India’s new pledges to accelerate its moves away from fossil fuel energy over the next decade and achieve net-zero emissions by a distant 2070 represent a carefully crafted challenge to itself and to developed countries, climate policy analysts said on Tuesday.

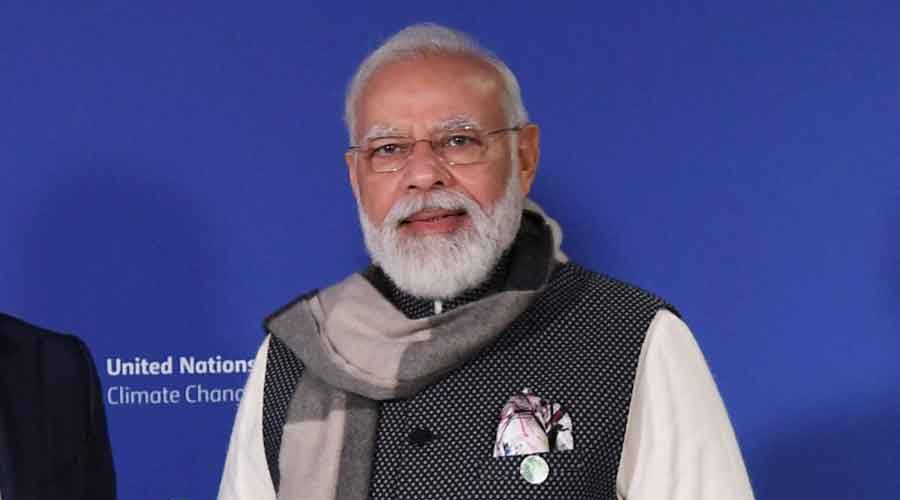

Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced on Monday India would aim for net-zero emissions — release as much emissions as it removes — by 2070 but also sought $1 trillion from developed countries, reminding them of their unkept promises of financial and technological support.

Analysts said a pledged target year for net-zero emissions was a reversal from India’s position only a week ago, but the other pledges Modi outlined in his speech at the Glasgow climate summit were in line with its stand that the focus should be on curbing emissions now.

Only last week, India’s environment secretary Rameshwar Prasad Gupta had underplayed the significance of a net-zero target year for India, saying “it is how much carbon you put in the atmosphere before reaching net-zero that is more important”.

Modi said India would by 2030 cut one billion tonnes of carbon emissions, meet 50 per cent of its energy needs from renewable energy, reduce its economy’s carbon intensity — the emissions produced per unit gross domestic product — by 45 per cent, and increase its installed non-fossil fuel energy to 500 GW from 134 GW in 2019.

“We shouldn’t view these pledges in isolation — Modi in his speech linked India’s ambitious targets with the need for more financial and technological support from developed countries,” said Anand Patwardhan, professor of public policy at the University of Maryland.

Modi said India expected developed countries to provide the climate finance of $ 1 trillion at the earliest.

At earlier climate summits, developed countries had pledged $100 billion annually to help the developing countries switch to clean energy.

“We all know this truth that promises made till date regarding climate finance have proved to be hollow,” Modi said. “While we all are raising our ambitions on climate change, the world ambitions on climate finance cannot remain the same as they were at the time of the (2015) Paris agreement.”

The Centre for Science and Environment, a New Delhi-based non-government think tank, said the targets announced by Modi were “bold and ambitious, but they will be immensely challenging to achieve”.

“By announcing these targets, India is literally not just walking but running the talk,” CSE director-general Sunita Narain said. “Given our comparatively low contributions to global emissions, coupled with the fact that our economy needs to grow and meet energy needs of millions of poor citizens, we did not need to make such ambitious pledges — but India’s pledges also represent a challenge to the already rich world to step up.”

Some analysts view the 2070 target year as driven more by political need than climate urgency. “Developed countries such as the UK and the US were putting enormous pressure on India to announce a net-zero year,” said Harjeet Singh, a senior adviser with the non-government organisation Climate Action Network International.

Climate policy analysts said the pledge to cut carbon emissions by a billion tonnes by 2030 was the first time India had expressed an absolute emissions reduction target. And the 500 GW non-fossil fuel capacity target means almost two-thirds of installed capacity will come from non-fossil fuel energy by 2030.

“This is a truly ambitious target which will require India to more than triple the present non-fossil fuel capacity in less than a decade,” said Ulka Kelkar, an economist and director of the climate programme at the World Resources Institute, India, in a statement. “It will require additional policies as 500 GW is more than what is projected through cost minimisation alone,” she said.

Patwardhan said it was notable that India had outlined enhanced targets for the near-term, the period between now and 2030, while setting a distant 2070 target year for net-zero emissions.

Sections of climate analysts and summit negotiators have expressed disappointment that India’s target year is the most distant for a major emitter. The US and the European Union have set 2050 as their net-zero years, while China has announced 2060.

But, Patwardhan said, a comparison of the current emissions trends between China and India would necessitate India’s target year to be long after China’s. “If India were to follow China’s trajectory, its emissions would peak by 2050 and attain net-zero by 2087,” he said.

Others argue that India’s per capita emissions — emissions per person — are and will remain well below those of developed countries. Under its pledges, India would be emitting less than 3 tonnes of carbon dioxide per capita by 2030, compared with the US at 9.42, the European Union at 4.12 and China at 8.8.