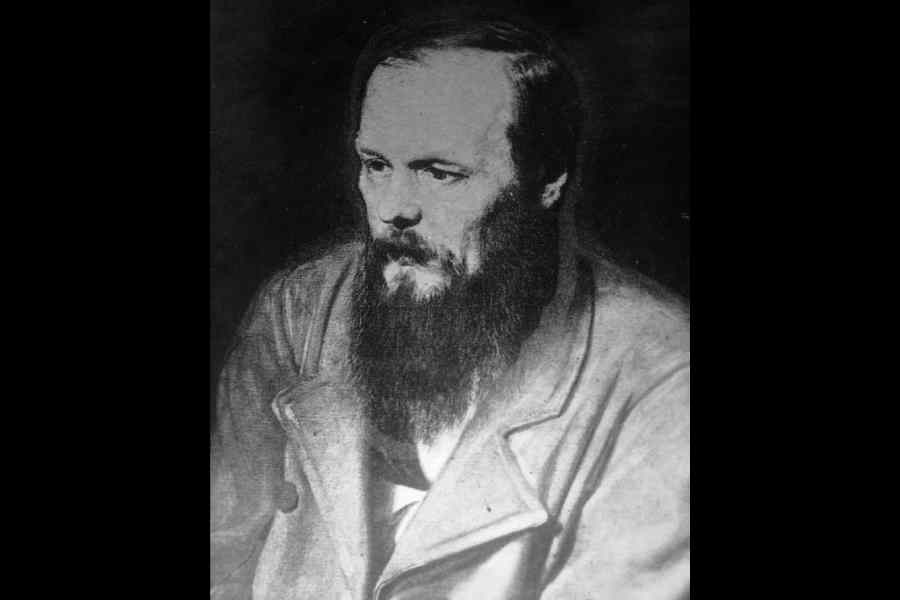

FYODOR'S FALLACY: “I have been five days in Wiesbaden and already I have lost everything, the whole lot, even my watch,” Fyodor Dostoyevsky wrote in the fall of 1863 to a fellow Russian novelist, Ivan Turgenev. It had been only a few months since Dostoyevsky had played his first round of roulette at the casino in Wiesbaden, Germany, and already he had cycled several times through a sequence known to gamblers everywhere: Win big, and then lose bigger.

In the years that followed, Dostoyevsky travelled frequently between the flourishing German spa towns of Baden-Baden, Bad Homburg and Wiesbaden, trying his luck again and again in their opulent casinos, a stomping ground for Europe’s aristocracy. By 1866, he had entered into a perilous wager with his publisher to avoid debtor’s prison: Deliver a new novel by Nov. 1 or lose the publishing rights to his entire catalogue.

The result was The Gambler, dictated in three weeks to the stenographer who would become Dostoyevsky’s second wife, Anna Grigoryevna. The novel follows Alexei Ivanovich, a young Russian tutor who travels with an imperious general to the fictitious German town of Roulettenburg and spirals into compulsive gambling.

His only book set primarily in Germany, The Gambler is in many ways a repository for the acerbic disparagements of a writer who had a love-hate relationship with the country. “I sit brooding in this melancholy little town,” says Alexei, the book’s narrator, “and how melancholy the little towns of Germany can be!”

Though modelled most closely on Wiesbaden, Roulettenburg is most likely a composite of the three spa towns where Dostoyevsky gambled — and lost. Baden-Baden is still a tourist destination, but none of them are the hot spots they once were. Although they long remained popular with Russians, that all changed when Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 led to increased travel restrictions.

An admirer of Dostoyevsky’s work, I first read his books as a teenager, and then again while living in Moscow a decade ago. As a longtime expat living in Berlin — someone who has occasionally felt out of place in Germany — I am particularly drawn to The Gambler, which is told through the eyes of another out-of-place foreigner.

I also wanted to see what remained of the once grand spa towns he described at a time when the aristocracy travelled across Europe to “take the waters”, to see and be seen.

And so last autumn, I caught a train south in search of Dostoyevsky’s Roulettenburg.

Nobility hot spot

On the right bank of the Rhine, Wiesbaden reached its heyday in the late 19th century after its annexation by Prussia led to its rise as an international spa town, popular especially with the Russian nobility. When Dostoyevsky went there, initially to seek treatment for his epilepsy, it was home to more millionaires than in any other German city.

Today’s Wiesbaden is not the cosmopolitan playground it once was, but the remnants of its glory days are everywhere — in the fountains and colonnades that line its grand boulevards, in the Art Nouveau villas and in Gothic Revival churches that fill the downtown area, which was barely damaged in the world wars.

I booked a room at the Hotel Nassauer Hof, a 200-year-old grand hotel atop a thermal spring that hosted Dostoyevsky in 1865, when, the hotel says, he “loses 3,000 roubles at the casino in short order and leaves hastily without paying his bill”. Today, the Nassauer Hof feels largely stripped of its history despite the framed images of past prominent guests, including Czar Nicholas II and Karl Lagerfeld, that fill the lobby.

But if you try hard enough, you can imagine the hotel where much of The Gambler takes place, where Alexei returns one day to find Grandmother, the Russian matriarch whose fortune the general expects to inherit soon, “enthroned at the top of the wide flight of steps to the hotel door, in the chair in which she had been carried up them”.

Kurhaus Baden-Baden, where Dostoyevsky used to sit in a corner of the Florentine room and where he lost all of his and his pregnant 21-year-old wife’s travel money, as well as the money he made by pawning their belongings, down to Grigoryevna’s wedding band Sourced by The Telegraph

The Kurhaus, a neo-Classical spa structure built in 1907 that replaced the one from Dostoyevsky’s time, is across from the hotel. These days, it serves as a convention centre and concert hall, and while there are no longer any baths, a casino is still in operation.

I walked across the vast, grass-covered square flanking the Kurhaus, where a group of women doing yoga ruptured the 19th-century atmosphere. The casino inside bears little resemblance to the one where Dostoyevsky gambled, aside from an original roulette wheel enclosed under glass. But it wasn’t hard to draw a connection between the affluent players lazily staking bets and the gambling gentlemen Dostoyevsky depicts, who bet “only for amusement, only to watch the process of winning or losing”.

After losing a small amount of money myself, I went looking for the most Wiesbaden of dinners, which I found up in the hills at Apfelweinstube im Himmelreich, or Apple Wine Tavern in the Heavens. Overlooking rolling wine country, the tavern serves traditional specialties. I tried the homemade cider, which was good, and the “hand cheese with music”, a translucent curdled sour milk cheese topped with raw white onion, vinaigrette and caraway seeds, which was not quite as upsetting as it sounds.

The next day, I went to the fountain in the city centre that sits atop a sodium chloride hot spring, continuously pumping sulphurous, mineral-rich water naturally heated to about 66° Celsius. I downed a steaming cupful of the stuff, a bit like guzzling hot sweat.

Later, after coffee and strudel at Café Maldaner, a dainty Viennese-style café that Dostoyevsky is said to have patronised, I caught a train 40 minutes northeast to Bad Homburg, which sits at the foot of the Taunus Mountains, just north of Frankfurt.

Bad Homburg

Another once famous spa town loved by Russian nobility, Bad Homburg is one of the wealthiest towns in Germany, advertising itself with the slogan “Champagne air and inspiration”.

Home to the country’s oldest golf course and Europe’s first tennis club, its 116-acre spa park is a lush terrain of 19th-century gardens, neo-Classical monuments and fountains spraying naturally carbonated mineral water from one of the 14 geothermal springs beneath the town.

Designed by Peter Joseph Lenné, the Prussian landscape architect behind Tiergarten in Berlin, it is the only oneof Lenné’s designs that has been preserved in its original form.

I walked through the park’s mist-covered gardens past the Kaiser-Wilhelms-Bad, a neo-Renaissance spa built by the last German emperor. Today it houses a day spa, where visitors — using day passes that cost 69 euros each — can immerse in saltwater pools, be massaged with mineral-rich clay or take hay steam baths with dried grasses, herbs and meadow flowers.

I stopped in at a cheaper spa at the other edge of the park, Taunus Therme, to find it full of naked Germans loudly cavorting in pools shaped like pagodas or lying out in the “Hamam paradise” within the 1001 Nights Sunbathing Garden.

Like Dostoyevsky, I decided to skip the baths and headed for the casino.

“If you gamble in small doses every day, it is impossible not to win,” Dostoyevsky wrote to Grigoryevna, his second wife, in 1867. By then, the newlyweds had moved to Europe to escape his creditors, but Dostoyevsky kept returning to — and losing at — the roulette tables.

Opened in 1842 by François and Louis Blanc, twin brothers from Paris, the original casino contained ballrooms, a restaurant, castle-like side wings, a theatre and the first single-zero roulette wheel, increasing players’ odds against the house. But when a ban on gambling was imposed in 1872 throughout the newly formed German empire, Bad Homburg fell into decline and was destroyed by Allied bombing, reopening in 1949 under the motto “the mother of Monte Carlo”.

The current casino, the low-ceilinged, 1950s-era Spielbank Bad Homburg, has none of the grandeur of the earlier one. And, unlike at Wiesbaden, there is little to no people-watching. I finished my complimentary drink at the Dostoyevsky Bar and headed toward the train station, passing a monument of the Russian author sitting on a park bench, clasping his hands in despair.

Baden-Baden

I took a train south to Baden-Baden, at the edge of the Black Forest near the French border. Baden-Baden is nothing if not scenic, with its rain-washed cobblestone alleyways lined with belle epoque mansions and flowering horse chestnut trees.

On Sophienstrasse, the leafy main street, I checked into Hotel Quellenhof, a budget hotel that claims to have hosted Dostoyevsky.

The town seemed quiet as I walked along the Oos river, which flows through its centre.

I crossed the Oos to the 19th-century Kurhaus Baden-Baden, fringed by forest, with Corinthian columns, a paired-griffin frieze and, inside, what the German actress and singer Marlene Dietrich called “the most beautiful casino in the world”.

The casino still looks much as it did in its heyday, with voluminous crystal chandeliers, red silk walls, gold leaf and Italian chinoiserie. Dostoyevsky used to sit in a corner of the Florentine room, a guide told me. It was there that he lost all of his and his pregnant 21-year-old wife’s travel money, as well as the money he made by pawning their belongings, down to Grigoryevna’s wedding band.

There are no longer baths at the Kurhaus, so I took the waters at Friedrichsbad, a tiled Roman-style bathhouse that opened in 1877 where you move through 17 stations of thermal water pools and steam rooms (day pass, €35). Steps away is the house where the Dostoyevskys lived during that fateful summer in 1867, a period memorialised in the first of Anna Grigoryevna’s two memoirs, published after her death.

“I suffered beyond words waiting for Feodor,” she wrote. “I cried and cursed myself, roulette, the Baden-Baden casino and everything on Earth.…”

Their original home — two small rooms above a blacksmith’s shop at Bäderstrasse 2 — has been demolished, but a bust of the writer and a sculpture of an open book are affixed to the façade of the house built in its place.

After Baden-Baden, the Dostoyevskys remained in Europe for another four years, living between Switzerland and Italy, a difficult period during which his health deteriorated and their first child died at 3 months old. In 1871, Dostoyevsky returned to Wiesbaden and fell again into a ruinous bout of gambling.

“For 10 years,” he wrote to Anna Grigoryevna from Wiesbaden, “I dreamed about winning money … But now it is all over!” And this time, he meant it. By most accounts, he never gambled again, nor did he return to Germany. He and his wife settled in Russia and had three more children.

But difficult as it was, Dostoyevsky’s decade in Germany was productive: He wrote Crime and Punishment, The Idiot and Demons — and, in one of literature’s great love-hate relationships, Germans would populate his novels for the rest of his life.

New York Times News Service