Light, camera and action — these three words encapsulate the world of Satyajit Ray. Oxford Bookstore, Park Street, recently played host to a discussion on the auteur’s life and times to gain a deeper understanding of that world.

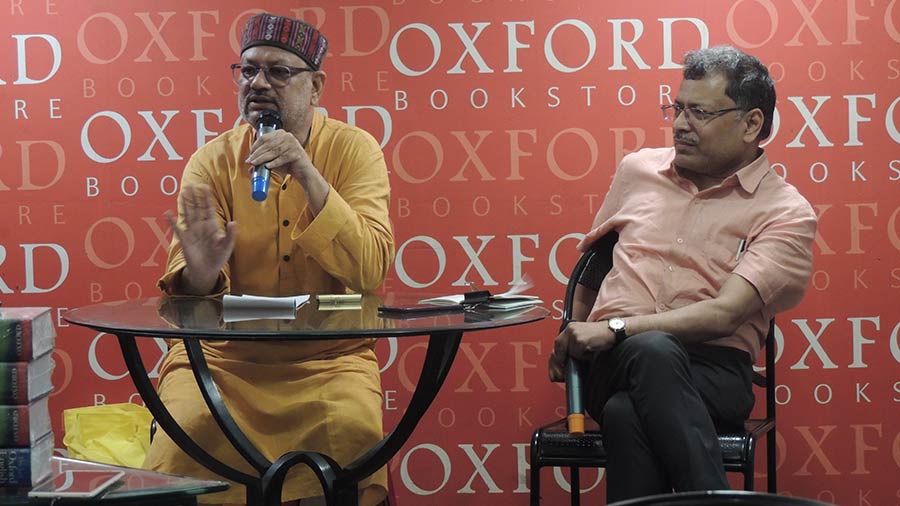

As part of the seventh edition of Apeejay Bangla Sahitya Utsav (ABSU), Debashis Mukherjee, an authority on Ray, and Somen Sengupta, a corporate bigwig and a researcher, on August 5 discussed different episodes of the legendary filmmaker’s life to debunk many controversies and untruths surrounding him.

Victim of social media syndrome

Highlighting how youngsters and even adults can be influenced by false information on social media, Mukherjee said such canards about Ray and other famous people were usually promoted by an amazing number of likes and upvotes.

Pointing out gross errors is fruitless as speaking against specific comments will not serve the purpose and instead increases the reach of such posts, he noted.

Mukherjee also said the spread of misinformation and the kind of popularity it generated had made it necessary to create a single forum that would contain the actual truth by exploring the life and works of Satyajit Ray.

The hero and the actor

Citing some criticisms of Nayak, starring Bengal's matinee idol Uttam Kumar, Sengupta recalled that a journalist was baffled as to how a superstar could travel by train and get recognised only by women and not a single male passenger.

“In that movie, Uttam Kumar, playing the role of Arindam Mukherjee, was travelling to Delhi to receive the national award in 1966. He was in a first-class coach — a category that was almost out of reach of most upper- and middle-class people back then. Arindam is a matinee idol, which suggests that his large following is made up of women, who frequent movie theatres in the afternoon,” explained Mukherjee, in response to the statement.

The expert on Ray said the focus of the movie was entirely on the inner workings of the superstar’s mind. “Ray never intended to belittle the actor. It’s clear in the sequences where Arindam argues with his senior, stating that the actor is not a mere puppet, an opinion held by movie legends like Humphrey Bogart and Marlon Brando.”

The neutral bystander or the compassionate sympathiser?

A student of Presidency College and Santiniketan, Ray had witnessed the Partition in 1947 and the famine and the great riot that came on its heels. Outlining these events, Sengupta said some critics had expressed disappointment that Ray’s movies did not capture the turbulent times of his youth.

In reply, Mukherjee said any debate must be based on the works that an artist has actually produced and not on what he could have produced. “There were some renowned contemporary directors, such as Ritwik Kumar Ghatak, who had themed their movies on the turbulence of the ‘40s and perhaps that led Ray to figure out that it was not his strength.”

“It’s also possible that Ray did not experience the trauma of the Partition or other tragic events to the extent that the others did,” he explained.

Vision through the lens

Speaking about the difference between the language of cinema and literature, Mukherjee said Ray had initially wanted to create a community of knowledgeable moviegoers. “It’s unfortunate that even now our critics mostly concentrate on the plot of a movie and nothing else. Ray believed that the task of the director was to highlight the aspects that were not there in the originals.”

He explained further that just as a writer would depict a scene or a character with his words, a filmmaker’s job was to do the same with visual techniques and other available means such as dialogue, incidental sounds and even music. “After this comes the transition of scenes as a lot depends on that too.”

“It’s a cardinal error to watch Ray’s films and compare them to the original literary works. Ray had adapted the plays and stories to suit the language of cinema. Maybe years later from now all those who study his creativity would be able to discern the subtle techniques that he used to translate his thoughts into a cinematic presentation,” said Mukherjee.

The audience at the event. Saurav Roy

Slanders and Sikkim controversy

“It was once alleged that Ray was reluctant to give Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay, the author of Pather Panchali and Aparajito, his due respect. It’s totally wrong. Ray prepared a one-reel documentary on the great writer which was to be shown before the movie. He also created a booklet that had major sections on Bandopadhyay, but it had to be curtailed as it failed to find favour with then chief minister Bidhan Chandra Roy,” Mukherjee said.

Ray was harsh on critics who had tried to point out ‘flaws’ and ‘discrepancies’ in his films. “The failure of his critics to be able to discern the subtle nuances of his screenplay bothered Ray and he had often responded to their accusations in rather strong terms.”

In the 1970s, Ray made a documentary on Sikkim at the insistence of Sikkimese monarch Chogyal’s American wife Hope Cooke. It was meant to be a promotional film for Sikkim as a tourist destination. In that documentary, a lavish celebration is shown in the royal palace, followed by a scene where poor people were eating the leftovers thrown out on the streets. It was daring on part of Ray to keep the scene in a film funded by the monarch himself.

“The film was never shown in Sikkim. It was edited and Ray’s original version does not exist today. In 1975, then Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi used military strength to bring Sikkim under India’s control. Then Ray’s film, funded by the Sikkimese monarch, led to a conflict of interest and Sikkim was banned,” said Mukherjee.

Never playing it safe

Many critics say that apart from Two, a short film produced by a US company, Ray never came forward to share his views on the explosion of American brands and US imperialism.

“The 12-minute short film was part of a TV programme that contained a sitar recital by Pandit Ravi Shankar and a puppet dance. It was shown at a time when the Vietnam War was on. Through this movie Ray made a bold statement against the US aggression even when he was making it with US money,” said Mukherjee.

“This wasn’t the only occasion when Ray demonstrated his strong character. David Selznik, a famous American producer renowned for his large-scale productions, faced the brunt of Ray’s unflinching morality when he chose to present Selznick Golden Laurel to the Indian director. Selznik was in the habit of preparing notes for the awardees on what they were to say while receiving the awards. Ray, however, coolly ignored the note and went ahead with his own speech,” he noted.

“Selznik also asked Ray to direct a film with his company and sign an agreement before leaving. In reply, Ray said that he only worked on projects that were signed in his house and in his drawing room. No doubt Ray’s was an imposing personality that could dwarf one of the richest persons in the world. It was Ray at his best,” he added.

Beaten but not bowed down

Ray’s two Hindi language films, Shatranj Ke Khiladi and Sadgati, drew the ire of certain communities and did not do well at the box office. Acknowledging that, Mukherjee said caste issues and Mumbai movie industry politics were to blame for such failures.

“To shoot Sadgati, Ray had chosen two villages in Raipur — one was of the Dalit community and the other one was of upper castes. Those in the latter village were afraid that Ray’s depiction of the cruel reality would put them in peril. The discomfort remained largely confined to the local press of the area. Besides this, the Madhya Pradesh Chalachitra Nigam stood solidly behind Ray on this controversy,” he said.

“Even Doordarshan was hesitant to show the movie on television. It was largely because of parliamentarian Ashok Rudra that the matter came to be debated at the national level and that paved the way for it to be aired eventually. Sadly, the film was not shown in Raipur, the place of the shoot. While the nation watched Sadgati, a different movie was shown in Raipur at exactly the same time,” he told the audience.

Shatranj Ke Khiladi, too, faced a lot of difficulties on account of the opposition of the Mumbai lobby. “It was almost impossible to see the movie in Mumbai and only a morning show could be arranged in one theatre. Scathing reviews made the rounds across media houses; Ray’s screenplay was ridiculed and criticised, mostly for the weak portrayal of Nawab Wajed Ali Shah. What they all failed to see and acknowledge was how Ray depicted the takeover of Indian territories by the British,” said Mukherjee.