A state that is hungry, it can be argued, is perpetually angry. Jharkhand, where a Muslim man was lynched on Wednesday on the suspicion that he was a thief and where a Dalit woman allegedly starved to death on Tuesday, seems to be both as it prepares to vote in a government again.

Scratch the shiny veneer of the “ease of business” surveys that place Jharkhand among the top-performing states, and less flattering surveys emerge.

The multidimensional poverty estimates made by the UNDP and Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (2015-16) point out that 46.5 per cent of Jharkhand’s population is poor.

The National Family Health Survey IV (NFHS-IV) of 2015-16 says 48 per cent of Jharkhand’s population is in the lowest wealth quintile (the poorest one-fifth of the population). Its parent state, Bihar, has 53 per cent of its people in the category.

Savitri Devi of Chirudih, Giridih, died on Tuesday. Her marginal farmer husband Ramesh Turi said she had not eaten for two days and they did not have a ration card despite applying for one last year.

In Bokaro, Mubarak Ansari was killed by a mob after he and another man were caught “stealing” a vehicle battery from a bike service centre on Wednesday.

Asked to react on Savitri’s death, which the government has denied to be due to hunger, Right to Food activist Siraj Dutta pointed out that one-third or 33.33 per cent of Jharkhand’s adult women had less BMI (body mass index) than ideal.

That means they are too thin for their age. The national figure is 10 notches lower, at 23 per cent.

“It gets worse,” Dutta added. “Almost half of Jharkhand’s children are stunted, compared to 38 per cent in the country,” he said. Jharkhand, he said, had the highest proportion in India of children under 5 years whose malnutrition is visible in all three forms — stunting, wasting, and low weight. “As many as 10.9 per cent of the state’s children belong to this category.”

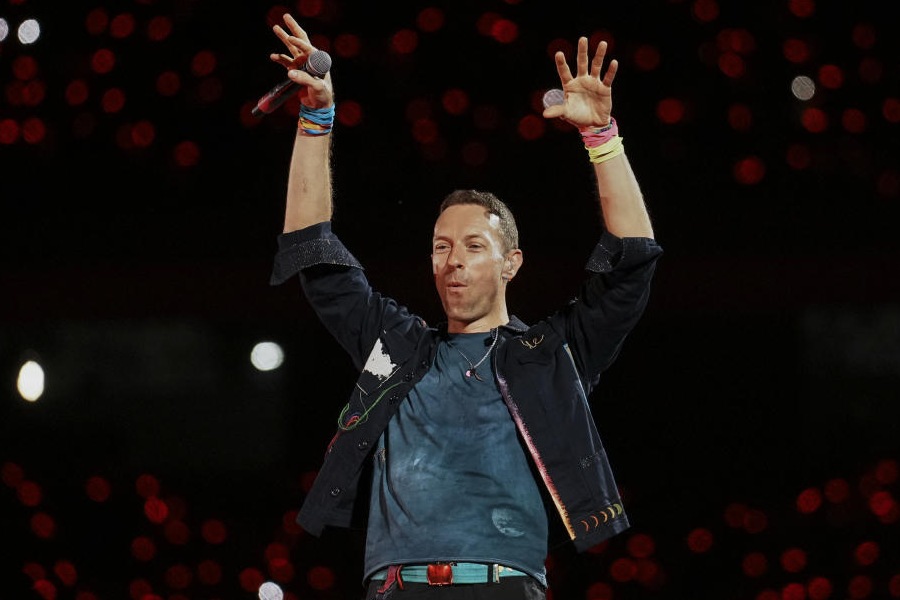

Tabrez Ansari File pictures

The Raghubar Das government did claim a huge leap in transparency after compulsory Aadhaar linkage to ration cards, Dutta said, but it “keeps revising” the exact figures about the cancelled fake ration cards.

“The ground reality is that many genuine card holders are deprived of food grain from the public distribution system owing to Aadhaar snags such as a mismatch in biometric identification. Poor tribals and Dalits are the worst hit.”

Does hunger — or poverty — enrage people more?

Jharkhand has seen at least 23 alleged hunger deaths and 22 incidents of lynching in the last five years, including those of Savitri and Mubarak. Mob anger has acquired a political colour, with cow protection groups active across the state. Reprisal for alleged thieves — Tabrez Ansari in Seraikela in June this year, Mubarak Ansari in Bokaro on Wednesday — is also harsh. Nishant Goyal, an associate professor with the Central Institute of Psychiatry in Kanke, Ranchi, explained that anger was related to stress.

“An individual is now under tremendous stress due to financial and social factors with no avenue to share it with anyone,” he said.

He said a vulnerable man who feels trapped in a helpless situation might feel stronger in a mob and lash out against other vulnerable individuals.

“Also, acceptance of others’ views has reduced. People are less accommodating. The situation is aggravated by other factors, such as media reports, social media rumours, polarisation in society,” he added. “Such polarised and angry people can go to any direction and do anything, even lynch someone in the illusion of safety in a mob.”

Meanwhile, the cases pile up. On October 19 this year, Hazaribagh police rescued Vikas Yadav, 35, who a mob had tied up and thrashed on suspicion of being a thief. He was looking for an isolated place to attend nature’s call.

On September 11, again in Hazaribagh, a senior executive of Larsen & Toubro, Md Shahid Siddiqui, was attacked by a mob that thought he was a child kidnapper.

He was inspecting construction work of a drinking water project.