Evolution has allowed humans fine brains and bodies, but when it comes to grace and discipline, there remains much to be desired. I say so with good reason because some of us have front-row seats in one of the most happening theatres. A building complex within the walls of which deplorable deeds are dealt with. Murder, rape, conspiracy, fraud, negligence and whatnot. Only humans are capable of committing such misery, on to their own kind as well as others.

That theatre is the Alipore district and sessions court.

I am a tree. A wild almond, in their dictionary. In 1753, a wise old man called Carl Linnaeus named me Sterculia foetida. In Latin, “stercus” means dung and “foetidus” means foul-smelling. I was awarded this distinction because my flowers give off a smell of rotting meat and bad breath, I am told. I have other names too — Java olive, skunk tree, poon tree, etc. Too much detail... But there’s one moniker that might delight — baksho badam. Literally, nuts in a case. Now don’t prod a figurative meaning, because I would throw it right back at you. The fruits of my bearing are enclosed in a hard, rounded case. Pretty peculiar actually, edible too.

I have been here for years now, just 30 metres away from the main building. A two-foot high platform circles my base. Hawkers spread their ware on it — fruits, pens, envelopes, combs, small toys. The cement cracks from time to time, for my roots are alive and strong. The humans mend it, and all goes on as usual. Thus I’ve been watching the goings-on for over 100 years. Or maybe 150, who knows? I am old and I forget my year of birth.

Ask Samiran Chakrabarty, who has been a clerk here for over 50 years, and he’ll say, “These massive trees were planted by the British.” The court building was built in 1857. That makes it 167 years old. “I joined in 1976 and even then it was this tall and strong,” he says of me. Now do the maths.

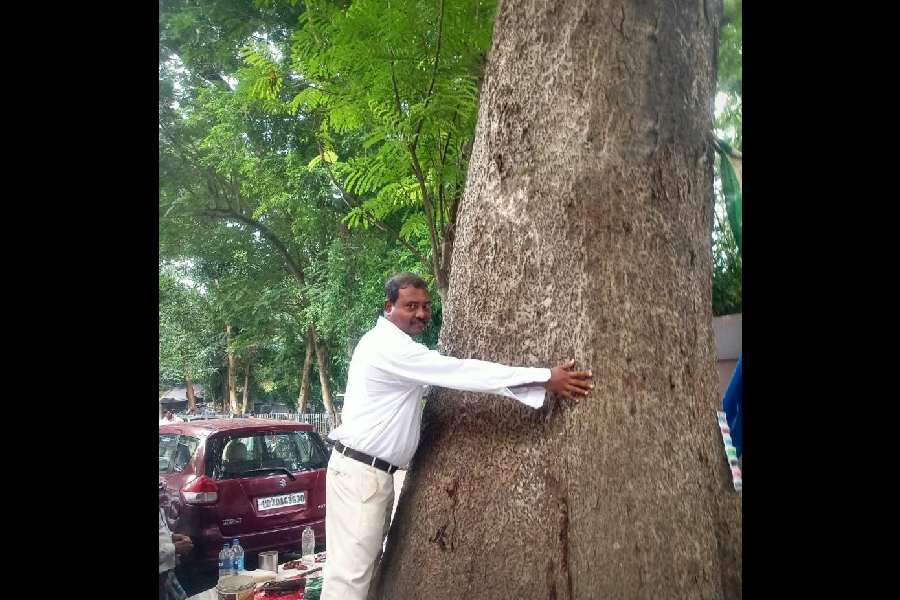

You could say I’m a large tree with a straight, sturdy trunk. My height is 80-90 feet. Some of my ilk shoot up to 150 feet. Some tried to measure my girth — it took three them to embrace me. My branches spread like whorls, and the leaves open up like stars.

Alipore district and sessions court. Paromita Kar

There are about 15 of us here, of such vintage. Then there are birds and cats, squirrels and insects. It’s the jungle of life, with our own rules. If a branch is infested, I must shed it so that the rest can live. That’s the order of things, as opposed to the breaking of it. There are no records of our population, though. We ofxylem and phloem, girth and crown, auxinsand gibberellins...

Talking about records, about 50 metres away from where I am is the records department. It has files and boxes of paperwork, necessary proofs of the processes that go on within the walls of the offices. There was a logic to its location. At the time of planning, there used to be a pond in front of that storehouse. So if a fire broke out, water would be easily available. Today, however, what remains in place of water are heaps of rubbish overgrown with weeds. Over the last few decades, tall buildings have sprung up in the neighbourhood, with deep roots of concrete and metal. That sort of tampering disturbs the flow of life, under the ground as well.

But of course, there are humans and there are humans. One who goes by the name Mantu Hait does keep a record of sorts, in his head. He has been familiar with my kind since he was a child, when he would play football and cricket on the grounds nearby. He’d venture amongst my kind, feeding his curiosity. One fine day in 2005, he started coming wearing a black coat over white shirt and trousers. If you’ve heard of the urban forest in Chetla, well he’s the one behind it.

I’m digressing. What I wanted to say is that this civil lawyer also ensures my sap lives on. In December, when I let go of my mature seeds, Hait collects them. “I have planted the saplings in many places across Bengal, wherever we have plantation projects,” Hait says to whoever cares to listen. Often on Sundays, he comes in when no one else does.

Do you know what is most dear to me? Old times. Moments I hold in the core of my being, literally. From the early part of the last century, when young men and women revolted against the imperial rulers and were tried for treason right here. I preserve their sweat and breath, their words and agonies.

It was 1908. Emperor v Aurobindo Ghosh and others, also called the Alipore Bomb Case, was “the first state trial of any magnitude in India” and the first in a long line of revolutionary conspiracy cases.

There’s a whole building dedicated to the momentous trial. Much of it is preserved — the cage-like enclosure for the revolutionaries, the benches, the dock for Crown witnesses, judgements, confiscated letters, shells, books carved to hide revolvers... In my heartwood I hold a bit of that turbulent air.

Air. Well, I haven’t even gotten to that part. Only a few days ago, a man sitting in my shade was thinking aloud, admiring the mango and mahogany trees that abound here. “This tree has no value,” he said of me.

The truth is everywhere but often unseen. Some learned people have calculated that on an average, a 100-year-old tree produces about 6,600 kilograms of oxygen during its lifetime.

I rest my case.