When Ruchita Chandrashekar decided to move to Bangalore in November for a new job, she thought she had the perfect plan for avoiding the problems that come with house hunting as a single woman in India.

She would find an apartment with a married friend whose husband was working in Paris — and they would say they were sisters. They were both professionals, in their 30s, with a sizable budget. Alas, they were still women unattached to men.

Brokers asked if they could promise to never bring men over. To never drink. To never, really, have a room of one’s own. Several places they thought they’d secured fell through — into the arms of families.

“Sometimes, this is a nice life,” Chandrashekar said over a light lunch in Bangalore, where she works in organisational development for a tech company. “But then you meet all of these structures, like your landlords.”

“There is always something to fight for,” she added. As they delay or reject marriage and live on their own, single working women like Chandrashekar are making their case for greater freedom from India’s conservative norms.

While they are a sliver of the country’s total population, they still number in the tens of millions, and their often infuriating quest for housing is a barometer for the country’s promises of modernisation and rapid economic growth.

For years now, Indian women have been racing into higher education, with government figures from 2020 showing they now enroll at higher rates than men. And yet India is still one of the most male-dominated economies in the world.

Just under 20 per cent of Indian women engage in paid work, compared with 62 per cent of women in China and 55 per cent in the US, according to World Bank figures.

Many women work in informal jobs in an economy that has failed to produce enough formal work for a growing population of 1.4 billion people.

The unemployment rate is currently above 8 per cent, according to data released this month. But if women were represented in the formal workforce at the same rate as men, filling some jobs and creating others, India’s economy could expand by an additional 60 per cent by 2025, according to some estimates.

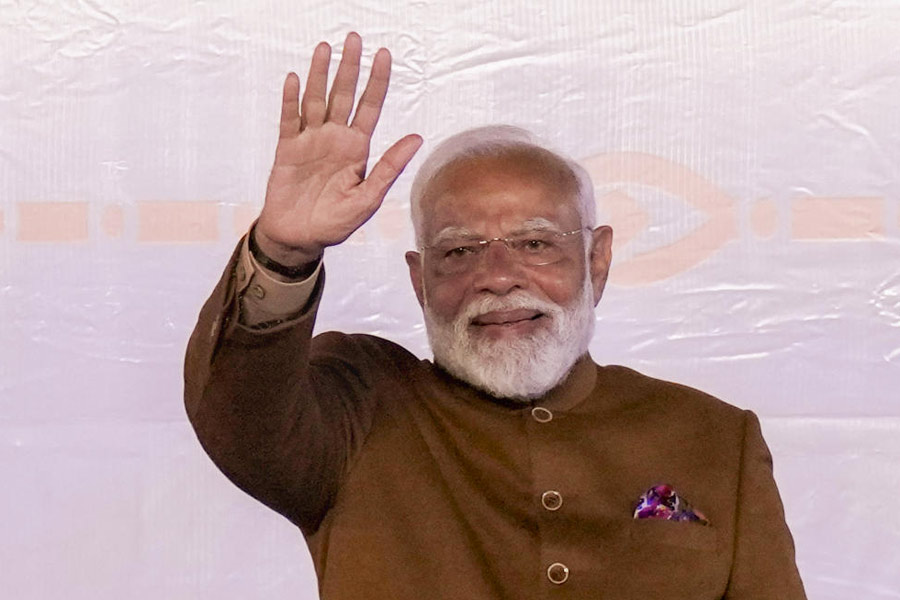

With this in mind, Prime Minister Narendra Modi asked state labour ministers in August to come up with ideas for harnessing women’s economic potential. A good place to start, many say, would be the obstacle courses of life that exist for women outside the office or factory.

Working women living independently in India’s cities — whether single, divorced, widowed or living separately from their partners — face endless sermons from strangers. They pay more for a narrower selection of housing.

Worried about sexual violence, friends track one another by phone until they reach their destinations. And still, they endure men who expose themselves at bus stops or landlords who, if they don’t reject them, impose curfews and then waltz into their rented spaces unannounced.

“There is no lack, no dearth of aspirations in women, but still, our social and cultural shackles are so strong that they are curbing their freedom,” said Mala Bhandari, founder of the Social and Development Research and Action Group, which studies gender and conducts training for businesses.

Amartya Sen, the first Indian to win the Nobel in economics, has called India “the country of first boys”. He argues that the nation has made high-achieving men a cultural obsession, at the expense of nearly everyone else. Women have only recently entered the fray in large numbers.

The economic liberalisation that started in 1991 led both to more female university students and more encouragement for them to study away from home. Many started out in single-sex “paying guest”, or PG, hostels loosely attached to colleges — private or government housing with shared rooms and food provided by adults seen as secondary parents.

Often, women like Chandrashekar’s mother — who set aside a law degree when she graduated and quickly married — pushed their daughters away from rigid ideas of gender.

As birthrates have fallen to two children per woman in India, fathers have also invested more in girls’ education, with a mix of pride and fear. The 2012 gang rape and murder of a 23-year-old physiotherapy student in Delhi led to new laws and programmes for protecting women.

But by the rawest of measures, they have had little effect: In 2021, the last year for which data is available, India recorded 31,677 rape cases, up from 24,923 in 2012. In interviews with more than a dozen unmarried working women in greater Delhi, Bangalore and Mumbai, safety emerged as the top concern in choosing jobs and housing.

They did everything possible to shrink the distance from home to work. And they all had torments to share: being slapped on the rear by a man on a motorbike; fleeing a drunk taxi driver; running away from men howling for attention.

Single professionals from 23 to 53 said they felt more vulnerable because men saw them as sexually available, if not immoral.

“They think women should live according to a certain way,” said Nayla Khwaja, 28, who works in communications in Delhi. “And if somebody is doing something out of that way, then that is something to notice.”

Many landlords see renting to single women alone or in groups (and single men, to a lesser extent) as a risk — to the stability of families, to the reputations of neighbourhoods. Dinesh Arora, 52, a broker in middle-class South Delhi, said few landlords rent to single women because they oppose their separation from family, or fear judgement if something goes wrong.

“When you live in a small community, everyone worries about what’s happening next door,” Arora said. “When you see on the news all the crimes taking place, you worry.”

Among those who lease to women, higher rents, surveillance and paternalism are often the urban norm. Even if they rise at work, many women end up back in paying guest hostels, with curfews at 9 or 9.30pm and bans on drinking, smoking and male guests.

A renter’s religion, sexual orientation or caste can limit options even further. Khwaja, who is Muslim, recalled a night when she was out late filming an event and the hostel where she was living in Delhi wouldn’t let her back in. “It was just 10.30,” she said.

After Susmita Kandadai, 27, paid for an apartment in Pune, the landlord’s lawyers sent her a lengthy agreement demanding that she never allow visitors, including relatives, and always be home by 9pm. She refused and found herself in the landlord’s kitchen — he lived downstairs — receiving a lecture from his wife about clothing choices and missing values. She fled a few days later, after the landlord grabbed her by the arm during another harangue.

“I just got so scared,” she said. “I moved right out of there and slept on a friend’s couch.”

New York Times News Service