If this were a film, I would say, play it backwards. Watch the whole thing in rewind mode, much like how it streamed in old video players. Backwards from the night of the sickle moon, blame game, allegations, arrest. Go well before heartbreak and Discovery. Keep moving back, jump decades, past this jubilee and that. Watch them fly, news reports from the 2000s, 1990s, 1980s with headlines such as Mushik Muktir Poth Khunjchhe R.G. Kar, Infection risk in R.G. Kar OTs, Chakri Niye Tughlaqi Kando, Silent protest awaits PM Rajiv Gandhi, Calcutta’s ‘worst’ hospital, No hostel for women students, Junior doctors to continue relay hunger strike… Gently land in Calcutta and Bengal of the late 19th century. Then, play.

***

The RG of R.G. Kar Medical College and Hospital was a physician named Radha Gobinda. He was born in 1852 in colonial Bengal, some years before Nil Ratan Sircar, his more famous peer and the “NRS”of the other medical college of Calcutta.

It was that point of the century — Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar was a young man, Raja Rammohun Roy had been dead for two decades, the Marquess of Dalhousie was Governor-General of India, Mangal Pandey would have just about joined the 34th Bengal Native Infantry and Rani Rashmoni was still building the Dakshineshwar Kali Temple.

Calcutta was the bed of diseases aplenty, but there were not enough hospitals. There aren’t enough today.

Unlike Nil Ratan, Radha Gobinda was born into a wealthy family. His father Durgadas Kar taught at the fairly new Calcutta Medical College. “He taught materia medica,” says Projit Mukharji, who teaches history at Delhi’s Ashoka University. Mukharji has written the book Nationalizing the Body: The Medical Market, Print and Daktari Medicine.

The government order by which the Calcutta Medical College had come up in 1835 specified that “the benefits of the college shall be open to all classes of native youths between the age of fourteen and twenty… provided they possess respectable connections and conduct”. There were, of course, class, economic and gender barriers. There were caste, religious and social barriers too. Those who finally made it found themselves up against a language barrier — at the Calcutta Medical College, the lessons were in English. Continues Mukharji, “Pretty soon they started conducting classes in Hindustani and Bengali. But there were no textbooks, only lecture notes. Durgadas was one of the first to write medical textbooks in Bengali.” His first work was Bhaisajya Ratnavali.

“Durgadas made money essentially as a writer and publisher of medical textbooks,” says Mukharji. He also helped set up the Mitford Hospital in Dhaka.

This was Radha Gobinda’s family background, one of money, privilege and education.

The family home was — and still is — in Howrah, but forget the Howrah Bridge, even its precursor of a pontoon bridge had not been thought up when Radha Gobinda was growing up. He attended the Hindu School. By some accounts, he used his father’s horse-drawn carriage for part of the journey and thereafter took a boat ride. For his son’s convenience, Durgadas built a house in Shyambazar. In time, Radha Gobinda too wanted to study medicine, and was even set on going abroad, except that his father didn’t grant permission. And so, he joined the Calcutta Medical College.

There is no one comprehensive account of Radha Gobinda. The best one can do is piece together a portrait from scraps of information. For instance, we know that he married young. We know he was into fitness and bodybuilding as a young man — Durgadas had built a gym in their home. We also know that he was interested in the stage, though it was his brother Radha Madhab who was a professional actor.

In Binodini Rachana Samagra, scholar and archivist Devajit Bandyopadhyay cites from legendary stage actress Binodini’s autobiography wherein she talks about “the well-known physician Radha Gobinda Kar” acting in the National Theatre without pay. This love for the theatre too, according to Bandyopadhyay, was a legacy of Durgadas.

More scraps of information: Radha Gobinda’s wife died. He married again, but around the time of this tragedy he found himself in the middle of an incident that led to his arrest. By some accounts, his studies suffered, which is when Durgadas stepped in and took control. The next thing we know is that Radha Gobinda left for Scotland. This was most likely 1883.

At the University of Edinburgh, Radha Gobinda’s friend was Ashutosh Mitra. “He went on to become the chief medical officer of Kashmir,” says Mukharji. Radha Gobinda returned to India in 1886 and received his medical degree a year later. In this avatar, he is a more focused, if not an altogether changed, man.

Nandini Bhattacharya,who is an associate professor in South Asian history and history of medicine at the University of Houston, Texas, US, tells The Telegraph that R.G. Kar discovered that cholera toxins originated in water.

The 19th century was now inching towards its end, but the medical scene in Calcutta was not vastly changed from the time when Radha Gobinda was a student. Immediately upon return, along with some other Bengali physicians he formed a society. It was here that they floated the proposal to set up a private medical school, which would turn out to be Asia’s first such institution.

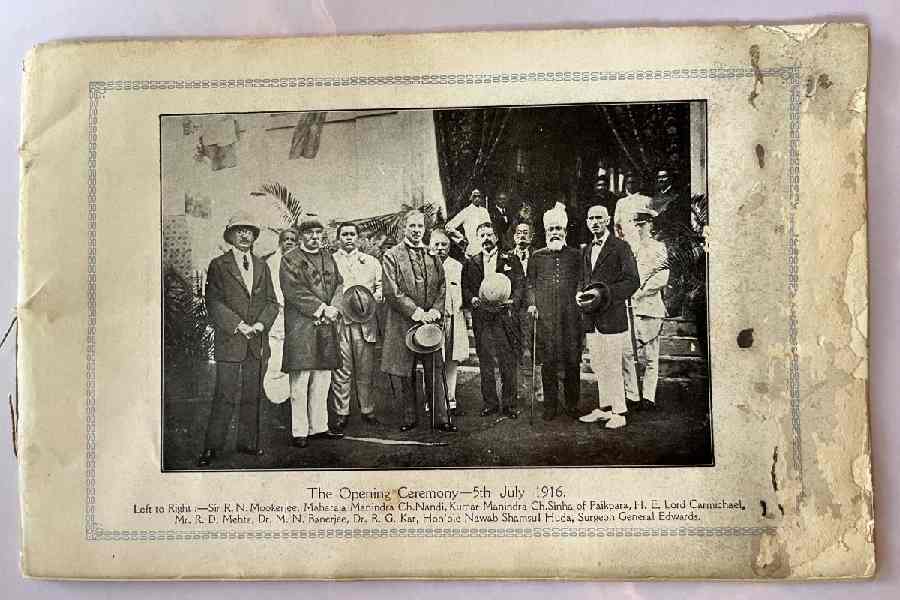

The Calcutta School of Medicine was R.G. Kar Medical College and Hospital’s name at birth. Over the years, it shifted location, changed names, grew a hospital, merged with Nil Ratan Sircar’s medical school, became the Belgachhia Medical School and upon inauguration by Lord Carmichael, who was governor of Bengal from 1912 to 1917, became Carmichael College.

“It was a private college, outside government purview, and the medium of instruction was Bengali,” says Mukharji. The founders might have been motivated by nationalism but that did not mean they were without business sense. “It was a private venture that was intended to make money,” says Mukharji. Unlike the institutions run by the British government, here, the top administrative posts were held by Indians. The longest serving head of Carmichael College was Nil Ratan Sircar.

Like his father, Radha Gobinda continued to write — titles such as Dhatrishohay, Anatomy, Plague, Gynaecology — and publish medical textbooks. Those too earned revenue, most of which was used to further develop and upgrade the institution. There are varied scattered accounts of the pains he took to raise funds for the institution till his death in 1918.

The Triennial report on the working of hospitals and dispensaries in Bengal: 1938, 1939, and 1940, notes that “medical education up to the standard of the M.B. Degree of the Calcutta University and M.M.F. Diploma of the State Medical Faculty of Bengal” was given in only two medical colleges of Bengal, Calcutta Medical College and Carmichael College.

In 1948, 30 years after Radha Gobinda’s death, Carmichael College was named R.G. Kar by the premier of West Bengal, Bidhan Chandra Roy. A decade later it became a government college.

***

Stop. If you are still somewhere between the late 19th and mid-20th century, you could be feeling a little disoriented from the time jump. You moved back, but it feels like progress. And if this is what happened before, then, what is the word for what is happening now?