The first recorded instance of a proposal for a zoo in Calcutta was raised in 1842. There was an attempt at it in 1866 and the Maharaja of Burdwan was among those who even donated money for the cause. But it turned out to be an abortive attempt. Nothing worked out till 1875, as recorded by John Anderson in Guide to the Calcutta Zoological Gardens. It was a joint effort of the government of Bengal and the public, notes Anderson. The institution was established towards the end of 1875.

Babu, Mastan and Chhotu

Babu is the eldest of them, close to 36 human years, with a gentle, reserved air about him. The others are young and full of energy. Pointing to a swing stand inside their enclosure, the Alipore Zoo educator says, “I think Mastan or Buri tore down the swings, or maybe it was a group effort, I am not sure.” The chimps climb onto the iron jungle gym, take dips in the pool and if the sun is too bright, they rest in the night shed at the back of the enclosure. There are logs scattered around just so that the chimps can scratch their backs on them and relax. They love public attention and were rather morose during Covid-19 when visitors stopped coming. One of the walls of the enclosure has been painted with a vibrant forest scene with chimpanzees playing in it. Says the zoo educator, “The painting was supposed to make them a little less lonely.”

Titi and Rani

Trunk raised in the air, Rani ambles towards the edge of the enclosure, two or three white birds in tow. Suddenly Titi starts racing Rani, her hurried footsteps thumping away. She too raises her trunk. The birds, now bored with the sisters’ shenanigans, turn around and fly away. Rani and Titi are the two elephants of Alipore Zoo. They are 10-12 years old. The zoo dietician says, “Rani and Titi share among themselves, every day, one kilogram of rice and half a kilogram of sprouts dipped in jaggery. Then they are served 140 kilos of sugarcane top leaves.” For lunch, the girls are served two and a half kilograms of rice and musur dal, soaked and wrapped in banana leaves. And around early evening, 10 kilograms of bananas. Other than that, they are given coconut, pumpkin and a few other fruits on a weekly basis. The elephants are very particular about hygiene. They pick their food in their trunks, and also clean the food by dipping it in water before eating. They like to clean themselves sometimes, by rolling on their backs in the dust.

Mangal and Sons

You wouldn’t imagine it, but it seems these long-necked beauties are prone to throwing tantrums. One moment they stand still as the zookeeper tends to them and the very next, they take off in a random direction. The zookeeper says, “If you are not careful while handling them, you may get kicked inthe chest, which is quite deadly.” Mangal is the eldest of the lot, about 16 feet tall and has the darkest patches, given his age. Neck bent over the night shed, he seems to be deep in conversation with another giraffe while the younger ones, his family and friends, frolic in the open field in front. Some of them munch on the leaves of trees growing in their enclosure. When a lot of visitors gather, they run to greet them. Giraffes have a unique friendship with their keepers. The keepers feed them, apply medicines to their wounds and bring themback to their night shed for sleep. Food is not always served to them the usual way. “Their neck movement is very important, so we hang some of their food from high rails,” says thezoo educator.

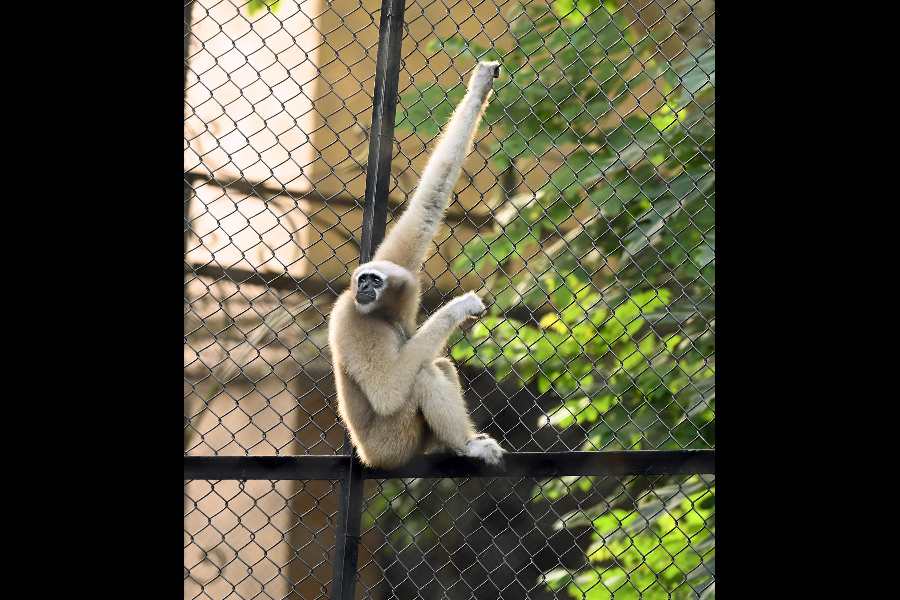

Hoolock Gibbons

They are native to the northeastern states. The zoo houses two female hoolock gibbons, elusive creatures and not too fond of human interaction. Even their keepers have to tend to them from outside their enclosures. These primates are frugivores and folivorous, meaning they feed primarily on fruits, flowers, seeds, tubers and leaves. But at the Alipore Zoo, they are served boiled eggs too. Hoolock gibbons are rather dramatic. Picture this: a quiet day at the zoo,visitors strolling by. Suddenly a sharp sound rings through the air, followed by another. It continues for half an hour at a stretch. Not a bunch of interlopers disrupting zoo peace, just two hoolock gibbons having a chat. “That’s just how they talk,” says the zookeeper.

Katha and Koli

The Alipore Zoo once housed what is believed to be one of the world’s oldest living creatures, a 250-year-old Aldabra giant tortoise named Adwaita. “After he (Adwaita) passed away in 2006, his native country Seychelles gifted us another pair of tortoises,” says Subhankar Sengupta, who is the director of Alipore Zoo. He adds, “Our chief minister Mamata Banerjee named them Katha and Koli.” Katha, the male tortoise, is about 50 years old and Koli is about 40. At first glance, the pair looks like two large boulders, but the longer you look at them, the more interesting they get. Pointing to a tamarind tree overarching their enclosure, the zoo educator says, “Sometimes, tamarind drops from the tree and we have noticed that Katha and Koli love snacking on them.” The duo is most active during the monsoons when they get into puddles of water and take frequent mud baths. However, when the weather is too hot or cold, they simply cosy up inside their shells and take a nap.

Raja and Co.

The Alipore Zoo has about nine tigers, among which four are white. The most popular of them is called Raja. Too much human interaction stresses them out. Says the zoo educator, “We release one tiger every day into the enclosure and keep the others in their sheds to give them a break from visitors.” As if on cue, a Royal Bengal Tiger, possibly Raja, comes out of his den yawning. Visitors are gathered in numbers, just to catch a glimpse. Raja walks around a little, and another big yawn exposes his fangs. Disinterested, he then goes back to his den to sleep the morning off. When it comes to the tigers, making a mistake is simply not an option for zookeepers. Food is served to them by lifting the gate a few inches with a remote control. “You lift it too high and you are dead,” says the keeper with a knowing smile. But if you look closely, you will find squirrels strolling around their enclosure, going about their day nonchalantly. Perhaps, they have an agreement. According to the zoo educator, the tigers won’t harm anyone unless they are hungry. But then again, it is a claim better left untested.