In a home theatre-driven age, the usual response to a musical gig is getting a microphone, a couple of Sonodynes, an amplifier system and pretend that one is Arijit.

Our Musical Mornings WhatsApp group showed a complete poverty of common sense in proposing that we dispense with the mic, sing in the open, call every T-D-H to join and send ‘love’ emoji messages to each other about the good time we all had.

Why it wouldn’t work

Of course, it wouldn’t work for various reasons.

One, the WhatsApp group members voted to descend on Rabindra Sarobar on winter mornings, a location where the National Green Tribunal had thrown musicians out with their drumstick, cymbal and guitar on the grounds that the melody was affecting bird, tree and fish health. It was only a matter of time then that someone would turn up and demand ‘Where is your written permission to spread a durrie and sing songs of love under an autumn tree?’

Two, you can’t just ask Sarobar walkers to interrupt their programmed 55-minute constitutional with a ‘Mann re tu kahe na dhiir dhare’ at 7.23am. Most would confess ‘Bahenji, abhi aaya’ and walk brisker.

Three, why would anyone seek to stir the air with melody when they — or anyone — could hear the same stuff on YouTube using noise-cancelling speakers?

Four, why would anyone with an arthritic knee bother standing for a couple of hours (in the wake of RS authorities refusing the odd plastic chair in) to listen to all they would have heard before anyway or could easily sample the original in their drawing room?

The initiative succeeded despite everyone prophesying, ‘What a waste of time!’ Mudar Patherya

These are the four reasons why the Sarobar music engagement should have miscarried. Now look at why this initiative succeeded despite everyone prophesying, ‘What a waste of time!’

Why it did work

We drew in — much against what most anticipated — outstanding singers. Laparoscopic surgeon Dr Kallol Banerjee could move from Bhupen Hazarika to Manna Dey to Kishore Kumar while, head down, continue to extract strains out of his 1964 harmonium. Law student Additiya Mukherjee had a voice as slender as a hair strand. Ananda Basu is a lawyer by day but crooner by morning. Dr Madanki probably hums Madan Mohan in her mind when advising patients on fertility. Srabanti Basu is our resident tabalchi-cum-singer. Put them on a stage with some reverb and the first reaction would be ‘Amateurs?’

Laparoscopic surgeon Dr Kallol Banerjee accompanied the singers on his 1964 harmonium Courtesy: Mudar Patherya

We began to enforce the singing rule; any jogger who even politely slowed in our direction to pick a line or two between pants would be virtually pounced upon: ‘Aashun, asshun! Boshun. Ki gaiben bolun?!’ Most victims hung around perplexed out of sharm and lihaaz; after the fifth song, the same aforesaid jogger, would have, sweat mopped, burst into an impromptu RD/ Bappi.

We praised like paid flatterers. The result is that the ex-bathroom singers realised they were not being sniggered at. That is when they attempted their first bandish in decades with the casually scattered line of ‘I sang in the school concert in 1973 and was given a merit card…’

We didn’t have a batting order so to speak; singers were encouraged to jump the queue. Even before ‘Purano sei diner kotha’ had wound down, someone was raising her fisted hand to the mouth, clearing her throat and preparing to launch Auld Lang Syne onto an unsuspecting audience.

We didn’t have an emcee to navigate song flows; anyone could interrupt (and did) and lead the singers into a different direction so that for the next eight seconds people were singing three different songs at the same time.

We didn’t laugh at people who didn’t get it right. I grated when an attendee recited Kabhi Kabhie (the non-diluted Sahir version that needs to be comprehended with an Urdu-to-English dictionary) by transposing every ‘Z’ with ‘J’. In my book, a sin. But there was no getting away from the fact that he maxed 10/10 for memory. In any conventional mehfil, the purists would have called for a spittoon; at the Sarobar, we gave aali-jaan a sitting ovation.

We made friends. The same gentleman (J&Z) who we had never seen before his astonishing Sahir delivery, turned up the following Sunday with an offer we couldn’t refuse: would we care to do one of our baithaks in the cinema hall he owned? A few minutes later, mobile numbers were being exchanged and he had been inducted into the inner circle.

We provided a platform to characters. One of them happened to be the 79-year-old Kanta Verma, settled in Kolkata from Meerut. One would have expected the young lady to sit tight-lipped in the corner (‘Main to bas sunnay aayi hoon’ types). She developed an unusual repertoire: couplets to suit every mood; jokes to match every moment. The result was that as soon as a song petered out and before the next one began, the audience would turn to her: ‘Kantaji koi Meerutwali suna deejiye.’ And true enough, she would respond with ‘Ek baar aisa hua…’ as if whatever she was about to relate something autobiographical. We weren’t just turning to her to fill spare moments; we were celebrating her.

One rule: no rules

We maintained one rule: no rules. The result is that Gulu Balani reached out for the harmonium and sang a tribute to wife Shilpi on the 40th anniversary of their marriage.

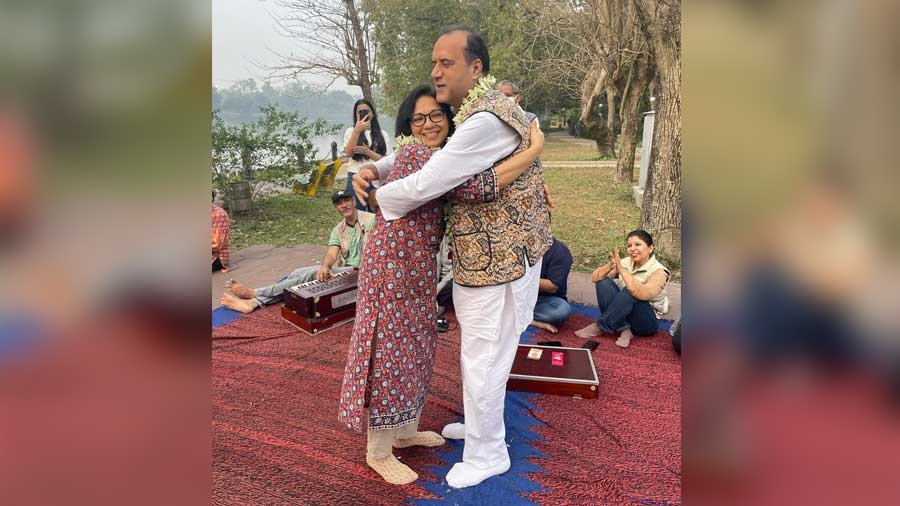

If you think that this is where it would have ended, then wait: Gulu-Shilpi turned up the following Sunday morning with chai and singharas for the group in gratitude for the ‘break’; the rest of the group turned to a bag in the corner and produced garlands; Gulu-Shilpi exchanged garlands and hugged each other in public view while the harmonium player (Dr Kallol Banerjee who had trained under Kalyanjibhai, no less) feverishly produced a tune that sounded like a shehnai cousin.

Gulu Balani exhanged garlands with wife Shilpi, on the 40th anniversary of their marriage

After all these ‘business details’ had been done with, there were non-song details to enhance the song. The mist. The mellow fruitfulness. The ducks. The slowing rowers. The competing bird song. The ‘green green grass of home’.

'Mission statement'

Then I heard the most preposterous thing at our last Sarobar session. These fellows are planning to get themselves invited to Deshbandhu Park (right across the city) where they intend to sit in the open and sing with their north Kolkata equivalents. Not as in a competition; as in a collaboration. And that done, they intend to move to Salt Lake the Sunday thereafter, after which, based on the momentum of the narrative, they expect to turn up in Howrah. Then Baruipur, then Batanagar, then Kankurgachi, who knows. ‘Create one large pan-Calcutta community of amateur bathroom singers,’ they said, almost sounding like a mission statement.

Ridiculous, I said. And then I remembered. It had happened before when someone had suggested ‘Sarobar’ as an acoustic music destination. A line by shaayar Shamim Jaipuri flashed past: ‘Zamaana ehle-khirad se to ho chuka maayoos. Ajab nahi koi deewana kaam kar jaaye.’