features – hitherto beyond the scope of the observer’s mundane experiences – are encountered for the first time, it triggers an aesthetic response in the viewer that bestows on the land characteristics of a landscape. The colossal mines of Suman’s paintings qualify as landscapes, for they, too, fall beyond our mundane experiences.”

A delicate balance of science and storytelling

Suman Chandra’s ‘Prabaha – Sanketa’ series, documenting and experimenting with the Sohrai art tradition

Perhaps the most searing exploration in Chandra’s study of this human-landscape relational story centres around its evolution in the traditional art form of Sohrai, practised by the generation of coal miners who migrated to Jharkhand in 1990. As Sivakumar says, Sohrai, which was originally found along the borders regions of West Bengal, Odisha and Bihar, “had its roots in the Hazaribagh region, where artists used natural and mineral colours for their paintings.” But the contingent nature of land politics and migration played a pivotal role in the changes in the landscape, not least of which was the disappearance of sources of grain and coloured soil that were integral to the art form.

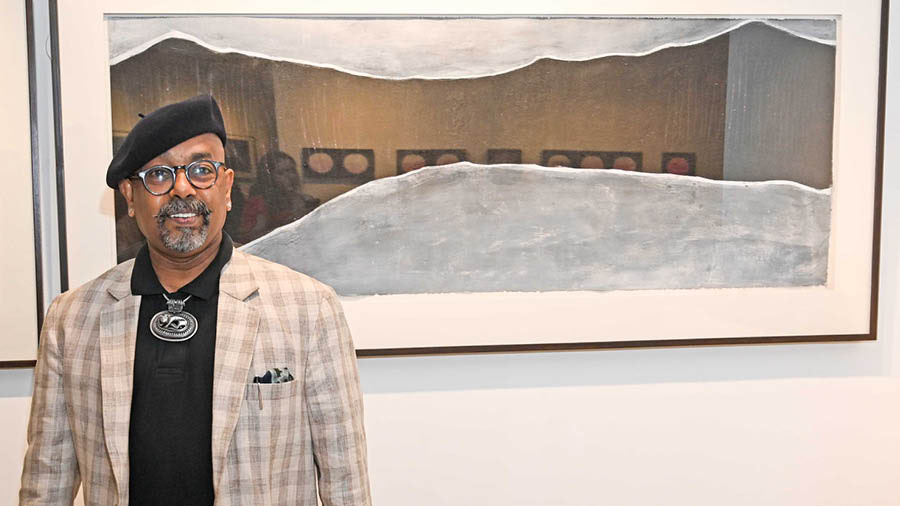

Renowned artist Paresh Maity at the opening of ‘Silent Vision’

Today, writes Sivakumar, “Sohrai relies on synthetic colours readily available in the market,” resulting in the new generation of Sohrai artists covering “the protruding palpable motifs of the older generation with garish artificial colours.” In a series titled Prabaha – Sanketa (charcoal on paper, exposed underground coal mine gas), Chandra’s artistic direction is distilled into a delicate balance of scientific enquiry and storytelling. He develops a unique process of image creation that is, at once, an ongoing experiment and a complete story — of transformation, of shifts in belief systems, of evolution/degradation. “As Suman documents the Sohrai tradition and pays homage to the colourful people lost at the margins, he also reminds us of the ever-threatening darkness of the coal mines by infusing the methane and carbon monoxide fumes into the image-making process.”

Tanusree Shankar admires Suman Chandra’s work at the opening of the exhibition

Focused research, wistful art

Ultimately, what Silent Vision offers the viewer is a blistering mix of the studied focus of a researcher, and the observational wistfulness of the artist and human being. Chandra takes on, and executes, a task of mammoth proportions – the task of depicting the overarching presence of the human hand in the creation and perpetuation of the coal landscape while also highlighting human marginalisation. There are almost no human figures explicitly depicted in his artwork – but the barely-acknowledged thread of human existence, persistence, suffering, survival, life, death, and even love, runs through the exhibits like a network of veins (Niyamita Abadhyata 1).

The artist silhouetted against the running landscape of the ‘Niyamita Abadhyata 1’ series

“There are many layers to the stories usually associated with such realities,” says Chandra. “And because of that, there are many different ways to look at, and tell, these stories.”