Six in every 10 tuberculosis-affected households in India experience “catastrophic” costs, a study has suggested, indicating that the central TB control programme’s milestone to eliminate the infection’s economic distress to households by 2020 remains unachieved.

The study has found that 61 per cent of 1,482 TB-affected households sampled from four states — Assam, Bengal, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu — faced catastrophic costs, taking into account both costs during treatment and indirect costs resulting from income losses.

Health researchers typically define catastrophic healthcare costs as amounts beyond 20 per cent of annual household income, a level at which households are compelled to significantly lower their living expenses or borrow money to cover costs.

The Narendra Modi government had in 2017 announced a National Strategic Plan (2017-2015) to end TB and achieve “zero catastrophic costs” for TB-affected families by 2020 as a milestone towards achieving a five-fold reduction in TB incidence and prevalence by 2025 from 2015 levels.

The new study, published in the journal PLOS Global Public Health, has found that over half (52 per cent) of the households that experienced catastrophic costs did so even before starting treatment for TB, with a seven to nine-week gap between onset of symptoms and treatment.

“We find that employment loss and income loss pose severe challenges — in addition to the costs imposed by diagnostic delays and multiple visits to healthcare facilities to seek diagnosis,” Susmita Chatterjee, a health economist at The George Institute for Global Health who led the study, told The Telegraph.

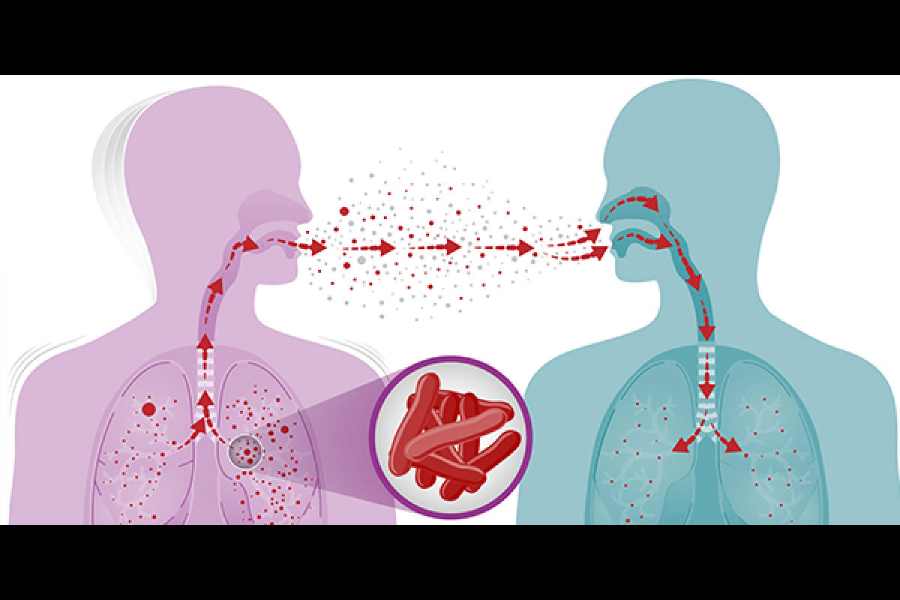

India has the world’s largest burden of TB patients with an estimated 1.93 million new infections detected in 2021. The TB control programme offers free diagnosis and treatment but multiple earlier studies have flagged diagnostic delays and the catastrophic treatment costs.

The findings by Chatterjee and her colleagues suggest that India’s proportion of TB-affected households that face severe economic hardships is significantly higher than between 7 per cent and 40 per cent as estimated by earlier studies since 2020.

Their study covering the period 2019-2022 represents the longest follow-up of TB-affected households from different population groups — general population, urban slum residents and tea-garden workers in Assam, Bengal and Tamil Nadu — the follow-up continuing for months after treatment.

The government has since April 2018 offered nutritional support to TB patients — through a payment of ₹500 per month for each patient throughout the treatment duration that typically lasts six months in drug-sensitive TB without complications.

The new study has suggested that poor households need much more through the infection. It has found that 23 to 44 per cent of households had to borrow money to manage TB-related expenses, while about 15 per cent urban slum residents and 10 to 14 per cent of general households and tea-garden households sold their belongings.

“Treatment is free, they need money to travel for the daily treatment or to buy extra food such as eggs or fruits that they’re encouraged to eat and sometimes to manage side effects of treatment,” Chatterjee said. “And families spend a lot of money on diagnosis even before treatment.”

Some proportions of households across all income quintiles — from the poorest to the richest — faced catastrophic costs.