A blue wave stopped by a yellow wall. A billion dreams dashed by 11 men in canary uniform. The player of the tournament collecting his prize like a letter of termination. Disappointment, despair, even disbelief, as Australia beat India in the ICC Men’s Cricket World Cup final. Not just beat, but battered and bettered India in all the departments of the game. It happened first on March 23, 2003, at the Wanderers Stadium in Johannesburg. On November 19, 2023, with redemption, even revenge, on the cards at the Narendra Modi Stadium in Ahmedabad, it happened all over again. For an entire generation that grew up with the heartbreak of 2003, history repeated itself, not as farce, but as another tragedy that will haunt countless Indians for countless days. Perhaps none more so than Rahul Dravid, the only man to be on the losing side on both occasions. First as a player, then as coach. For Dravid, the parallels would be clear, but before we get to that, there were also differences.

The biggest difference being that, unlike in 2003, India entered this year’s final as the favourites, as champions elect in a home World Cup that they had dominated even more comprehensively than Australia 20 years ago. There was also a marked difference in atmosphere. At the Wanderers, there may have been a few thousand more Indians than Australians. But, in the cricketing colosseum of Ahmedabad, as Harsha Bhogle pointed out, “we are present in the stands in proportion to our population as countries”. But the differences only reinforced the excellence of two Australian outfits designed to play big games. Nervelessness is coded into their DNA, if such a thing even exists for a collection of individuals. Pat Cummins’s troops, just like Ricky Ponting’s men, arrived at the clash to settle all clashes and did not flinch. In doing so, they dictated the course of a one-sided final that had much more in common than just the result.

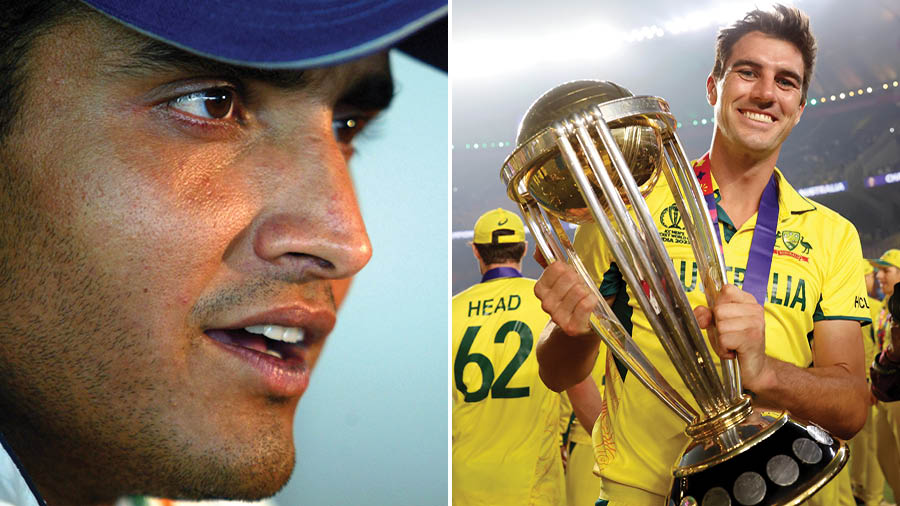

Surprise, surprise at the toss

Sourav Ganguly and Pat Cummins made unexpected calls at the toss with contrasting results

When Sourav Ganguly chose to bowl first on a pitch expected to be batting-friendly in 2003, the decision went against convention, maybe even common sense. Why not just get runs on the board in a final? But Ganguly was right, for there was cloud cover at the toss, the threat of rain (which duly arrived later on in the game) and ample swing and spin in the wicket. Just that the Indian bowlers never turned up to back their captain, having succumbed to the stage before they could succumb to their opponents. In putting India in on a far warmer day on a far slower pitch, Cummins also went against convention and, perhaps, common sense. But Cummins gambled on there being dew at night, on the pitch easing out for the batters under lights and, most importantly, on his bowlers nailing their plans. What Ganguly was denied in 2003 was given to Cummins in 2023, as the Australians did not miss a beat with the ball and in the field.

Rohit Sharma on the charge, a la Virender Sehwag

Virender Sehwag and Rohit Sharma batted in the finals as if operating in their own parallel cricketverse

Rohit Sharma has always been an anomalous graduate of the Mumbai school of batting. Not just for giving the impression that time slows down to 0.5x when he is at the crease, but also for his glaring lack of footwork. In other words, he is all hands and eyes, something Virender Sehwag can relate to from back in the day. And it was this hand-eye coordination that threatened to take the momentum away from the Australians in two separate finals. As the rest of the Indian batting lineup struggled to get going, Rohit and Sehwag batted in their own parallel cricketverse. Rohit’s 47 off 31 may not have lasted as long as Sehwag’s 81-ball 82, but it was punctuated by the same intent of taking the game to the Australians. However, in both cases, the downfall of India's boldest batters came down to a sensational piece of fielding from a somewhat unlikely source. In a team packed with Ponting, Andrew Symonds and Michael Bevan, the outstanding fielding effort came from Darren Lehmann, whose deadly throw hit the stumps to run Sehwag out. Similarly, in spite of David Warner, Glenn Maxwell and Marnus Labuschagne lining up for Australia, it was Travis Head who made the most telling fielding contribution by sprinting back and lunging forward to take one of the catches of the tournament and send Rohit on his way.

The dismissals that stunned a nation

Sachin Tendulkar and Virat Kohli got out in the finals after misjudging the pace of two seemingly innocuous deliveries

Prior to their respective World Cup finals, Tendulkar and Kohli knew that barring a miracle, they would finish as the top run-scorer of the 2003 and 2023 editions, respectively, setting a new benchmark for consistency at the highest level. But that benchmark and its place in history was the last thing on their minds when they made the long walk back up the steps of the Wanderers and the Narendra Modi Stadium, 7,546 days apart. In 2003, Tendulkar departed after underestimating the pace of a short ball from Glenn McGrath, pulling it into the air and into the obliging hands of McGrath. In 2023, Kohli departed after overestimating the pace of a good-length ball from Cummins, dragging it on to his stumps instead of guiding it to third-man. Two of the most decorated batters of their generation (or any generation) had misjudged the pace and lost their wickets to seemingly innocuous deliveries. In the seconds between Tendulkar and Kohli trying to make sense of their dismissals and walking off, an entire nation was stunned into silence.

Two match-defining partnerships, led by two career-defining knocks

Ricky Ponting and Travis Head turned on the style with scintillating centuries

Two partnerships proved instrumental in the two World Cup finals and both came for Australia. In 2003, Ponting and Damien Martyn added 234 runs for the third wicket, taking Australia to an unassailable total of 359. In 2023, Head and Labuschagne combined for 192 runs for the fourth wicket, taking Australia to within two runs of victory. While Ponting was the aggressor with a swashbuckling century in Johannesburg, it was Head who stole the headlines in Ahmedabad. For their part, Martyn and Labuschagne, quintessential Test batters, relished their roles of playing second fiddle, content to let the guy at the other end do the tonking. Ponting’s 12 boundaries in 2003 had been smashed with a sense of carefree disdain, as if he had strolled out for a swing at a picnic. Head, who had to deal with a shaky start from the Aussie top-order, batted with a similar gusto, hitting 18 boundaries during his second innings of a lifetime in less than six months, having already hammered the Indian bowling at the ICC World Test Championship final in June.

Out of ideas, out of spirit

The winning moment from the 2003 and 2023 finals

By the time 30 overs had been completed in the second innings of both finals, the outcome was not in question. It was a matter of when, not if. In 2003, it was the second ball of the 40th over that put India out of their misery and sealed Australia’s third world title. In 2023, it was the last ball of the 43rd over that handed Australia their sixth World Cup crown, drawing the curtain on an unforgettable campaign for India in more ways than one. The final hour or so of play in both contests had been reduced to little more than a formality, with the Indian players going through the motions, out of ideas and out of spirit. There was nothing left to fight for barring some last-ditch honour. There was the admission that India had been outplayed by a team that rose to the occasion in a way the Men in Blue had not. There was the anguish that many in the Indian squad would not return to play another World Cup final. As it turned out, six Indians — Sehwag, Tendulkar, Yuvraj Singh, Harbhajan Singh, Zaheer Khan and Ashish Nehra— came back for one last shot at glory in 2011 and seized the day at the second time of asking. From fallen heroes, they retired as world champions. Some more may join them in their redemptive arc from 2023, but even if they do not, they will remain heroes all the same.