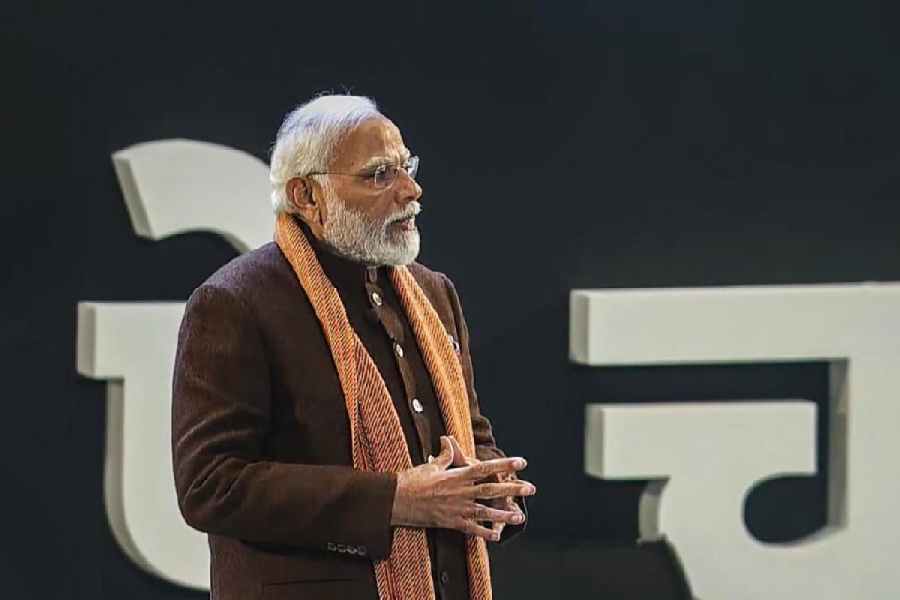

A handful of partymen are crunching numbers in the Congress war room in the Jharkhand capital. Some of them have one eye on the television that is screening Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s roadshow, his first in Ranchi, that is being lapped up by a frenzied crowd running into lakhs. Obviously, they are not enjoying the spectacle. “BJP ne kabhi socha bhi nahi tha ki Modi ko yeh sab karna parega Ranchi mein vote ke liye (BJP never thought that Modi would have to do this in Ranchi for votes),” said one of them, trying to suggest that a united, and therefore, rejuvenated Opposition was the reason behind the ruling party’s high-decibel campaign in a state where it won 12 of 14 Lok Sabha seats in 2014.

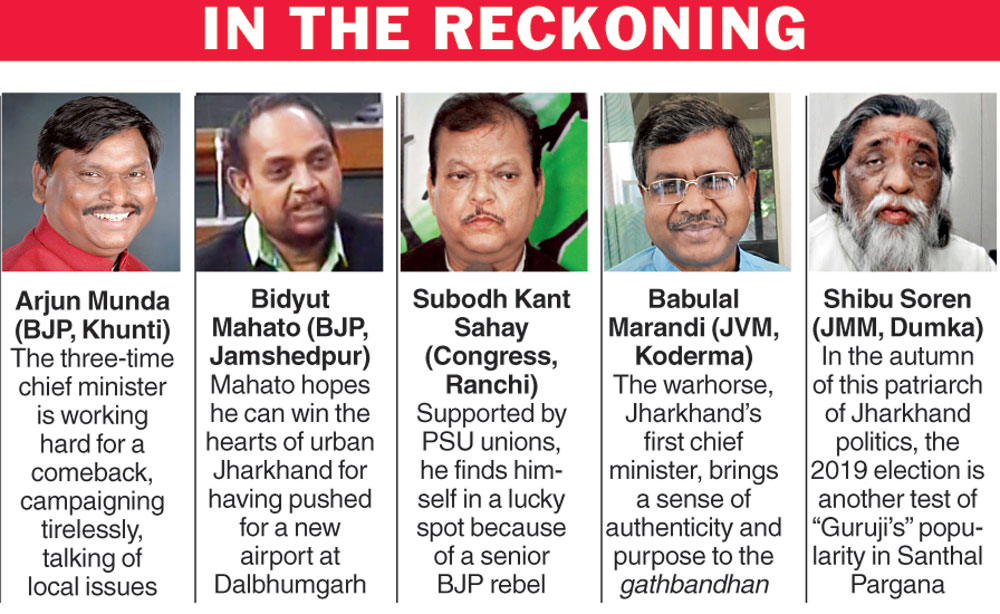

Having propped up lame duck Independent Madhu Koda to the chief minister’s chair between 2006 and 2008, the Congress had almost sealed Jharkhand’s fate as the basket case of the east, making it the poster state of mining scam fuelled corruption. But now, in a Grand Alliance of Opposition parties, namely, the Hemant Soren-led JMM, Babulal Marandi’s JVM and Lalu Prasad’s RJD, the Congress has found a spring in its step; so much so that it can now even dare to give a spin to the BJP’s masterstroke of unleashing Modi’s crowd-pulling credentials.

“We are looking at nine to ten seats for the alliance,” said state Congress chief Ajoy Kumar. That’s something coming from a party that did not have a single Lok Sabha MP from the state.

This optimism is based on both arithmetic as well as political positioning on key issues. Regional satrap Hemant, the son of Shibu Soren, agreed to stitch together an alliance fairly early on in the campaign: Congress got the lion’s share with seven seats, the JMM four, JVM two and the RJD one with the understanding that come Assembly elections later in the year, the JMM would lead the pack. Save Chatra, where the RJD has queered the pitch for the Congress by fielding a Lalu confidant, the gathbandhan has stuck to the formula.

Union minister Sudarshan Bhagat, who is seeking reelection from Lohardaga, calls it an alliance of convenience, but sticks to national security while campaigning. “A party that seeks proof of damage inflicted on the enemy during the Balakot air strikes is trying to demoralise the spirit of the armed forces,” he tells an audience of 50 men and women at an ex-servicemen’s welfare organisation in neighbouring Gumla. Elsewhere, he is having to explain the state government’s controversial move to amend age-old tenancy laws (Chhotanagpur Tenancy Act, Santhal Pargana Tenancy Act) that protect tribals’ ancestral property. “It’s a closed chapter,” he says about the attempt to dilute provisions of the laws that prevent the sale and transfer of tribal land to non-tribals.

Sudarshan is pitted against another Bhagat, the Congress’s former state party chief Sukhdeo, who managed to win his Assembly segment despite the Modi wave of 2014. The Congress senses blood this time, Ajoy Kumar attributing it to a “groundswell of tribal anger”. Maybe, that’s why Modi was there too, addressing a gathering of a lakh supporters five days before voting.

Chief minister Raghubar Das may have overreached by trying to meddle with tribal land laws to push industry, but he did begin on a right note when he assumed power in 2014-15 by setting up the building blocks of the administration. Sectorwise policies were framed, the number of departments was pruned, a single-window system of clearances was set up, courtesy Rajiv Gauba, who was Jharkhand chief secretary before he returned to Delhi as Union home secretary. Subsequently, the state also went on an aggressive investment seeking drive, holding roadshows and more than one mega investor summit to generate a slew of MoUs. Today, among the big-ticket projects being tom-tommed are the Rs 6,500-crore fertiliser factory at the site of the scrapped Food Corporation of India plant in Sindri (Dhanbad), NTPC’s Pakri Barwaddi coal mines, NTPC’s Rs 19,000-crore investment for a 4,000MW power plant at Patratu (Ramgarh) and the Adanis’ 1,600MW power plant coming up at Godda with a promised investment of Rs 14,000 crore. Not all of these have gone off the ground without controversies. Recurring agitations over faulty land acquisition have often turned violent, leading to loss of lives.

“The poor implementation of good policies in Jharkhand seems to have let down Modi,” said Deepak Maroo, president of the Federation of Jharkhand Chamber of Commerce and Industry, pinning the blame on the non-performing bureaucracy. “Land acquisition processes weren’t followed because of corruption at the level of circle officers, which ultimately lent the state a bad name,” he added.

The Telegraph

In September 2016, social concerns peaked over malnourishment deaths — at least 18 since then which the government contests; PDS anomalies over Aadhaar linkage issues; crib deaths at a state hospital; and lynchings over alleged cow slaughter — as many as 13 since 2016 — the fallout of which was aggravated when Union minister and Hazaribagh MP Jayant Sinha felicitated some suspects with garlands and then apologised in the face of national outrage.

Sinha called it a “closed chapter”, but clarified that he has always stood for the rule of law. “I am completely against mob violence, completely against lynchings… I have total respect for the law,” he told The Telegraph while campaigning in the interiors of Hazaribagh. “People who are for us vastly outnumber the people who are against us… There is out and out support for Narendra Modi as our PM. The vote is a foregone conclusion in our favour,” he said.

Yet, some BJP candidates are having to counter the undercurrent of social disaffection that has gripped the state’s poor, especially minorities and tribals who account for around 30 per cent of the population. Former chief minister Arjun Munda, who is contesting from Khunti after elder statesman Karia Munda was denied a ticket, talks of setting up an office in Murhu, a wayside town, 13km from the district headquarters, so that local residents don’t feel left out. Arjun Munda, attempting a comeback after five years in the wilderness, knows he would have to tread carefully in the constituency that sparked a small, but significant, secessionist agitation in the name of pathalgadi, an ancient tribal custom of honouring forefathers with stone plaques. He also never forgets to criticise Rahul Gandhi. That day, he mocked the Congress president for expressing regret to the apex court over his “chowkidar” campaign slogan.

It is a measure of the harsh realities of democracy that the BJP is faced with a tough challenge in its citadel of the east. Instead of building on its much-touted “double engine sarkar”, a reference to its leadership in the state as well as the Centre, the party now finds itself facing a challenge it wasn’t quite prepared for. Unforeseen local circumstances, coupled with the genuine anger of tribals and minorities, have made it a difficult election for it in Jharkhand. A senior party leader admitted 12 could well come down to seven. Even in the state capital Ranchi, the BJP has been pushed to the corner by its sitting MP, who is contesting as an Independent after being denied a party ticket on account of his age. Ram Tahal Chowdhary is in revenge mode, planning to organise football matches, to popularise his poll symbol. Now, it remains to be seen who gets to shout “goal”.