MV Tamim Aldar

Mishra and Lobo’s ship has been anchored 45 km from the port of al Hamriya since November 2017. The ship’s assignment was to carry rocks from Fujairah, an emirate on the east coast of the UAE, to the port of Al Faw in Iraq.

During the assignment, the ship’s main engine died. Mishra had joined the vessel in October 2016 and had asked the company to relieve him in August 2017. He was told to make one last trip – the one that is yet to end.

After the engine died, Elite Way Marine Service told the sailors to drop anchor and wait

for further orders.

“So, we anchored. The company left us here and didn’t send anyone to repair the fully loaded ship. It was left as it is,” Mishra told this website in a WhatsApp message when patchy internet service was available to the ship.

The sailors slowly found out that it wasn’t just they who were asked to drop anchor, but eight other vessels.

After receiving no salary for a few months, realisation dawned that they had been abandoned in the sea. “We registered a complaint with the FTA (the Federal Transport Authority). We were the first,” Mishra said.

After receiving complaints from different vessels, on June 5, 2018, the FTA banned Elite Way Marine Services from sailing any vessel.

Mishra said the company stopped responding to their pleas after that. After the sailors had anchored, the company used to send them food, water and fuel. After the ban, it stopped.

Forty sailors, of them 31 Indians, on eight abandoned vessels in the Gulf waters were stranded on board and waiting for their pay for months.

The wait

A week ago, Mishra and Lobo sent out an SOS email to the FTA and the Indian consulate in the UAE. They said their fuel supply would probably last another 10 days and after that the vessel would be in “blackout”.

An unlit vessel in the middle of busy sea routes at night is disaster waiting to happen.

In one of the voice messages to this website, Mishra said: “During the day it becomes too hot in the 40 degrees plus Gulf heat. With no electricity, the air conditioner doesn’t work either. It is impossible to stay out in the sun or inside in the heat.”

Unable to withstand the conditions anymore, the two set out in a lifeboat on Saturday morning for the port of Umm Al Quwain, about 50 km northeast of Dubai.

But before they could make it to Umm Al Quwain, the coast guard caught them. After talking to the ship’s owners and confiscating the lifeboat, the authorities ordered the duo to return to their vessel. After November 2017, this was the only time the two had set foot on land – the coast guards’ office.

By Saturday evening, Mishra and Lobo were back in floating oven that Tamim Aldar had become. They had run out of food and oil.

“The coast guards told us that they will put us in jail for two years. Even if they said that casually, we took it seriously and returned. Otherwise, we wouldn’t have left the port,” Mishra said.

The coastguards assured the sailors that the Tamim Aldar would be tugged to a port by Monday or Tuesday. “The company has been lying to us for two years now and this might be another such assurance,” Mishra said. “We’ll see. It has all been a lie. All they did was lie to us since we got here.”

Bowerman, who was aware of the duo’s trip to the port, said: “We advised them to remain on the ship but how could they without any power.” He added: “I do have some sympathy for the coastguards. No one wants a ship of that size unmanned and unlit in a shipping lane.”

Back home

18 months ago, like the Tamim Aldar, another UAE cargo ship called the MV Azraqmoiah was told to drop anchor in the Gulf waters. This ship too belonged to the Elite Way Marine Services.

The 42-year-old ship’s captain, Ayyappan Swaminathan from Kumbakonam, was in charge of a crew of 10 and after many rounds of haggling got 80 per cent of his salary dues of $74,000 and returned to India in mid-June.

Other crew members, who could not hold out for that long, left with 40-60 per cent of their pay. “It was a very dark time in our lives. Very dark,” Swaminathan said.

Like Mishra, Swaminathan’s ship was carrying building materials from the UAE to Iraq when the ship was abandoned off the coast of Ajman.

Swaminathan sent a notice to the FTA on April 1.

“I had to send the notice. It was like an alarm. I sent it to Captain Abdullah (of FTA), the Minister of External Affairs. I sent it to all who could help,” he said.

He said that soon after, in an act of revenge, the ship’s owner started delaying supplies and eventually stopped sending provisions to force the sailors to leave the vessel.

After returning home, Swaminathan said, he realised how much his family had suffered because of pending loans, mounting debt and no source of income.

“They (the owners) spoilt our lives,” he said. “They sent us nothing, nothing at all. Even during Ramazan, I asked the (Indian) embassy to get something for our two fasting Muslims, an Indian, Rajib Ali and a Sudanese, Ibrahim. I didn’t ask the owner,” he said. “I don’t think he is a Muslim, given the way he negotiated with us during Ramazan while we struggled for food and water.”

Even if someone thought of leaving the ship, they couldn’t for reasons other than the money that was due to them. Swaminathan said their passports were taken from them by coast guards who came on board.

Like Swaminathan’s family, Mishra’s wife struggles to make ends meet. Mishra’s monthly income of $2,500 was once enough to run a joint family - his wife and kids who live in Mumbai and his brother’s family and parents who live in Kerakat, Mishra’s home town in Jaunpur, Uttar Pradesh.

“Please try and bring him back,” Mishra’s wife Vineeta pleaded over the phone. “Ghar ki condition bohot kharab hai (our home is in a terrible condition). How long can one depend on brothers or friends for every small expense. I’ve been hearing that someone or the other has returned. It’s almost three years now. When will he return?”

Mishra has a nine-year-old son and a three-year-old daughter. When he left for Dubai, Mishra’s daughter was just nine months old.

“My daughter won’t even recognise me. She won’t know who her father is. I see her only in photos on WhatsApp,” Mishra said.

Lobo said his family was “getting by somehow with borrowed money from his in-laws. My wife is struggling to pay for my 14-year-old son’s education,” Lobo said in a WhatsApp voice message.

Help in the high seas

Mishra and Lobo seemed grateful for the help they and other stranded sailors received from the International Seafarers' Welfare and Assistance Network (ISWAN). The network sent $1,250 to their families.

A UK-based non-profit, ISWAN looks after the welfare of seafarers, including abandoned or stranded ones or their families struggling in case of unfortunate incidents.

Since 2004, 336 vessels have been abandoned, according to a database maintained by the International Maritime Organization and the International Labour Organization. These vessels had 4,866 seafarers on board worldwide.

In 2017, there were 55 reported cases of abandonment, and in 2018, the total number of reported cases was 44.

“I know it is a horrible situation when you have to depend on somebody else,” said Chirag Bahri, regional director of ISWAN and a former seafarer who was held hostage by Somali pirates on a hijacked vessel in 2010. “It affects your dignity. You are on a vessel, you have come to work and now you are dependent on somebody else for everything.”

The consul-general of India and non-profits have been in touch with the seafarers throughout on Twitter and WhatsApp.

On multiple occasions, as confirmed by Swaminathan and Mishra, the Indian embassy sent food, water and medicines to the vessels.

The Indian consulate in the UAE said they do help stranded Indian sailors and confirmed that they knew about the case of stranded sailors of Elite Way Marine Service.

When asked about Mishra and Lobo, Vipul, the Indian consul-general in Dubai wrote: “The two sailors about whom you have asked the question are in the Tamim Aldar ship which is not on the port but in the anchorage i.e. nautical miles from the port. To send them provisions, a boat needs to be hired which becomes fairly expensive unless you are serving several ships. Nevertheless, we have ensured that provisions reach them through the owner. At least on two occasions we have sent the provisions ourselves. Government of India would not want any Indian sailor to be abandoned anywhere but you need to appreciate that neither the ship is of Indian flag nor is it in the territorial jurisdiction of India. In such cases, we have to work with Government of UAE and depend on them or the flag state.”

The consul general added: “We are currently negotiating their unpaid dues with the owner.”

Bahri said the seafarers choose to stay on board because they are unaware of their rights. “The maritime lien on the vessel doesn’t simply go away if the seafarer has signed up on the ship. Seafarers still have the right to ask for wages if you have come back home,” Bahri said.

Off the coast of Dubai, 45 km into the sea, is the cargo ship MV Tamim Aldar. In it are two Indian sailors who had not seen a shore for over 20 months.

When they did come on shore in a lifeboat on Saturday, the UAE coast guard reportedly sent them back to their ship.

Why the Indian sailors are out in the sea for so many months is a long story. It has a cast of hapless immigrants, bankrupt vessel owners, worried rescuers and families in severe distress and debt back in India.

Two points are central to understanding why the two sailors – 34-year-old Vikash Mishra from Jaunpur and 49-year-old Arasu Lobo from Tuticorin – are bobbing in their dark vessel out in the sea for months.

The first is that Mishra has not been paid his salary for 28 months and Lobo for 22 months by Elite Way Marine Services, the company that abandoned eight vessels in the Persian Gulf because after it allegedly went bankrupt. Elite Way Marine Services could not be reachd for comment despite multiple attempts by this website by phone and email. (The report will be updated when a reaction is received from the company).

Second, Mishra and Lobo initially did not want to leave the vessel like many other sailors employed in Elite Way Marine Services’ other ships because they wanted to hold the ships as collateral for their salary dues.

“I think if you are a seafarer, the last thing you want to do is to leave the vessel with nobody on it. It’ll be dangerous and you then would be responsible for leaving the vessel. They (Mishra and Lobo) are in a busy part of the Gulf. If something happens, they may get into serious trouble,” said Andy Bowerman, who works with the Mission to Seafarers, a religious non-profit that provides aid and addresses human rights issues affecting seafarers.

“But many sailors stayed on board initially because the only collateral they had was the vessel. They had no other bargaining tool. ‘We have your vessel, give us our money’,” said Bowerman, trying to explain the situation over the phone from Dubai.

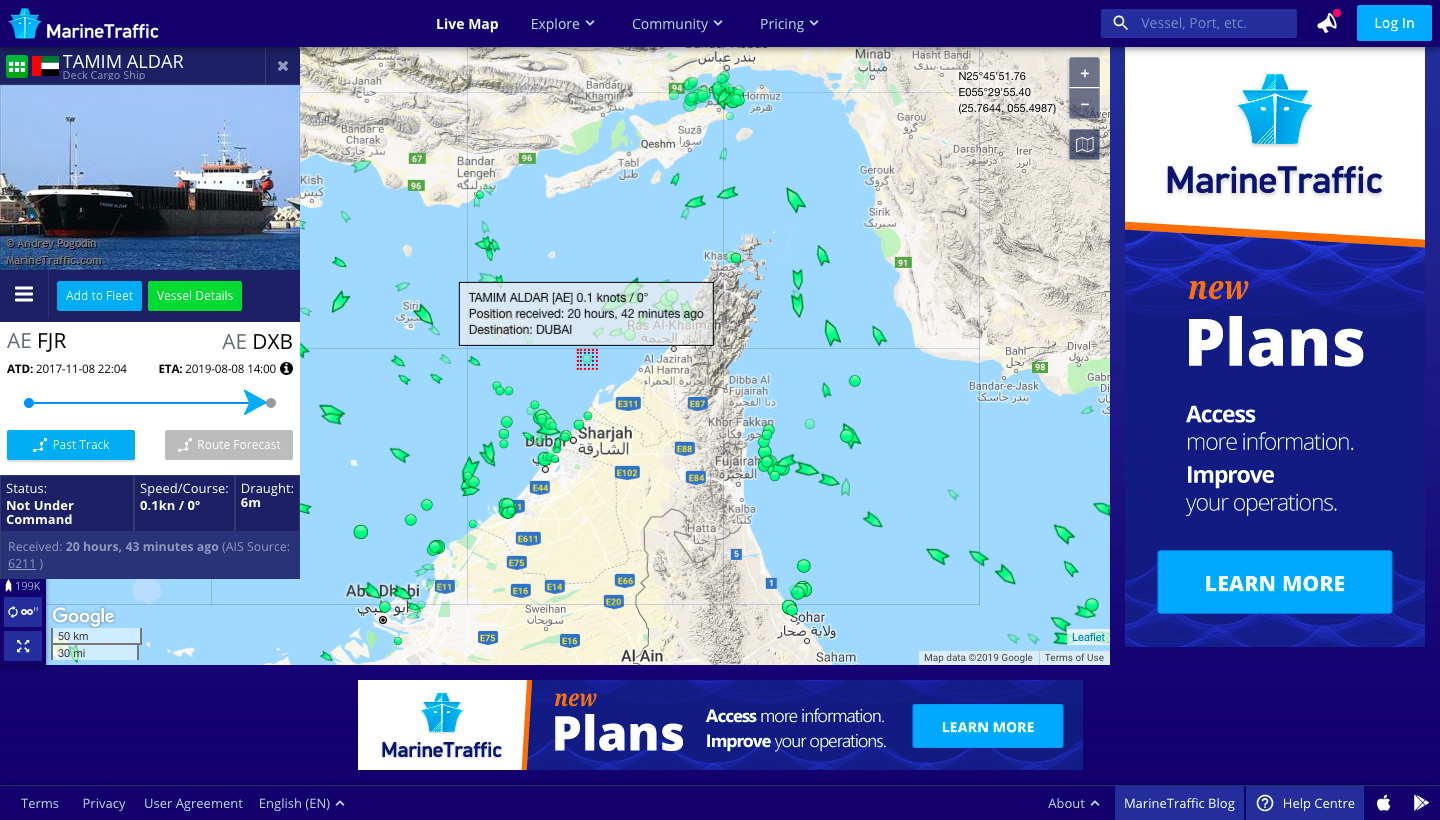

The location of the MV Tamim Aldar on a marine traffic monitoring website Source: www.marinetraffic.com

Inside the MV Tamim Aldar Source: Photos sent by sailors by WhatsApp