A Karnataka government decision to divert water from the river Sharavathi in Shimoga to parched Bangalore, 430km uphill, has evoked stiff opposition from environmentalists and Shimoga residents.

Opponents of the proposal argue it’s an injustice to Shimoga’s people, themselves facing a “drought-like situation”, and environmentally suicidal because it involves linking two ecosystems and large-scale felling in the Western Ghats to lay the pipeline.

Chief minister H.D. Kumaraswamy recently directed the water resources department to prepare a detailed project report on diverting 30 tmcft (thousand million cubic feet) of water from Linganamakki, the main storage dam on the Sharavathi.

This led to the formation of the Sharavathi Ulisi Horata Samiti (Save Sharavathi Movement), which has called for a shutdown in Shimoga on July 10.

“We will never allow this diversion of water when Shimoga is reeling under a drought-like situation,” Akilesh Chipli, an environmentalist, told The Telegraph on Saturday. “Even the Sharavathi is drying up.”

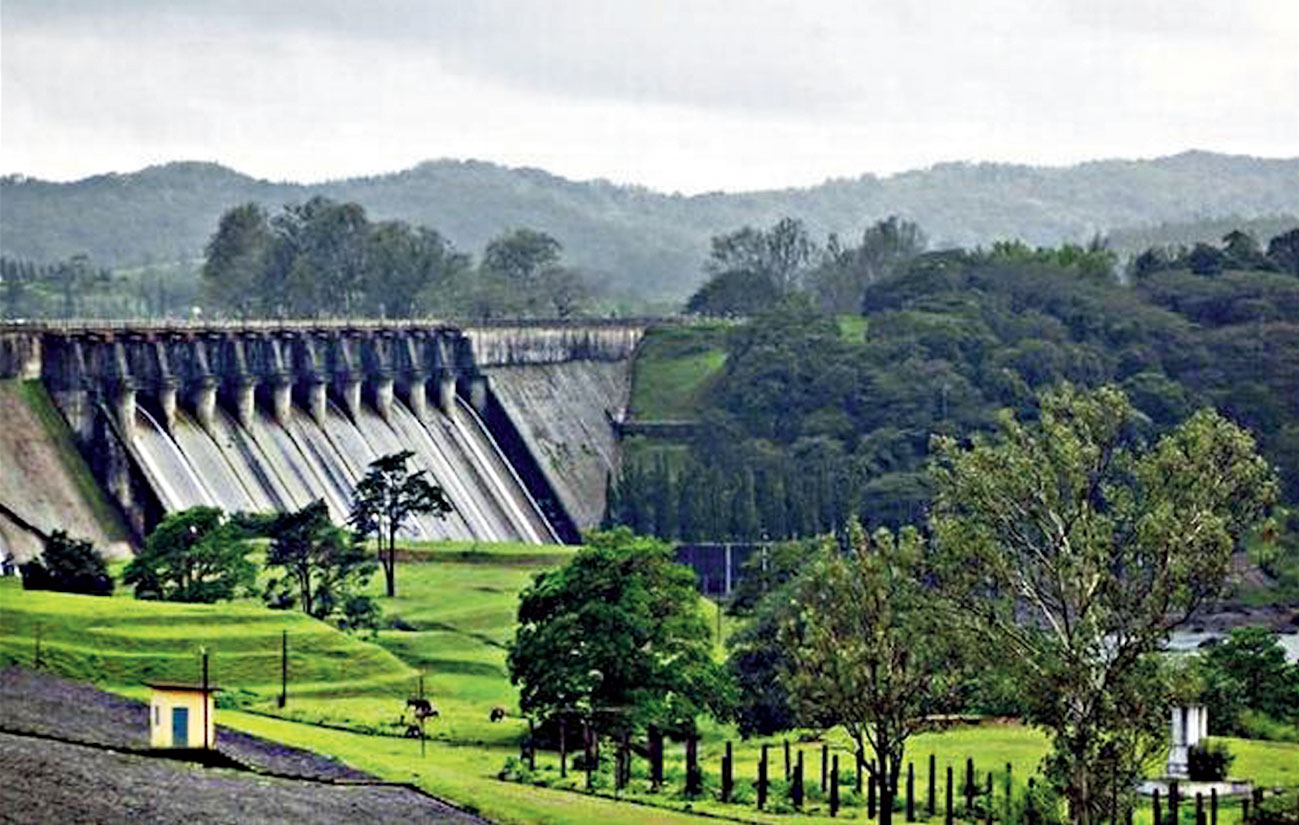

The Linganamakki dam in Shimoga from where the Karnataka government proposes to draw a pipeline to take water to Bangalore.

The Karnataka State Natural Disaster Monitoring Centre has reported a 56 per cent rainfall deficit in Shimoga.

Chipli questioned the logic of laying a 430km pipeline uphill to Bangalore at a huge cost when “it would mean clearing large tracts of forests in the Western Ghats, which could eventually affect rainfall”.

Bangalore-based activist Vijay Nishant has started an online petition on change.org against the government proposal.

“What Bangalore is facing today is the result of gross mismanagement of its water resources. We (in Bangalore) get enough rain to harvest at least 16 tmcft of water each monsoon. But instead, we cement all our courtyards and let the rainwater flow out through drains,” he said.

“We have overexploited Bangalore’s groundwater to the extent that most of the tube wells are dry or are drying. The first thing our government should do is decongest the city by providing facilities in other parts of the state for companies to move to.”

Nishant agreed that Bangalore, bursting at the seams with 1.2 crore people, needed more water but stressed

that “it is ethically wrong to rob another district of its meagre water resources”.

R.S. Deshpande, former director of the Institute of Social and Economic Change, echoed the charge of Bangalore wasting its water through poor management.

“Another ecosystem should not pay the price for the mismanagement of our resources in Bangalore. It would be like financing a person who has lost everything through gambling,” he said.

Deshpande, an expert in agrarian economics, described the government proposal as “unscientific”.

“Management of resources should be in situ (within the ecosystem). By connecting the two water sources, the government will be harming the ecosystem of Sharavathi,” he said.

“The extent of the damage may not be imaginable today, but it would be irreversible by the time we face it.”

Deshpande urged private and public sector companies in and around the city to do their own rainwater harvesting and water management. He cited the example of the Karnataka State Natural Disaster Monitoring Centre headquarters, which harvests water and solar energy to meet a substantial part of its needs.

As Bangalore gets more parched with every passing year, residents of city areas that are yet to be connected with water pipelines are up in arms against the authorities.

“We are yet to get piped water in spite of paying for it. While apartment complexes across the road in Bellandur have water connections, the authorities make excuses when we approach them,” said Arindam De, resident of the Mantri Flora apartment block in

Sarjapur, a newer part of the city.

De and other residents buy water from private operatives, who charge exorbitant rates.