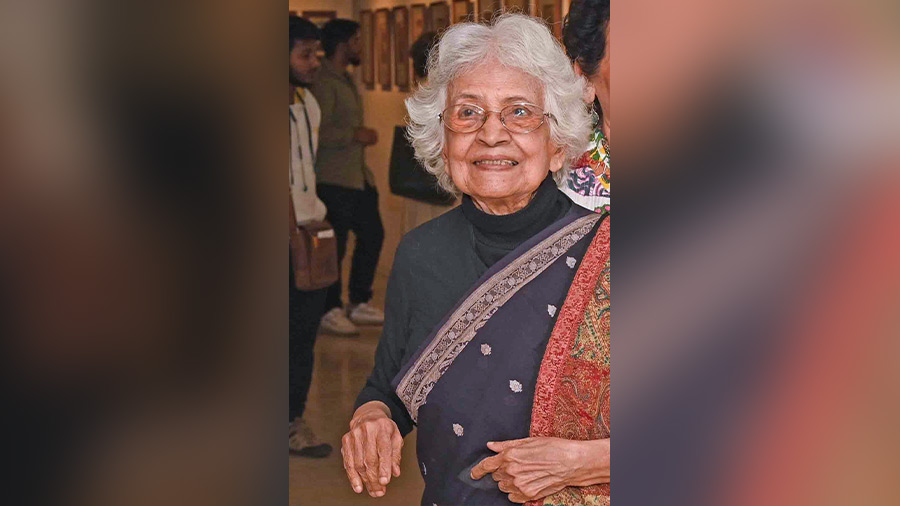

When Ruby Palchoudhuri sits with the weavers from Kalna, or the narrative scroll patuas from Midnapore, she communes in a down-to-earth fashion, speaking the lingua franca of revival of their skill, quality and design development. When she is in Paris, her language is fluent French, which sees her in sync with the cognoscenti of craft revitalisation. When she takes a break at her home in Gayabari, she is one with nature. And when she entertains in her Kolkata family house, rich in tradition, collectibles and rare books, where the crème de la crème descend, it is with the elegance of someone who has been a doyen of art and craft facilitation, an author of many significant publications on craft, curator of exhibitions across the globe, advisor and president emeritus of the Crafts Council of Bengal, and a vibrant presence in the renaissance of craft forms for many, many decades.

How many? At age 94, she is still busy. And ideating. Her energy enzymes are at a peak, her memory sparkles, and once you delve into the workshops, festivals, cultural exchanges and the range of craft from bell metal to the finest jamdani weaves, from clay forms to kantha and zardozi and the silver filigree of Moukhali, Sunderbans — where upping the ante is of prime importance — you realise the enormity of the revitalisation of the movement to preserve, promote and resuscitate our handicraft and textile heritage.

Where did it all start? Her initial years of homeschooling, where learnings included vocal and instrumental music and drawing, were a far cry from the Loreto College culture she went to thereafter. But it was art that the young Ruby Ghosh was to single-mindedly pursue, joining the Government College of Arts and Crafts, for five years, with eminent artists, such as Chintamoni Kar, Shanu Lahiri and Atul Bose (who did a portrait of her mother), around and then spending two years at the Chelsea School of Art. With her focus on graphic art, it seemed but natural that she would go into textile design.

She went into the study of the richness and variety of Indian textiles, realising that India had clothed the world starting from the 2nd century BC and the legacy had to be carried forward.

Somewhere along the way, her heart was stolen by the tall, handsome Monu, whom she married in 1957. He became her one true support to pursue her varied interests throughout her life. In 1959 she set up a block printing unit with traditional designs, popularising it in urban markets in India and abroad. Kabari, the first salon of its kind to introduce elaborate hairstyling and make-up was set up with Gosto Kumar. She was one of the six designers who pioneered leather-wear from India, taking it to Rome, where Gina Lolobrigida was to spontaneously exclaim “molto bene”! There’s more—the first air hostess saris for Air India were designed and printed by her.

Inspiration and application

Terracotta work in progress Shutterstock

The journey with the Crafts Council of West Bengal began in 1976, after the passing of Ruby’s mother in law, the well-known parliamentarian and founder-member, Ila Palchoudhuri. She donated their family land to settle migrant weavers in Phulia and Shantipur. Another big influence was Prabhas Sen, visionary, sculptor and technologist, who contributed to the revival of craft and textiles of the Eastern and North-eastern regions. But it was Ruby whose thirst for firsthand knowledge of the crafts of eastern India propelled her to travel to the rural areas to meet craftspersons in their homes and study their way of life to understand how they combined utility with aesthetics in their creative repertoire.

There could, of course, have been no better mentor or inspirational force than Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, founder of the World Crafts Council, the Crafts Council of India and all the regional councils. Post Independence, she formed the Handicrafts Board and travelled throughout the rural areas of India and brought about the revival of crafts, textiles and folk theatre. It was at her behest that Ruby was to visit all the craft centres in Bengal, reaching out to the locals who had the knowledge and skills.

Inspiration also came from American art historian Dr Stella Kramrisch, a pioneering scholar of ancient Indian art and architecture. Ruby met her in 1985 and requested her to mount the famous Mahamaya exhibition in 1986 at the Port of History Museum in Philadelphia. On Kramrisch’s passing, the Philadelphia Museum of Art organised an exhibition of the kantha pieces she had collected. Ruby was accompanied by craftspersons Pritikana Goswami and Bina Dey and had them demonstrate the art of quilting.

Aditya Malakar was one of the 12 participating artists at this exhibition and his exquisite demonstration of sholapith drew wide applause. He went on to many cities in the US and on his return, trained many young craftsmen in his village to pursue what is a thriving craft today.

Ruby’s interest in Indian crafts took her to Britain to study Indian collections in British museums. Later at Yale, her fellowship saw her researching Indian crafts, illustrations and paintings documented by British Indian artists during the colonial period.

Standout initiatives

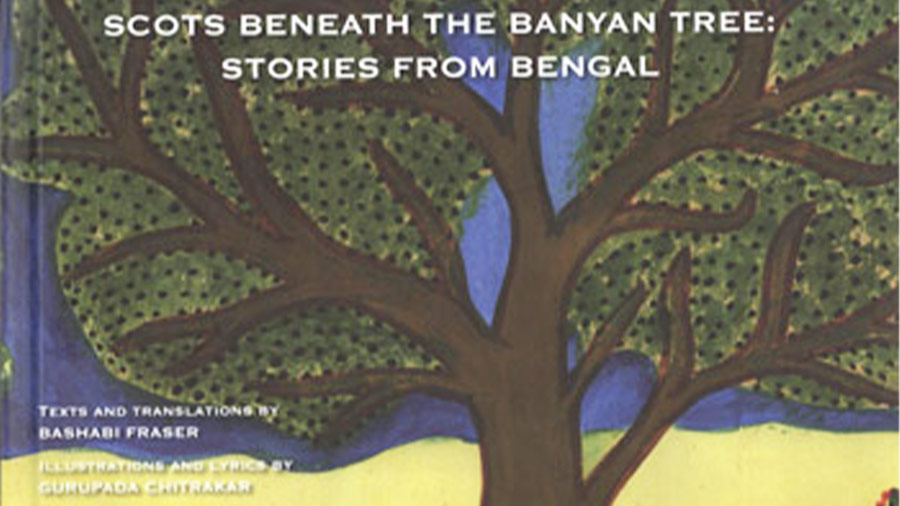

Book cover of 'Scots beneath the Banyan Tree' Shutterstock

Ruby’s efforts of empowerment and engagement have seen a vast set of initiatives. One major success has been the resurgence of muslin of a very high count and introducing Jamdani weaving technology in West Bengal. Master weaver Jyotish Debnath has been a driving force. Other crafts that have got traction are metal casting using the cire perdue or lost wax method that has produced excellent figurines and jewellery; creations in clay and terracotta, wood carving, basketry and finely woven mats, puppetry, stone carving, mask making, buffalo horn and shell jewellery and silver filigree ornamentation, patachitra and plenty more.

Ruby’s large contribution to the revival of Baluchari came from her initial encounters with Kallu Hafiz in Benaras. He was the only one who used the jaali technique — the Naqshbandi craft that originated from Bukhara.

To celebrate the 75th anniversary of British American Tobacco, ITC commissioned her to make a 15 foot by 12 foot panel that was woven in Benaras, with a full backing in gold using Baluchari motifs and techniques.

Some of the international exhibitions are a standout. There was the Arts of Bengal and Eastern India by the CCCB at the Commonwealth Institute, Kensington High Street, London, in 1982. The brochure brought out for this became a collector’s item, with the cover designed by Satyajit Ray and a collation of articles by experts. The British public got to view a wide variety of eastern India’s handicrafts on an unprecedented scale, culled by connoisseurs who personally visited the villages and rural craft centres. Eight master craftsmen demonstrated a wide variety of craftsmanship, including textile printing and sitar making, daily. The renowned sculptor Meera Mukherjee was present and Jamini Roy’s works were a special attraction.

Voices and images

Between 1995 and 2007, a most engaging “Durga Jatra” took place. Of Creating the Goddess. Nemai Chandra Pal from Krishnanagar was the main sculptor. The closing ceremony at Peabody Essex Museum in Massachusetts had the towering presence of ambassadors Siddhartha Shankar Ray and J.K. Galbraith. The Durga project moved to Scotland, then to Cardiff in Wales, and went all the way to Sydney, Australia, with the last leg in Honolulu.

At the British Museum, the Goddess was part of the Voices of Bengal. The presence of Gurupada Chitrakar added a new dimension to it all, as he was guide, storyteller and artist all rolled into one. Witnessing the craftsmen at work, added the extra drama during which they had the drummers in unison, ending with the immersion in the Thames.

Gurupada worked in close association with Ruby’s Crafts Council. Invited to participate in the Scottish International Story Telling Festival in Edinburgh, he worked on a book titled Scots beneath the Banyan Tree. It chronicled nine Scotsmen who had contributed in various fields in India, interleaved with reproductions of scrolls of the life stories of Scotsmen such as David Hare, Ronald Ross, Alexander Duff and the Yales, as well as a brief history of patuas by Ruby and an introduction by Charles Bruce. It was translated by the well-known academic Bashabi Fraser, CBE. Ruby recounts Gurupada entering the hall where the original scrolls had been hung and bursting into a song: ‘Aami Kon Deshete Elam’! His scroll on Roxburgh, the botanist, was bought by the Royal Botanical Gardens.

Ruby’s French connection is notable. Inspired by Christine Bossennec, an interpreter of Tagore, who started the Alliance Française in Kolkata, Ruby joined the organisation in 1951. She became chairperson of the student body, and then a prominent committee member. In the early days, she took part in plays by Moliere and other dramatists. Her active collaboration with the Alliance Française through workshops, cultural exchanges and exhibitions and promoting artistic and cultural ties between India and France were recognised by the French government, which conferred on her the Palmes des Arts, the Palmes Academiques and a personal medallion received from President Mitterrand.

To celebrate the bicentenary of the French Revolution, a festival organised with 50 scroll painters of Bengal saw them painting and singing the stories of the French Revolution in their own style and language. Palchoudhuri had gone to the patuas, telling them the story of the French revolution, without showing them any visuals. A charming set of interpretations emerged where Marie Antoinette looked like Durga, and Louis 16th looked like Shiva and the guillotine like the trident!

Eminence grise

So many other tales of engagement emerge from the repertoire of Ruby, plucked from a razor sharp memory. Like the massive Damaru festival of traditional theatre and theatre crafts of eastern and north-eastern India at the ITF Pavilion in 1989, with 150 participants. Or the presence at the Osaka National Museum of Ethnology, where a 35-foot high chariot of Lord Jagannath was shipped after being constructed and dismantled in Kolkata. Along with fishing boats, including catamarans. And one must mention Ruby’s fascinating in-depth article titled NEEL (Indigo), with pertinent illustrations interspersed with poetic references, historical facts and notes on Vaishnavite connects, cultivation, value of neel as a dye and the Neelambari weave, particularly from Shantipur.

When you see her in her eminence grise stature with her silvery coiffeur, and at the peak of forever activity, with her vibrant persona, possibly clad in a Neelambari baluchari to match the feminine mystique (her own words from NEEL), the Lifetime Achievement Award being conferred by CIMA Gallery (on December 24 at Taj Bengal), which completes 30 years of its existence is a fitting tribute to this woman of substance and stature. Who reiterates that it is not just expositions that impact, but also the idea of income generation, the uplifting of quality, the marketability of the crafts designed, upping skill sets and achieving the goal of excellence in the use of crafts in our daily lives as a measure of building a sustainable society.