Fussy babies need to be rocked, and often. A babe in arms, swaddled tightly in soft cotton, swayed gently, held side-saddle in the nook of a hip, with murmured refrains from half-forgotten nursery rhymes queuing behind the lips of a tired caregiver. Merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily… until sleep softly comes, and the fussy baby lies still.

Often, you come across a second category — even fussier babies that need to be rocked… by rock. I occupied pride of place in this arena of difficult children, much to the disdain of my parents and the dust that collected on the How To Put Your Demon Child To Sleep cassettes they bought me. The only pacifier I tolerated to lull me to dreamland was their collection of jazzy-rocky-poppy music from yesteryear. From Billy Joel’s whispering piano and Elvis Presley’s tranquiliser of a voice, all the way to a timeless and genreless Dean Martin giving way to some Frank Sinatra, the strangeness of baby me’s needs would plaster a proud smile on my father’s face — his infant daughter was writing the first chapter of her autobiography as a musician. It seems to flow in her blood!

It has been a quarter of a century since I was rocked to sleep as a child. Today, the only music that flows through me is from my phone and into my ears. While music may not have been the string that weaved a career for me, it certainly made itself felt as a thread that holds and connects. Something that has kept my family together in more ways than one.

I found myself standing at Aquatica… waiting for one of our connecting strings to take the stage

It came as no surprise, then, that the moment Bryan Adams announced that his ‘So Happy It Hurts’ tour was coming to Kolkata, our family group chat blew up with demands to purchase tickets “absolutely immediately, do NOT delay or you will get thrashed by my firm parental hand”. After some tech-convincing (“Ma, the QR wristbands will work, we don’t need printouts of anything”) and some geographical squabbling (“please, Papa, Google Maps is not lying to us”), when the evening of December 8 finally arrived, I found myself standing in the middle of the ground at Aquatica, taking in the sights and smells and sounds of my first- ever concert, triangled by my family, waiting for one of our connecting strings to take the stage — larger and louder than life.

While we are a ‘genre-no-bar’ family when it comes to music, English soft rock holds, well, a soft corner in our hearts. Many a fight has been dissolved through a love for music, whether it be Cliff Richard’s voice echoing from the drawing room, luring my sour self sheepishly out of the shadowy confines of my bed, or the opening chords to Johnny Cash’s Ring of Fire inciting sparks of recognition between my brother and my father at a crowded dinner party. I have hazy memories of happiness bouncing around in the pit of my stomach when we sang the lyrics to We Didn’t Start The Fire in their entirety to an awed audience at Tollygunge Club.

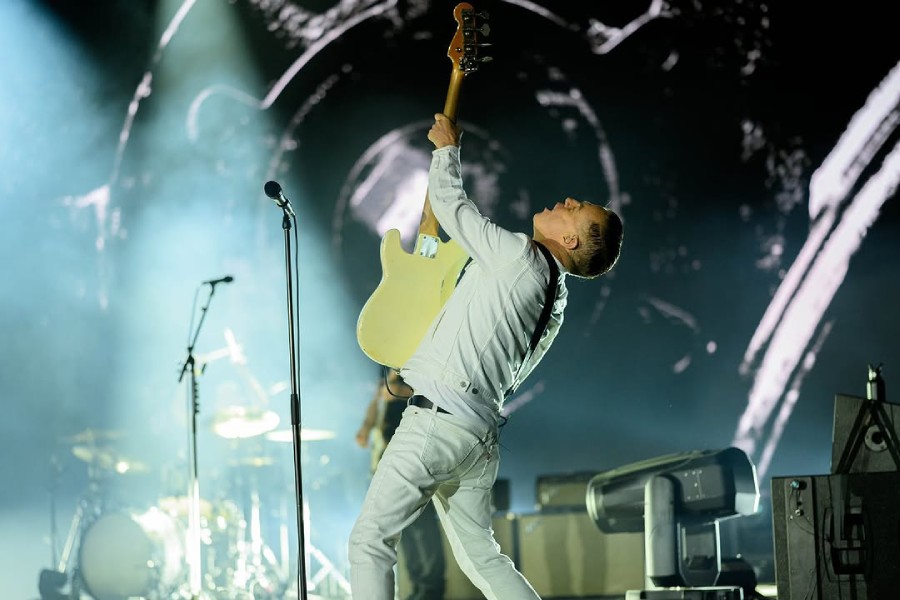

Come Aquatica on Sunday evening, the stage was set, not just for Bryan Adams but, it seemed, for my family, too. The lights danced their synchronised dance, spluttering and fading away, engulfing Adams into darkness for a few seconds. A spotlight shone on lead guitarist Keith Scott. A hush fell over the crowd — even the air knew that something good was coming. Gently, quietly came the opening bars of (Everything I Do) I Do it For You. Right on cue, my father, my brother and I turned towards my mother to catch a glimpse of the tears that had welled up in her eyes, threatening to spill uncontained, as she swayed to lyrics that took her down memory lane.

Four wheels of a car, with a guitar strum for a chassis

The author with her brother, Raunak Courtesy Aashera Sethi

The concert itself was an explosion of sound and spirit. Adams’s unmistakable voice carried through the cool night air, each note somehow familiar yet electrifying in its live rendition. Scott’s guitar solos were masterful, stirring the crowd into a collective rapture. Adams engaged with the audience with a charisma that only decades of performing could hone, regaling us with anecdotes and humour that felt intimate, despite the thousands in attendance. When Summer of ’69 finally erupted from the speakers, the crowd turned into a single, swaying mass of voices chanting the chorus like it was stitched into their DNA. Even my 11-song limit didn’t matter anymore — the energy of the evening had swept away any need for familiarity with the setlist. We danced, clapped and laughed — a family among so many, yet isolated in our bubble of joy.

As the concert wound down with All For Love, I looked around at my family. My father was singing unabashedly off-key, my mother was smiling like she hadn’t in years, and my brother, usually too cool to express too much, was caught rhythmically tapping his feet. That moment washed in blue, standing firmly on my square foot of grass, jostled rhythmically by a sea of strangers, is one where I felt that musical string tug and tighten itself around us. Four wheels of a car, with a guitar strum for a chassis. With minds and thoughts of our own, voices both on the ground and in our heads were soothed by notes old and familiar as an armchair. The Kolkata air, greeted by the first wave of winter, cut like a knife, nestling in our hearts.

That indefinable connection that turned a few hours of music into a memory of a lifetime

The concert was a reaffirmation of the ties that bind the author’s family, an echo of the shared memories and emotions Courtesy Aashera Sethi

The drive home was quieter than expected, the adrenaline replaced by a contented glow, each member of our little family lost in their own thoughts, humming the wispy remnants of the evening. As the night deepened, so did our realisation that the concert was more than just an evening of entertainment. It was a reaffirmation of the ties that bind us, an echo of the shared memories and emotions that music has helped preserve. In the end, it’s not the setlist or the venue we’ll remember, but the feeling — that indefinable connection that turned a few hours of music into a memory of a lifetime.

I don’t know if or when I will have children, but until then, I hold out hope — a hope that takes flight straight from my heart, that some day I can pass on to the generation after me a little bit of what our parents gifted us. From the soft hiss of an A and B sided cassette with spools of tape twisted around sore fingers, to a live and unfiltered voice echoing through the Aquatica sky, my familial wheel of a connection with Bryan Adams seemed to have come full circle — not just as a fan, but as part of an unassuming family whose threads will always be set to music.