A draft policy of the University Grants Commission has proposed lower-than-existing teacher-student ratios for some undergraduate general courses and more contractual teachers for professional programmes, raising fears of job losses for college and university faculties.

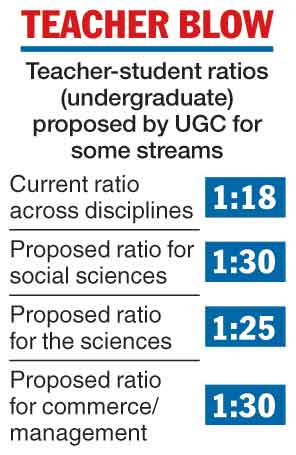

While there are now no guidelines or rules governing teacher-student ratios on campuses, the existing overall ratio across streams is 1:18. When the then UPA government sanctioned new teaching posts while implementing the 27 per cent OBC quota in 2008, it followed the 1:18 ratio, giving it a sort of official stamp.

But the draft UGC policy asks higher education institutions to achieve teacher-student ratios of 1:30 in the social sciences, 1:25 in the sciences and 1:30 in commerce, management and vocational courses. (See chart)

The UGC — the regulator responsible for quality and funding of higher education — has sought feedback from stakeholders by February 11.

Teachers’ bodies fear that the draft recommendations — while technically remaining non-binding even after possible adoption by the UGC — would encourage universities to cut teacher recruitment and eventually revoke sanctioned teaching posts to reduce costs.

“This will inevitably lead to a massive job loss for teachers and a sharp decline in the quality of education,” the Democratic Teachers’ Front (DTF), a teachers’ group in Delhi University, said in a media release.

Abha Dev Habib, DTF secretary, underlined that the government’s policy on Institutions of Eminence requires them to strive towards a teacher-student ratio of 1:10.

“Why should there be different criteria for other institutions?” she asked.

The draft policy suggests ratios of 1:15 for mass media studies, engineering and pharmacy and 1:10 for architecture and design courses, but the existing ratios in these fields are already comparable to these figures.

The recommendations are part of an Institutional Development Plan that the UGC has prepared for higher education institutions keeping in mind the National Education Policy.

For professional courses, the draft suggests that “contractual (tenured) or visiting (teachers) from the profession/industry” constitute up to 50 per cent of the institution’s total faculty requirement, the idea being to bridge the gap between academia and industry. Currently, the proportion ranges between 10 and 20 per cent in most professional colleges.

“This means that a sizeable amount of teaching workload will remain variable and many existing teaching posts will remain non-permanent,” the DTF said.

However, A.K. Bhagi, president of the Delhi University Teachers’ Association (DUTA), the official teachers’ body, said the draft may be referring to teacher-student ratios in the classroom rather than a stream or institution.

There have never been any limits or guidelines on classroom ratios, though, since a lecture theatre almost always has only one teacher while the number of students enrolled in the course may be vast.

“We will write to the UGC to seek a clarification,” Bhagi, who is from the BJP-supported National Democratic Teachers’ Front, said.

Bhagi added that the DUTA would ask the UGC not to push the proposal to allow up to 50 per cent contractual teachers for professional courses.

The document also advocates that institutions teach multiple disciplines. Habib said that an institution like the Shri Ram College of Commerce, a leader in commerce education, should not be forced to launch other streams.

“There is no rationale for the UGC to push all kinds of courses in every institution in the name of multi-disciplinary courses. This homogenisation is not helpful for institutions,” she said.

Bhagi said his understanding was that institutions would be encouraged to teach multiple streams but there would be no imposition.

While the document nudges institutions to upgrade their infrastructure, including hostel facilities, it’s silent about providing extra grants.

Habib said the regulator should clarify the situation on funding. Bhagi said that silence on funding should not be construed as denial of funding.