The morning sun slants through the dewy foliage of the sprawling three-acre compound. A light chill clings to the winter air. We are in the hill town of McCluskieganj. We, as in myself and the subject of this piece, McCluskieganj resident Deepak Rana.

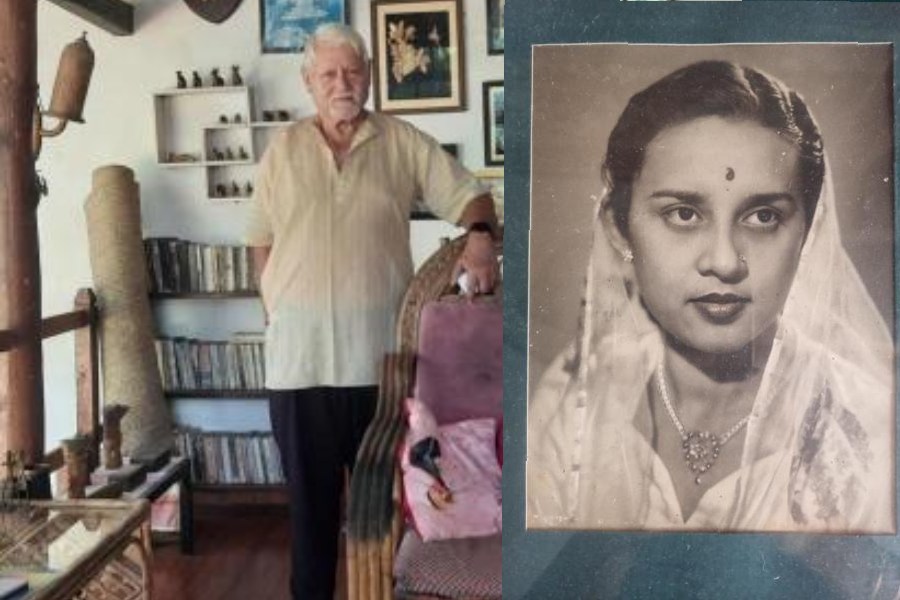

Rana, 82, moves with the ease of a man acutely familiar with his surroundings, pausing now and then to brush his fingers against leaves or to pull out weeds. His voice, rich and contemplative, breaks the morning silence as he begins recounting the tale of his family’s arrival in this quiet corner of Jharkhand.

“It was 1962,” he says. “My father, Colonel Bilayat Jung Bahadur, was stationed at Namkum cantonment near Ranchi. A simple picnic brought us to this place...”

Deepak Rana is the descendant of Jung Bahadur Rana, a prominent military figure of 19th century Nepal. In 1885, the Prime Minister of Nepal Maharaja Ranoddip Singh was murdered by his nephew in a palace coup. Soon after, Rana Padam Jung, the surviving son of Jung Bahadur Rana, fled the country and settled down in Phaphamau near Allahabad.

Padam Jung’s son was Col Rana Judha Jung Bahadur, whose son was Col Rana Bilayat Jung Bahadur, a World War II and 1962 Sino-Indian war veteran. Col Judha Jung was a decorated soldier. He became army chief of the princely state of Tripura and lived there for a while.

The decision to make McCluskieganj home was his wife and Deepak Rana’s mother Kanchan Prabha Devi’s. She was ailing and the town’s climate and waters seemed to rejuvenate her. As Rana tells the story, those days, there was no road, no infrastructure in McCluskieganj. He says, “We built a house, laid down roots and McCluskieganj started becoming a part of who we are.”

“Fifty years ago, life was simpler,” says the old man, bending over a bit to adjust a wayward bunch of marigolds. He talks about the Anglo-Indian settlement there, a place fondly known as “Gunj”; a lot of retired army officers also settled there.

Rana continues, “The Anglo-Indian community lived in a bubble — proud and detached. It was 1972 or 1973 when the last Anglo-Indian family left McCluskieganj. Then came the Bengalis.”

The arrival of Bengali families began to reshape the character of the town. “They brought literature, they brought music, they brought Durga Puja, Kali Puja and above all, a new vibrancy,” says Rana.

There was a time when this — Palamau and its adjacent belt — was the favourite “circuit” of travel-thirsty Bengalis; they commonly referred to it as “paschim”. Sanjibchandra Chattopadhyay wrote about it in his book Palamau. Sunil Gangopadhyay and Buddhadeb Guha also wrote about these places.

But this phase too passed. The rise of Maoist insurgency cast a shadow over McCluskieganj. The Bengalis fled the place.

Rana says that by this time his family had earned a reputation for being McCluskieganj loyalists. Their commitment to the poor earned them respect. He says, “I told them, disturb me if you must, but leave the schools and railways alone. And they listened.”

With the help of the local government as well the Ramakrishna Mission, Rana has set up in McCluskieganj 27 primary schools and two middle schools for tribal children. “Education is liberation,” he says. Rana himself went to school in Shillong, St Edmund’s School, and thereafter St Xavier’s College in Calcutta.

The stroll leads us past a secluded corner of the garden, where a jasmine vine droops over a bench. Rana sits down, pauses for a moment and starts to talk about time past.

As the sunlight grows stronger, Rana watches birds dart through the crisp air. The chat takes a serious turn as he speaks of the wave of “commercialisation” that denuded the heritage of McCluskieganj. “What truly broke my heart was when settlers from other parts of the country arrived, not to be part of the community, but to exploit it,” he says. “They tore down old houses… so many Victorian houses. They simply destroyed

the delicate harmony that once existed here. The soul of McCluskieganj was their target.”

A few moments pass by quietly. Rana’s face brightens again as he talks about his daily routine. “Reading, gardening, playing with my grandchildren,” he says with contentment. “Lately, I’ve been reading Nexus — a book on AI. It worries me. Technology, if used unwisely, could eclipse the very humanity that binds us.”

The morning sun climbs higher. Rana says, “I have never craved money. Maybe it’s because I have always had enough.” The family once held chunks of shares in the tea gardens of the Northeast and owned various jute mills.

Instead, Rana stands as the personification of humility, generosity and the unyielding spirit of McCluskieganj.

He says, “I am McCluskieganj…”