That winter afternoon we couldn’t spot a single tal or palmyra tree in Taltala, a central Calcutta neighbourhood, named after the Asian palmyra palm. We, as in myself and Suranjan Midde, who teaches Bengali at Rabindra Bharati University and is also an enthusiastic chronicler of stories of another Calcutta.

More than two-and-a-half centuries ago, the British did away with the palmyra groves; only the name stayed. The late P.T. Nair, often referred to as Calcutta’s “barefoot historian”, had once told me that Taltala used to be part of cosmopolitan Calcutta. Its demography comprised Muslim sailors, Anglo Indians, Baghdadi Jews and native Bengalis, both Hindus and Christians. Later, many European priests and nuns too arrived when churches such as St Teresa’s Church, Lord Jesus Church, St Anthony’s Shrine and Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity were founded in the area.

Midde is my guide for the afternoon. His friend, the sitarist Ustad Melvyn Anthony Lalit Gomes, lives in Taltala. We are to meet him that day. On the way, we go past several houses with nameplates that read “D’Costa”, “D’Rosario”, “D’Cruz”… “Bengali Christians with Portuguese surnames,” says Midde.

In his book on Dom Antonio de Rosario, a 17th-century Christian preacher of Bengali origin, Midde talks about the Bengali Christian community of Atharo Gram, a cluster of villages near Dhaka in Bangladesh. They were encouraged to embrace Christianity by Dom Antonio, according to Midde.

After Partition, many of them migrated to Taltala. Some of them settled down in different pockets of Bengal — Ranaghat, Krishnanagar, Thakurpukur, Taherpur — and some eventually moved out of India.

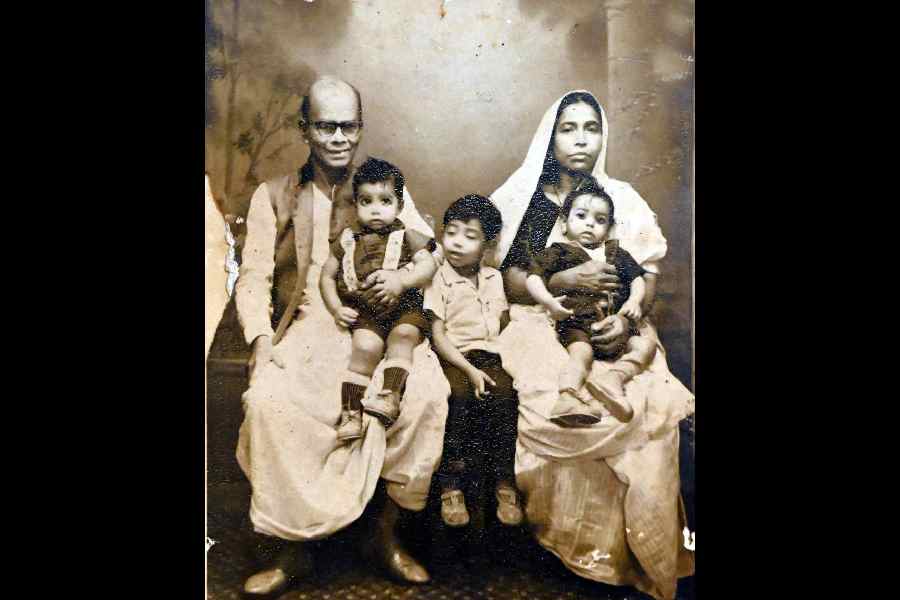

A picture snapped on the terrace of the Gomes’ family at Taltala in 1969. John Andrew Gomes and Agatha Gomes with their grandsons Melvyn Anthony Lalit Gomes (right), Theotimus Sushanta Gomes (middle) and Henry Sandip Gomes. Courtesy: Lalit Gomes

Son of a rich Hindu landlord of Jessore, Antonio was kidnapped by Portuguese pirates and taken to Arakan (now Rakhine, in Myanmar) to be sold as a slave. But he was rescued by a Portuguese priest, Manoel de Rosario, who raised him as his son. The boy embraced Christianity and took the nameDom Antonio de Rosario. Like his foster father, he too became a missionary.

A brilliant orator and writer, Dom Antonio is credited with being the writer of the first Bengali prose titled Brahman-Catholic Sambad. He is also said to have brought thousands of lower-caste Hindus and Muslims into the Christian fold.

Says Midde, “Since he was a liberal padre, he didn’t force the converts to forsake their native culture.” It was he who encouraged them to accept Portuguese last names and leave aside surnames that would not let them live down their caste history. None of this went down well with the Church authorities of the Augustinian order of Lisbon, in Portugal. They were against his method of conversion, and disowned him and his converted community as “lesser Christians”.

Our little excursion happened during Advent; Bengali Christians refer to it as Agomon Kal. One could smell Christmas in the air as we wound our way through the lanes. Some young boys were found making star-shaped lanterns with bamboo strips, paper and LED bulbs. Choirs practised agomoni gaan, or songs of Advent, and Bengali carols. “Ananda ananda mohananda bhai/Orey aar bhoy naai bhoy nai/ Probhu esechen dhoronitoley… Rejoice, rejoice, let’s all rejoice/Cast off all fear/ For the Lord is here...”

Finally, we reach Gomes’ residence. Lalit’s grandfather John had moved to the area from a village called Bandura in Atharo Gram in the 1920s. Lalit tells a curious tale about how Gomes Sr, who worked in a private company in central Calcutta, was attracted to the sitar. “One day as he walked past Ustad Enayat Khan’s Park Circus home, he heard him giving sitar lessons. Moved by the ethereal tune, he went in and requested Ustadji to accept him as his pupil,” says Lalit. Ever since, the Gomes family has come to be connected to the Imdadkhani gharana that specialises in musical instruments such as the surbahar and sitar and is named after Ustad Imdad Khan.

Sitar continued to strum through their lives, through generations. John’s son Benjamin Gomes was a disciple of Ustad Vilayat Khan and Lalit himself learnt first from his father, and then took his lessons from Vilayat’s younger brother Ustad Imrat Khan. Benjamin performed — both as a sitarist and an actor — in Satyajit Ray’s film Jalsaghar. Lalit’s son Benjamin Allen has picked up the sitar and his daughter Angelina plays the guitar. That makes them fourth-generation artistes.

Taltala’s distinctive history permeates its socio-religious practices and the mindset of its inhabitants.

It has also shaped its culinary traditions. Lalit’s wife Anjana is prepping for the grand Christmas lunch as well as seasonal goodies. It is no different for her sister Veronica Gomes, who lives in Hasnabad, one of the constituent villages of Atharo Gram. Between Anjana and Veronica — who is roped in via video call — they list the pre-Christmas and Christmas fare. Several types of pithe, a kind of sweet dumpling. Pakon made from ground moong dal and rice flour; chitoi or ashke pithe, which is a rice pancake eaten dipped in khejur gur or date jaggery; bhaja puli pithe, which is a rice flour dumpling with coconut filling.

Bhaja Puli Pithe with rows and a sail in caramel syrup made by culinary director of Joseph Uttam Gomes. Courtesy: NIPS Institute of Hotel Management, Kolkata

The Portuguese, among the first European traders to discover the sea route to India in 1498, introduced a variety of fruits and vegetables in this country. Potato, tomato, green chillies, corn, papaya, pineapple and even guava were brought to India by them. They taught the locals the art of making cheese. They also introduced a unique fusion of Western and Bengali cuisine.

Chef Joseph Uttam Gomes, who is culinary director of the NIPS Institute of Hotel Management in Salt Lake, too traces his origin to Taltala as well as Atharo Gram. He talks about “pudim”, which is actually improvised rice pudding. Gomes speaks with pride about some of the distinctive savoury items too. The vindaloo is different from the Goan or Portuguese versions. Its marinade comprises sirka, a vinegar made from fermented date palm juice, it is cooked in mustard oil and seasoning constitutes hot chillies. He describes in detail a dish called bhaja curry that contains slices of eggplant, broad beans and pangash fish.

There are many Facebook groups related to Atharo Gram, wherein among other things members exchange recipes. It is food that connects them and also those who return to Taltala from their adoptive homes in the US, West Asia, Canada, the UK and Australia during Christmas. Molina Vincent Mitra, a social worker in Taltala, says, “We are actually Bangal Christians. Our community has come a long way since Partition.”

To think none of it would exist if one little boy had not got waylaid by pirates.