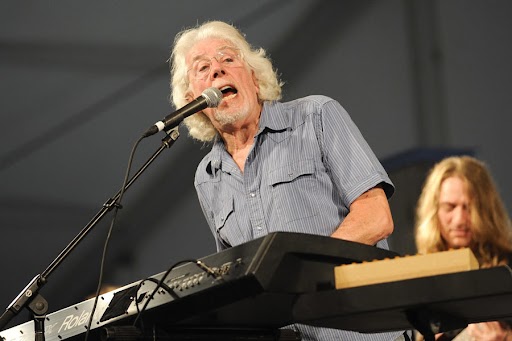

John Mayall, the pioneering British bandleader whose mid-1960s blues ensembles served as incubators for some of the biggest stars of rock’s golden era, died on Monday. He was 90.

The death was confirmed in a statement on Mayall’s official Facebook page. The statement did not give a cause or specify where he died, saying only that he died “in his California home.”

Though he played piano, organ, guitar and harmonica and sang lead vocals in his own bands with a high, reedy tenor, Mayall earned his reputation as “the godfather of British blues” not for his own playing or singing but for recruiting and polishing the talents of one gifted young lead guitarist after another.

In his most fertile period, between 1965 and 1969, those budding stars included Eric Clapton, who left to form the band Cream and eventually became a hugely successful solo artist; Peter Green, who left to found Fleetwood Mac; and Mick Taylor, who was snatched from the Mayall band by the Rolling Stones.

A more complete list of the alumni of Mayall’s band of that era, known as the Bluesbreakers, reads like a Who’s Who of British pop royalty. Drummer Mick Fleetwood and bassist John McVie were also founding members of Fleetwood Mac. Bassist Jack Bruce joined Clapton in Cream. Bassist Andy Fraser was an original member of Free. Aynsley Dunbar would go on to play drums for Frank Zappa, Journey and Jefferson Starship.

In his book “Clapton: The Autobiography” (2007), Clapton described playing in the Bluesbreakers under Mayall’s tutelage as a demanding but rewarding kind of musical finishing school. After leaving the Yardbirds and joining the Mayall band in April 1965, “grateful that someone saw my worth,” he wrote, he moved into “a tiny little cupboard room at the top of John’s house” so that he could better soak up all the lessons he wanted Mayall to teach him.

“With long curly hair and a beard, which gave him a look not unlike Jesus, he had the air of a favorite schoolmaster who still manages to be cool,” Clapton recalled. “He had the most incredible collection of records I had ever seen,” and “over the better part of a year, when I had any spare time, I would sit in this room listening to records and playing along with them, honing my craft.”

The one album that Clapton recorded with Mayall, “Blues Breakers” (1966), is often credited with kick-starting the electric blues boom of the 1960s among young Americans and Britons. With songs by Robert Johnson, Otis Rush, Freddie King and Ray Charles, as well as Mayall himself, the album provided a repertoire, arrangements and a thick guitar sound that would be widely copied by hundreds of bands in both countries. In 2003, Rolling Stone magazine ranked “Blues Breakers” No. 195 on its list of “The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.”

John Mayall was born in Macclesfield, England, just outside Manchester, on Nov. 29, 1933. His father, Murray, who played guitar in local pubs and collected records, and his mother, Beryl, stimulated his interest in music, but he trained as an artist and graphic designer at the Manchester College of Art and, after doing military service in Korea, worked for several years for advertising agencies. (He would later put that experience to use by designing the covers of many of his albums.)

Mayall was already 30 when he decided to become a full-time musician and moved to London, where performers like Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies had already carved out a niche for the blues. Financially, it was tough going: Even when he had future stars like Clapton, Green and Taylor in his band, the Bluesbreakers followed a grueling routine of touring by van and playing short engagements on cramped stages in small clubs, often for audiences of only a few dozen people.

But after guitarists everywhere took notice of the “Blues Breakers” album and its equally influential follow-up, “A Hard Road” (1967), featuring Green, Mayall’s horizons expanded. He started touring regularly in the United States and Europe: “The Diary of a Band,” a two-disc set recorded live in the Netherlands and other locales with Taylor, was released officially, and performances at the Fillmore West and in Germany and Italy eventually circulated in bootleg versions.

In 1969, after recording the album “Blues From Laurel Canyon” and befriending members of the American blues band Canned Heat, Mayall moved to the Los Angeles area, where he lived for the rest of his life. That led to a fundamental shift in the composition of his bands, with British musicians giving way to Americans.

His first “American” group included Harvey Mandel on guitar and Sugarcane Harris on electric violin. Later units featured guitarists Sonny Landreth, Walter Trout and Coco Montoya, all of whom went on to successful solo careers.

Mayall had already begun moving away from what Clapton called his “textbook blues” style before coming to the United States, forming the jazzy, drummerless acoustic band that recorded “The Turning Point” in 1969. In the 1970s, however, he would go deeper into, as the title of a 1972 album put it, a “Jazz Blues Fusion,” working with jazz musicians like trumpeter Blue Mitchell and saxophonists Ernie Watts and Red Holloway.

But Mayall never abandoned the blues altogether, and in the 1980s he re-formed the Bluesbreakers, with which he would continue to tour and record, with constantly shifting personnel, well into the 21st century. In some editions of the band, he was joined by alumni like Taylor and McVie; Clapton would occasionally play with him as well.

In all, Mayall released more than 70 albums, the most recent of which was “The Sun Is Shining Down” (2022). He also issued several DVDs, including one of a 70th-birthday concert in 2003 at which he was joined by many of his most prominent former sidemen.

He is survived by his children, Gaz, Jason, Red, Ben, Zak and Samson; seven grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren. His two marriages ended in divorce.

It was announced in April that Mayall, along with his fellow blues artists Alexis Korner and Big Mama Thornton, would receive this year’s musical influence awards from the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

In 1979, a fire destroyed Mayall’s house in Los Angeles. Lost in that blaze was most of the record collection that had so impressed Clapton and other blues initiates, which by that time had grown to include thousands of discs, including many rare 45 and 78 rpm blues singles, as well as many of the live tapes Mayall had made of his own bands in the 1960s.

In 2014, Mayall sat down for an evening-long interview at the Grammy Museum in Los Angeles, in which he reminisced about the challenges of being a crusader for the blues in London in the early 1960s. He recalled playing 11 shows a week in “dens of iniquity” and having to persuade McVie’s parents to let their son, who was underage at the time, join his band.

“It was extremely exciting,” he said of those times. “We all felt we were part of the same family and that we really were connecting with people, a new generation of people, and also having a great time playing. You just continually played; it wasn’t worth going home.”

The New York Times News Service