When 78-year-old V.J. Emmanuel died of old age on Wednesday evening, his passing received scant attention even in his village of Koodalloor in Kerala.

To most of the villagers, the retired English professor from Kuriakose Elias College at Mannanam, near Kottayam, was little more than an ardent preacher for the Christian sect Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Only a handful remembered him as the petitioner who won a landmark judgment from the Supreme Court on August 11, 1986, that defended the Constitution’s Article 19(1)(a), which guarantees free speech and expression, and Article 25(1), which upholds the right to practise and propagate one’s religion.

The judgment had upheld Emmanuel’s claim that forcing someone to sing the national anthem infringes on certain fundamental rights enshrined in the Constitution.

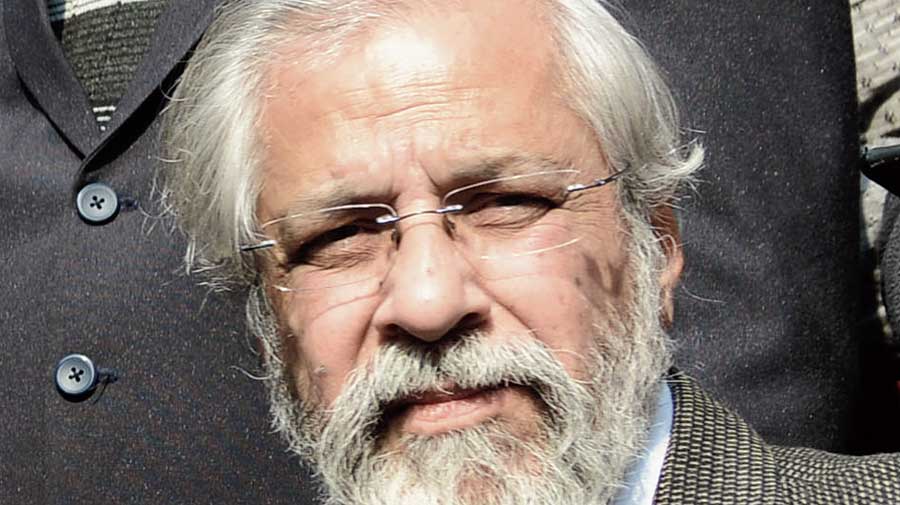

V.J. Emmanuel Sourced by The Telegraph

The court had granted protection to three of Emmanuel’s children who had not joined in the singing of the national anthem at their school at Kidangoor in Kottayam.

Thirty-four years on, the Bijoe Emmanuel vs State of Kerala judgment, delivered by the bench of Justices O. Chinnappa Reddy and M.M. Dutt, continues to be cited in legal and political circles whenever the freedom of expression or religion faces a threat. To jurists, the verdict remains one of the pillars of free speech in India.

Four years ago in 2016, the case and the verdict had become part of the larger discussion when the apex court directed all cinemas to play the national anthem before the start of screening, and ruled that those present “must stand up in respect” to “instil a... sense of committed patriotism and nationalism”.

However, in 2018, the top court, after a similar submission by the Centre, made playing the national anthem in cinemas optional and exempted disabled persons from standing up.

The 1986 judgment, while ruling that joining in the singing of the national anthem was not compulsory, had noted that standing for the anthem was appropriately respectful but refrained from making it mandatory.

After winning the legal battle, Emmanuel had sent the three children to school for just a day. After that, he decided that none of his seven children – the eldest a college student and the youngest not yet in school – would have anything to do with formal education.

“At the morning assembly, the students sang the national anthem Jana Gana Mana daily. We used to stand respectfully but preferred not to sing the anthem. For us, singing the anthem of any country is against the tenets of our religious faith,” Emmanuel’s daughter Bindu said.

“Our faith permits prayers only to God Jehovah. The national anthem is a prayer and there started our objection. We used to stand in respect while others sang. The school management, teachers and other students never objected to our refusal to sing,” Bindu’s brother Bijoe said.

In the beginning, there was no compulsion from the school to sing the anthem. But in 1985, a local MLA found the behaviour of Bindu, her elder sister Binu Mol and Bijoe unpatriotic and raised the issue in the Assembly. A commission of inquiry was formed and it visited the school to collect evidence.

The commission reported that the children were “law-abiding” and had shown no disrespect to the national anthem. However, the headmistress expelled the three children on July 26, 1985, under instructions from the deputy inspector of schools.

Emmanuel moved a writ petition in the high court seeking an order restraining the authorities from preventing the children from attending school. A single bench rejected his plea and a division bench threw out his appeal, prompting him to approach the top court.

“My father treated it as an opportunity to ensure clarity on the freedom of worship guaranteed by the Constitution. Education rights were only a second priority with him,” Bijoe said.

Bijoe was 15 and studying in Class X while sisters Binu and Bindu were 14 and 10, students of Class IX and V, when their school expelled them. The school, managed by the Hindu caste organisation Nair Service Society, had 11 students from the Jehovah’s Witnesses sect at the time.

The Supreme Court ruled: “We may at once say that there is no provision of law which obliges anyone to sing the national anthem nor do we think that it is disrespectful to the national anthem if a person who stands up respectfully when the national anthem is sung does not join the singing.… Proper respect is shown to the national anthem by standing up when the national anthem is sung. It will not be right to say that disrespect is shown by not joining in the singing….”

By the time the judgment arrived, the three children had lost one academic year. Anyway, the professor pulled all his seven children out of educational institutions, he and wife Lillikutty preferring to provide them with home education.

One of Bijoe’s two elder siblings was in college and the other in Class XII at the time. Bisny, the youngest of the seven, never went to school. All of them are now involved with evangelical initiatives.

Emmanuel’s eight grandchildren do not sing the national anthem at their schools but have faced no problems. While getting them admitted to school, the family had each time furnished copies of the verdict.

“The unique case and its petitioner must be remembered for ever as the country is facing the tough challenges posed by religious intolerance, hate and wrong notions of nationality. The verdict is matchless in its broader and inclusive approach,” said Dr K.M. Sheeba, writer, thinker and a teacher at the Sri Sankara Sanskrit University at Kaladi in Kerala.