The 1920s were a tumultuous time in India’s struggle for Independence. Young men and women associated with the liberation movement were often posted in places far away from their native lands, and involved in patriotic activities that never guaranteed them safety. One of these heroes whose story has now been forgotten is Nandlal Kapur, who, like many others, was initially recruited as a spy by the British. However, as he navigated the undercurrents of rebellion in the country and met revolutionaries determined to break free from colonial rule, Nandlal stood torn between loyalty to his role and his love for his country. Eventually, he became a double agent and chose to contribute to India’s emancipation.

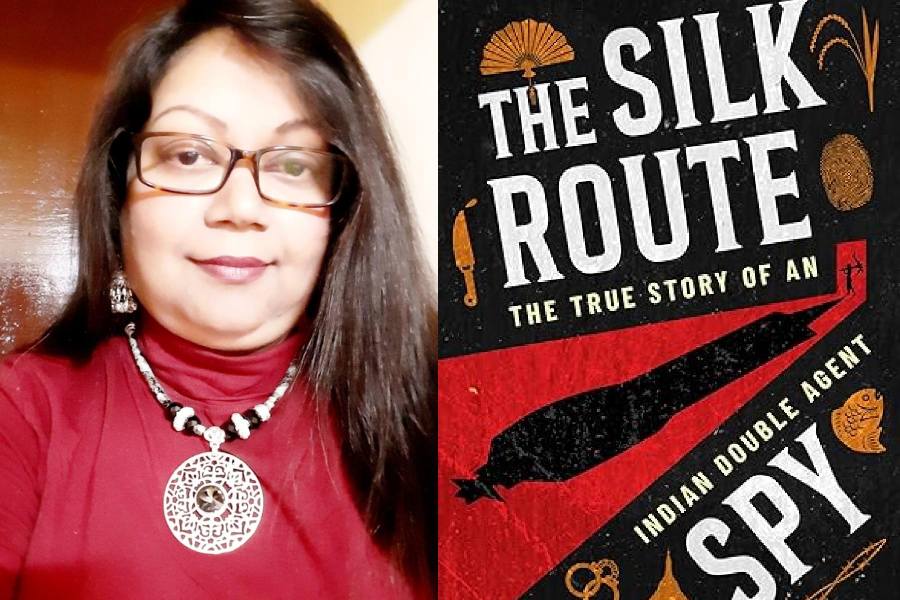

Kapur’s story has now been documented and re-imagined by his granddaughter-in-law Enakshi Sengupta, whose latest book The Silk Route Spy is an account of an extraordinary life whose intricacies are now lost to time. Charting Kapur’s journey across India and abroad during the struggle for Independence, the book is a fictionalised version of history, taking readers on a ride that shows them the sacrifices made by those who freed the country. A The Telegraph chat with Sengupta:

You mention in the book, both in the introduction and as your final words, that you heard the tale of Nandlal from your husband, but I’m sure a lot of background checks must also have gone into the writing process. What kind of research did you undertake to ensure historical accuracy, while simultaneously building at least some parts of the book from your imagination?

Yes, you are right. What I heard was more of storytelling, that too from a personal point of view. What it lacked was historical underpinnings. For example, I knew Nandlal Kapur travelled to Burma or, in fact, to Shanghai. I also knew that he took the ship and a flight to Shanghai. That’s all that I was told. I had to look for the mode of transportation from Calcutta to Rangoon, the name of the shipping company, the route, and so on. I had to corroborate the historical incidents like what was happening in Nanjing, the geo-political situation in the Malay peninsula, and even the products that were being traded from Hyogo port in Kobe, at that time.

I depended a lot on open sources like archived film clippings, journals, news clips, and articles from the Central University of Punjab, Bhatinda. There were lots to read before I could connect the dots and ensure that everything that I cited matched with history on one hand and the narrative that I heard on the other.

Did you plan on writing the book as a biography of sorts or are there any specific themes you wanted to highlight?

When I embarked on writing the book, I had nothing planned. I just wrote and the book started shaping on its own. Sometimes I feel as if I was writing in some kind of trance!

I wrote what I heard, what I felt, and what remained unsaid. I wanted to highlight the contribution of a man who has been long forgotten. He remained anonymous and faded into obscurity. No one knew the perils that he fought, the battles he waged with himself and with his surroundings. A man torn away from what was familiar and comfortable and trying to carve out a niche in alien soil, yet remaining true to the cause he believed in.

Was there a particular scene or chapter in The Silk Route Spy that was especially difficult or emotional for you to write?

I would say the epilogue and the prologue. It brought back memories of my late husband, his animated gestures, the excitement in his voice, and the twinkle in his eyes when he used to narrate the story of his hero, his grandfather. I could visualise him talking to me, sitting perched on the edge of the bed with excitement. It brought back memories of how he related his stay in Malaysia, visiting Johor Bahru and he would speak non-stop about what his grandfather had seen or done.

Many historical novels teach readers about the past. Was your goal more to entertain, inform, or create a blend of both?

I would say it was to inform. To inform readers about the contribution of Nandlal Kapur, to inform how a silent battle was being fought for Independence outside India, in faraway shores. How people like Jivat Singh, Anandilal, or Hashmukh remained true to their country. Their contributions were not some amplified versions of arsenal and killings but what they did was no less significant.

What do you hope readers take away from the novel, both in terms of history and the story itself?

I wanted to transport the readers to a world that has been long forgotten. I hope they get a glimpse of the life of a spy and a double agent who operated in difficult circumstances. I would be happy if they remembered all the unsung heroes who helped us become the glorious nation that we are today. There were battered Indian soldiers in the Malay peninsula, mainly from the Punjab regiment who were wounded and hungry and left behind by the British Raj after they fought a battle that was not their own. They didn’t forget their country, they regrouped, gathered their strength, and formed the INA. These people deserve to be remembered.

Pictures: The author