In Dr Yunus, we trust.” So reads the social media post by Asif Mahmud, who is a student leader and one of the faces of the Bangladesh student protests that had the country roiling all of July and right through a good part of August. Mahmud’s post captures the widespread acceptability of Muhammad Yunus in a country characterised by fractious politics.

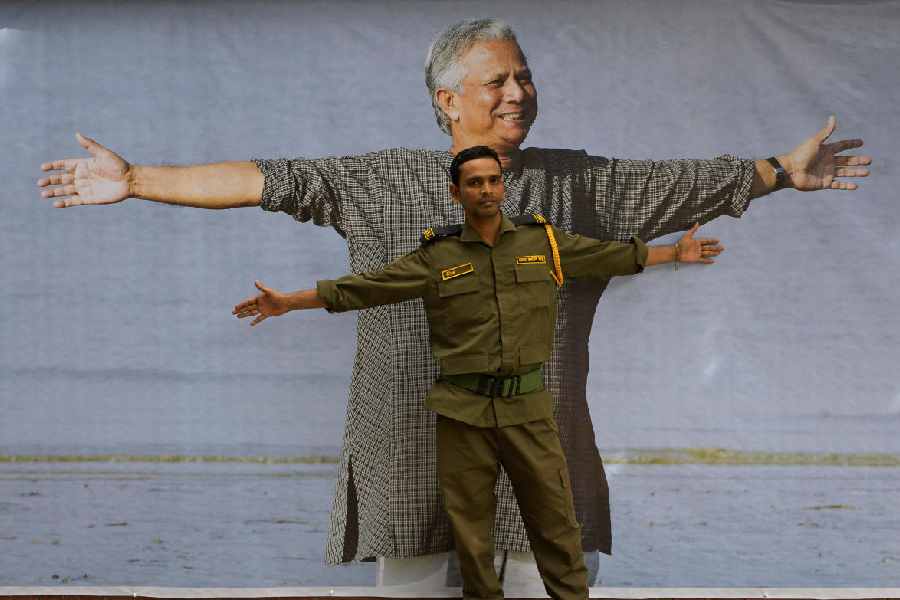

Yunus, whom the world has known for the last 41 years, first as the founder of the Grameen Bank and since 2006 as Nobel Peace Prize winner. Yunus, who has been helming the interim government in Bangladesh ever since Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina fled the country on August 5 following weeks of protests in which at least 300 people died. Yunus who said in his first public statement: “This is our beautiful country with lots of exciting possibilities. We must protect and make it a wonderful country for us and for our future generations.” Hopeful words for a nation that had been through turmoil, but no easy task.

President Mohammed Shahbuddin, who administered the oath to Yunus and his team of advisers, didn’t roll out any terms of reference for the new regime nor did it have any pre-announced agenda.

Initial sound bites from Dhaka suggest that Yunus’s priorities include establishing law and order, reviving the economy and paving the way for free and fair elections.

Amid reports that baby steps are being taken to establish the rule of law in Bangladesh — 1,000 people were killed in less than a month — Shahdeen Malik, a Supreme Court lawyer, outlined the key challenge. “Restoring law and order would be a huge challenge. For years, the police force was being used for political reasons. Because of the corruption in the force, they lost credibility,” he told The Telegraph over phone from Dhaka.

The morale of the force reached a nadir in the aftermath of Hasina’s fall when hundreds of them — the exact count is not available — were killed by those celebrating the new regime. Attempts to rebuild the force began through fresh appointments in key positions. But the overwhelming presence of loyalists of Opposition parties such as the Bangladesh Nationalist Party and Jamaat-e-Islami in the new crop is unlikely to rid the force of political influence, said a source in the force.

The same goes for the legal system. It witnessed sweeping changes after Hasina’s fall. The common accusation levelled at her is that she packed the lower and the upper judiciary with yes-men. No sooner was she gone than the protesters forced senior judges — including Chief Justice Obaidul Hassan — to resign. Forced resignations, be it in the administration or premier academic institutes, are now the order of the day.

Besides rebuilding a battered police force and cleansing legal and other institutions of Hasina loyalists, Yunus and his interim government have a media crisis on their hands. The last few days have seen a sudden spurt in attacks on media outlets. Not just journalists, everyone across the country is afraid to speak freely after the regime change.

A college teacher, who did not want to be identified, said, “It’s not that Hasina was a champion of freedom of expression…. But things have worsened after her fall. People on the streets are randomly checking our phones, scrolling through WhatsApp conversations or social media timelines to figure out political leanings.

I have deleted these apps.”

Malik said he hoped things would be normal in a few weeks, but these developments pose serious questions about the restoration of law and order, which hold the

key to the country’s economic revival.

Bangladesh’s economy, one of the fastest growing in the region for over a decade, is gasping today due to falling foreign exchange reserves, runaway inflation and rising unemployment. No one knows better than Yunus, an economist of repute, that it needs serious intervention.

As of now, the only visible change has been in the highest echelons of the country’s central bank — that is, Bangladesh Bank — and the boards of scores of private sector banks.

Outlining the priority of the government, finance and planning advisor, Salehuddin Ahmed recently said that the interim government’s first objective would be to restore the people’s trust in the banking sector and only then embark on a path to reforms.

The truth remains that drawing up a detailed roadmap for the economy’s revival will take some time, and in that period, the pace of ongoing developments is likely to make things difficult for Yunus.

Post-Hasina Bangladesh has witnessed an all-out attempt to implicate her and people close to the Awami League regime in a multitude of cases, which smacks of politics of vengeance. This bitterness will not help Yunus meet his objective of creating a just and fair society.

“A band of youths, who led the movement against Hasina, has become so powerful… They are dictating the terms, taking ad-hoc decisions and running their writ on institutions. Such actions create uncertainty and slam the brakes on investments,” said a Bangladeshi economist, who did not wish to be named.

Protesters shout slogans as they vandalise a mural of Bangladeshi PM Hasina with paint and mud, demanding her resignation at TSC area of University of Dhaka.

A slew of jailbreaks after Hasina’s fall — each allowing several dreaded terrorists to escape — has added to the security threat in Bangladesh, which witnessed terror attacks from Islamist militants in the past.

The readymade garments sector in Bangladesh, which brings over $42 billion in export revenues and employs over 4 million people, and is the pivot of the economy, may have to pay a heavy price if this uncertainty lingers.

Yunus also faces the humongous task of controlling inflation — it peaked at 11.66 per cent in July.

As Bangladesh is dependent on imports for most essential items, including onions, garlic and even rice, it has to be on good terms with neighbours like India.

Regular reports on attacks on minorities and anti-India rhetoric from a section within the interim government will hamper the bilateral relationship and add to Yunus’s kitty of problems.

The raucous demand to hold elections continues to swell but Yunus needs time to fix all these problems, to usher in structural reforms, and not the very least, to contain the very students’ brigade that foisted on him this great responsibility.