The out-of-a-catalogue living room of the south Calcutta apartment seems to be holding its breath. Aquamarine sofas, carpets, runners, wood and silver and glass, porcelain white roses at attention, nostalgia on the walls, canvasses full of faces, a glass bowl upturned, a glass bowl overturned, both empty, tempting poetry. The coffee table laden with a neat stack of books. I merely lean over to read the title of the top one, but the mango tree sticks its head through the window like a leafy reprimand. A sparrow hops from the window sill onto a waiting tea trolley and then again from trolley back to sill, as if to establish its guardianship. I glance at the book title hurriedly — Again — and turn away; this time a coconut tree grins cheekily from one of the windows to my left. And then someone turns on the fan and the room begins to breathe. Seconds later a voice floats in, followed by a slight figure; greetings, a friendly tirade, and just like that I find myself caught up in the vortex of singular hospitality, swept out of the aquamarines and deposited in Mahua Moitra’s scarlet sun verandah.

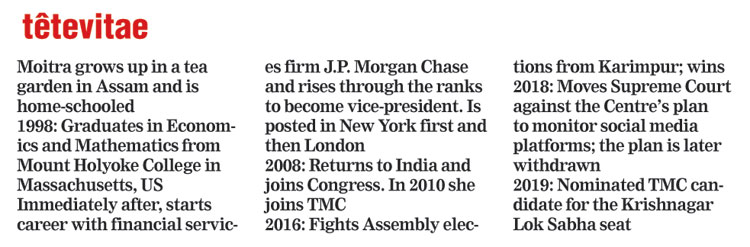

The day before, the Bengal chief minister and Trinamul Congress (TMC) boss, Mamata Banerjee, has announced her list of candidates for the 42 Lok Sabha seats. TMC’s Karimpur MLA, Mahua Moitra, whom I am meeting that morning, is Banerjee’s pick for Krishnagar. She is to leave for campaign duty in a day, and this day is for prep, packing and last-minute meet-ups. I tell her that social media is all agog, hailing her as she-who-showed-the-middle-finger-to-Arnab Goswami on national television — a show from 2015 — and she squeals: “I did not.” (Moitra herself is not on social media.) So is she saying she is not guilty as charged? But reams have been written about “fingergate”. “I know, I know,” says Moitra. She elaborates, “But I did not do it. I move my hands a lot when I talk, that time too I was gesticulating, but in the freezeframe it looked otherwise. Someone noticed and put it out and it just caught on. I did try to clarify but it was obvious people were cashing in on the opportunity to get back at someone and it was not me; besides I had work to do.”

Talking about work, Krishnagar is not going to be easy. The BJP is betting on this constituency. Moitra takes the question but ignores the BJP bit, as if it were not a factor worth weighing even. “Nothing’s easy, but as I see it, if I can’t crack this I shouldn’t be in this business,” she replies. The investment-banker-turned-politician rolls out whole spools of thought, Shankar Mahadevan’s Breathless style; there are digressions and platitudes but, as with all sharp speakers, one doesn’t mind them. Words pirouette, passions climb as does her pitch, and there is a lot of thumping of the wooden handrest of the sofa.

For the next several minutes, she keeps talking about Krishnagar, about how life comes full circle. Her father’s family is from those parts and Ila Pal Choudhury, Congress MP from Krishnagar in 1968, is a relation — but she is not referring to those associations. Krishnagar was the seat Congress wanted her to contest from, when she first came back to India from London in 2008-09 and joined the party. That year, Congress had entered into an alliance with Mamata Banerjee, who subsequently did not release the Krishnagar seat.

Moitra says, “I spent over three months going from booth to booth in this very seat as part of Congress’s booth-building exercise under the Aam Aadmi Ka Sipahi programme [a grassroots effort].” Krishnagar 2009 was a missed opportunity, but Moitra’s first electoral foray was from Karimpur, also in Nadia district, and an hour-and-a-half from Krishnagar. And what was it like working with Rahul Gandhi? She replies, “I don’t even remember it. Aam Aadmi Ka Sipahi was a very good experience.”

We discuss the impending elections and I ask what she thinks is at stake in 2019. Without batting an eyelid she erupts, “I have never seen the idea of India being threatened. I knew the India I grew up in. I knew the India I came back to. I know the India I want to preserve. This is the first time when we are fighting not to remove a government, we are not fighting to remove a person, we are fighting to remove the very anti-thesis of the idea of India.” She pauses and then adds, “This is a seminal election; possibly the first such since Independence. And I am honoured to be part of it.”

She talks impassionedly about the work she has done in Karimpur — the fund-hunting, the system, the processes. She is effusive in her praise — credits the public works department, the district magistrate, the panchayat department. “I have done over Rs 150 crores worth of work in three years in one Assembly constituency… In Nadia district, everyone knows that TMC has done good work,” she adds.

And yet her detractors never tire of pointing out that she and Banerjee inhabit very different images, chalk and cheese. (Much has been written about the Bobbi Brown eye pencil in her bag and that Carnation lip colour, the brands she favours.) When she quit Congress, what was it that made her choose to work with the TMC chief? She replies haltingly, making obvious the emphasis on every word: “I would rather be a nobody with Mamata Banerjee, than be a somebody with Congress.”

But there have been reports saying Didi wanted to be rid of her. A 2016 news report quotes an anonymous top TMC leader saying Moitra was given the Karimpur seat for this very reason. He said, “Good thing if she wins, even better if she loses.” Says Moitra, “In this party, from the day I have joined, I have been on an upward climb. If there was a situation like that, I would have been demoted.” But is she aware of these rumours? “Not really,” says Moitra, “I don’t care. I have survived on a trading floor. I have the skin of a rhinoceros.”

The Telegraph

The Krishnagar ticket, she says, is a vindication of sorts. “I am glad it took me 10 years to get it. Had I got it then, people would have said: ‘She has parachuted in, she is using push, pull, shove.’ Now they can’t… My trajectory has vindicated me. And I am immensely grateful to the boss. She gives you the platform. It is exceedingly empowering. I have worked with fantastic woman bosses. I have lived all over the world. Let me tell you she is up there.”

I want to know about her growing up years. The reports that abound would have us believe that all was tabula rasa till she went to Mount Holyoke College in the US. Moitra talks fondly about the growing up years in a tea garden in Assam, the experience of being home-schooled. A wasp enters the sun verandah at this point and suddenly she is on her feet and calling for help: “Isko hatao. Bukhaar ho gaya tha pichhle baar jab kata.” The next minute she apologises profusely, continues the reminiscing — buying a toy a year from Paragon on Park Street, buying books at Bingsha Shatabdi, the Calcutta bookstore that sold Soviet and Russian literature, reading Asterix. She says, “We always had plenty to eat, but we were never into any display of wealth. People laugh about my bags and fashion, but it is only when I started working that I did what I did. That is also part of me. I don’t hide that.”

I recall a news report from 2016 according to which the moment her candidature from Karimpur was announced, all went scurrying to find her luxury digs. Moitra says it was an outright lie, an apology was tendered in due course. But what is the problem even if it were true? One might be used to certain things, and it wouldn’t necessarily take away from the work? Says Moitra indignantly, “If I had done as much I wouldn’t care, but I hadn’t.” She quotes from the Gita: “The unreal never is, the real never is not.” Talking of realities, she tells me how that year she campaigned on foot across Karimpur and how the CPM joked, “Mohila ki steroid khae… Is that woman on steroids?”

Wrapping up, I want to know what kind of politician she is never going to be. She says, “I think I will always be a conviction politician, not a consensus politician. And that’s quoting Mrs Thatcher. When you feel for something you go out and do it. When the recent air strikes happened, everyone said this is not the right time to ask questions. We just went out and said this is not adding up.”

I think she is done and I start to put away the notepad, when she speaks up again, “And I don’t ever want to be a kind of politician people can raise a finger at. I don’t mind if they find fault with me on the basis of personality traits. But I don’t want anybody to be able to say she is corrupt or is inaccessible to her constituency or never cared for people. I am still very idealistic about politics. Every day I wake up and I am happy. I hope I die a politician and that I carry this idealism with me.”