The late Utpal Dutt, legendary actor-writer-director-activist and avowed Communist, wrote a play Barricade in 1972, depicting Adolf Hitler’s methods of coming to power in 1933. Unable to win adequate numbers at the ballot, Hitler is shown blatantly adopting undemocratic means to defeat his opponents, the labourers’ party, comprising Communists and their allies.

Dutt, who believed in using theatre to spread his political views, had written Barricade to draw attention to what was happening in India at the time; and it was not difficult for Bengali viewers to spot the parallels. The methods being used in violence-ridden Bengal of the 1970s to quell protests by Left labour unions were similar to what Dutt showed on stage.

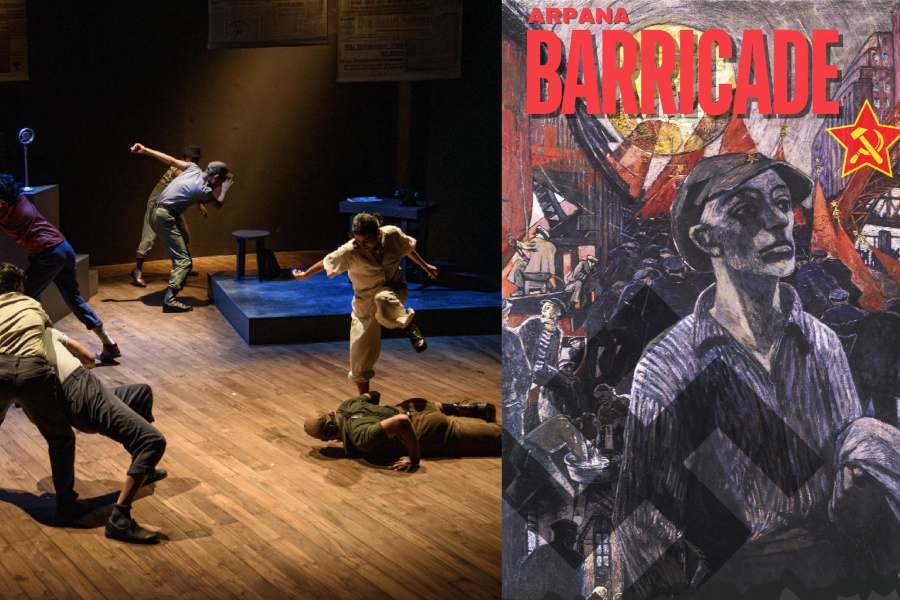

Barricade was re-staged in Mumbai recently. More than 50 years after Dutt first staged it, theatre veteran Sunil Shanbag staged it at the Rangshila Theatre Festival. Translated into Hindustani by Asad Hussain, Shanbag’s production was on a small scale, for 120 viewers, unlike Dutt’s lavish ones that were meant to entertain and communicate ideas to a maximum number of people.

Shanbag’s stage, designed by Shayonti Salvi, had just a few tables and chairs by way of props, and enlarged newspaper pages from Hitler’s time, setting the mood for a story set in 1930s’ Berlin. Even more dramatic was a bright, orange panel with the Nazi swastika. When light designer Hidayat Sami lit it all up and Richard Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries played in the background, the audience was immediately transported to a period of history that can give one goosebumps, even today.

On the stark but evocative stage appears an unshaven, investigative journalist, a popular trope for unravelling stories. His narration provides the political background against which Barricade plays out. Reeling out dates and figures, he points out how, prior to 1933, Hitler’s party failed repeatedly to get an absolute majority at the polling booths.

Thereafter, the scene shifts to the reporter’s office where the

editor is ready with a banner headline for the next morning’s front page. It reads “Communists dance on the road after brutally murdering an 80-year-old popular leader”. The journalist is instructed to file a report to suit the headline, irrespective of what the ground reality is, and without due investigation. Nonetheless, the newshound goes sniffing for leads.

And it is through him that the story unfurls, you get to see how the Nazis set out to tarnish and destroy the Communist-dominated labourers’ party, systematically.

Stirring background music is used by director Shanbag to juxtapose the different

situations. While Hitler’s favourite musician, Wagner, is an appropriate choice for the opening scene, banned swing music plays on a radio in a bar frequented by Communists. “Hitler had very definite views as to what was acceptable music and what was not,” says Shanbag.

He continues, “He was passionate about the anti-Semitic Wagner’s compositions but denounced most contemporary music like swing as degenerate. So swing music became representative of the resistance to the moral policing of the Nazis.

When the Communists react to the desecration of their red flag, the music shifts to Eugene Pottier’s Internationale, a popular anthem of Communist/Socialist movements since the late 19th century all over the world, including India.”

If the Shanbag-curated musical pieces and sound design by Rahul Nadkarni added nuanced depth to the production, making the various strands of Dutt’s

story come alive very convincingly was a team of well-chosen, talented actors.

The frail-looking but steely widow of the slain man, the fearless, sharp-tongued young lady of the Labourers’ Party, the well-read doctor, the tall, aquiline-nosed Nazi officer, the dapper, spineless editor, the unbiased judge, the overconfident, aggressive police official, the protesters, the victims of police brutality… All the dramatis personae were depicted so aptly that the audience got drawn into Nazi Germany in a tiny theatre on a tree-lined lane of Mumbai’s Versova.

Ironically, the sickle and hammer symbols of the flag of the German Communist Party, used on the haunting credits’ booklet of Shanbag’s play to represent

the oppressed labour class, recalled symbols of repression in another play set in the Soviet Union of the 1970s and staged in Mumbai in 2023.

Tom Stoppard’s Every Good Boy Deserves Favour was first staged in the United Kingdom in 1977. Unlike Shanbag’s play, in the Stoppard play the symbols represented a totalitarian state where dissenters were thrown into mental asylums. When one asylum inmate protests that he has no symptoms of mental disorder the doctor tells him, “Your opinions are your symptoms.” Eerily similar is the scene in Barricade wherein the editor reprimands the reporter for his views. “I don’t want truth. I want news,” he warns him.

When news is manipulated, when books are burnt, when the voices of musicians, artists, writers, filmmakers are suppressed, when civil rights and justice are compromised, there is no difference between Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union or any other power-hungry regime.