“It was entirely out of my interest in education that I started writing the book since the idea of secularism was entirely different then from what it is now,” said Sarojesh Mukerjee, whose new book The Life and Times of David Hare: First Secular Educationist in India, was launched at the Oxford Bookstore on December 6.

Published by Niyogi Books, the book traces the journey of David Hare as an educationist and his contribution to making education truly secular in India. The author was in conversation with Rosinka Chaudhuri.

Amit Chaudhuri delivers the opening address

Author Amit Chaudhuri was present at the book launch and delivered the opening speech. “I’m delighted that this book is out. I’m sort of taken with the idea of this book about David Hare. We don’t know enough about history, our modernity, our city, the emergence of the modern in this city. I’m also delighted because the author is Sarojesh and I am particularly fond of him,” said Chaudhuri.

Keeping the Christian missionary influence out

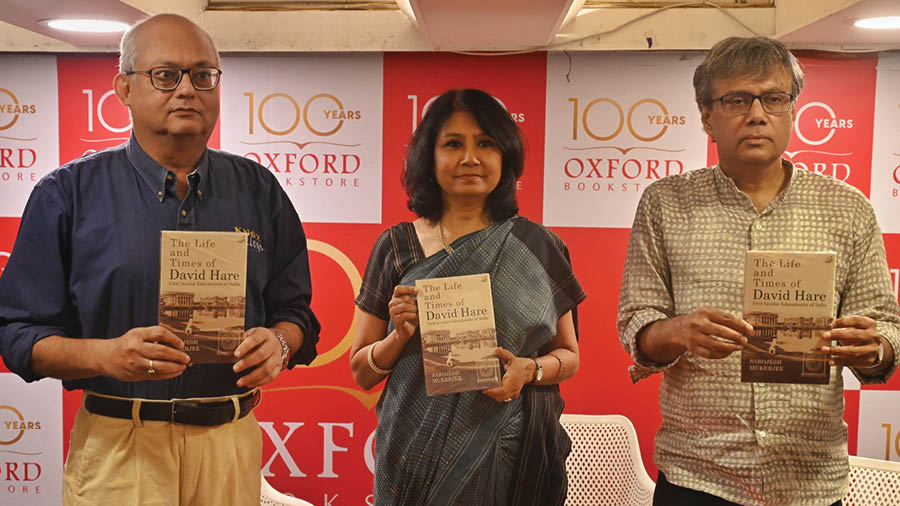

Sarojesh Mukerjee at the book launch

Explaining the secular stance of David Hare, Mukerjee remarked that secularism primarily meant keeping the Christian missionary influence out.

“The first organised schools in Bengal were opened by missionaries like William Carey, William Ward, and Joshua Marshman, who were primarily missionaries and then educationists. And of course, there were other indigenous schools, which were mired in religiosity. So David Hare kept the Christian missionary influence entirely out and reconciled different shades of Hindu opinion,” explained Mukerjee.

Profit was always above governance

However, the British initially did not want to spend on education in India as that would have entailed substantial expenditure on part of the government.

Mukerjee pointed out that there were three other reasons for this. “First, the British presence was completely dependent on their military presence, which was insignificant compared to the size of the Indian population. So they wanted to avoid any confrontation along these lines and also did not want to interfere with Indian education, which at that point in time essentially meant Sanskrit and Persian education.

“The second reason for which they did not want to interfere was that they were into the conciliation of Hindu and Muslim elites. So while Hastings would go out and sponsor the Calcutta Madrasa for the benefit of Muslims, or the East India Company would also sponsor the Hindu College in Benaras for the benefit of Hindus.

“And the third reason is that the East India Company was both a merchant and sovereign. In this dual role, the role of the merchant and the sovereign was Indian governance,” he elaborated.

The audience at the book launch

‘Illuminating and educative’

The conversation steered toward how Hare established Hindu College against all odds and the programme ended with a lively Q&A session with the audience. Amit Chaudhuri who was present throughout found the discussion to be particularly “illuminating and educative”. “We continue to benefit from these discussions. I would have wanted to know more about the different shapes education takes as this discussion seemed like it was defined by Hare’s dislike for Christianity,” signed off Chaudhuri.