I was the accidental finance minister in the government of Atal Bihari Vajpayee which took office in March 1998.

Jaswant Singh was the finance minister in the earlier 13-day Vajpayee government in 1996 and he was the hot favourite for the post again in 1998. But he unfortunately lost the Lok Sabha election in 1998 and Vajpayee was advised by the RSS, I believe, not to include in his cabinet those who had lost the Lok Sabha elections.

So, both Jaswant Singh and Pramod Mahajan were out, having lost the Lok Sabha elections. So, the million-rupee question was, who should become the finance minister?

Earlier, I had been told by friends in the know of things that I was likely to get the commerce ministry. I was extremely happy, having served in that ministry in India and abroad for seven years when I was in the IAS.

But ultimately things turned out differently. I understand that it was (L.K.) Advani who persuaded the Prime Minister to give me the finance portfolio since I was the party’s spokesperson on economic issues, Sushma Swaraj being the main spokesperson on all other issues.

This is how, purely accidentally, I became the finance minister in the Vajpayee government. I had won my Lok Sabha seat, no doubt, but I was not a leader of any consequence even in the party. My stature in government was thus completely out of proportion to my standing in the party and led to many problems.

For one, ministers who considered themselves senior to me in the party would often invite me to their office for a discussion on some issue or the other and I would oblige, with my officers in tow, if necessary.

It was the peon in my office who told me one day, with great hesitation, that this was not done. The practice was that if a minister had some issue to discuss with the finance minister, she would ask for time and come to the finance ministry; the finance minister did not go from “bhawan” to “bhawan” to discuss matters. Not only that: the finance minister had the authority to summon other ministers to the finance ministry for discussions.

After this veiled admonition, I changed the practice and everyone fell in line immediately. It was that easy. The only exceptions I made, deliberately, were for L.K. Advani, Murli Manohar Joshi and George Fernandes, though George was extremely informal in such matters and would often walk across from the South to the North Block for a discussion.

It took me a while, thus, to get over my earlier hesitation and start behaving like the finance minister of India. But in this piece I want to raise another issue.

Quite early in my days in the finance ministry, it was brought to my notice by my officers that a long pending issue was the introduction of value-added tax (VAT) at the state level. We already had Modvat at the central level and were slowly proceeding in the direction of central VAT.

I decided to take the matter up with the states and called a meeting of chief ministers. I did not go running to the Prime Minister to seek his permission to call such a meeting, nor did I consider it necessary to invite him to inaugurate the conference. I felt confident because I had realised by then that Vajpayee’s policy was to give full freedom to his ministers to function in their respective domains.

So I called this meeting, conducted it myself and at the end of it suggested to the chief ministers to form a committee to take matters further. I also suggested that Jyoti Basu, the CPM chief minister of West Bengal, should head the committee.

The suggestion was accepted unanimously as indeed was my suggestion later that a state finance ministers’ committee be constituted and headed by Asim Dasgupta, the finance minister of West Bengal.

Later, the chief ministers agreed to convert the finance ministers’ committee into an empowered one. The process I adopted became a shining example of cooperative federalism and the precursor to the present GST Council, indeed of the GST itself.

I kept the Prime Minister fully informed of the developments on this front from time to time. Never once did Vajpayee or the officials of the Prime Minister’s Office ever suggest to me that the Prime Minister or the PMO should also be involved in the exercise. Never once did they interfere with the work I was doing on this issue or any other.

I was wondering what would have happened to me if I had dared to take such an initiative in this government.

There is no doubt that the Prime Minister in our system is not merely the primus inter pares but the supreme ultimate authority in all matters. So, he does not have to assert his authority in small matters, especially of detail, to prove that he is the boss.

A Prime Minister’s authority is a given and accepted by all without demur. It is this development in the parliamentary system of government that has largely obliterated the difference between the parliamentary and presidential systems of democratic governance.

So, people have no hesitation in asking today that if such and such party has so and so leader, who do you have to match her? They forget that in our parliamentary system the people elect members of Parliament or state legislatures, who then elect their leader, i.e. the chief minister or the Prime Minister.

The phenomenon of the Prime Minister gradually emerging as the big boss did not go unnoticed even in the UK, the mother of parliamentary democracy. It did cause concern too.

Lord Hewart, the Lord Chief Justice of England, wrote a book, The New Despotism, which was published in 1929. In it he described the new despotism as an attempt to subordinate Parliament, to evade courts and to render the will or the caprice of the executive unfettered and supreme.

The book did create a flutter for some time but soon the trend of the executive assuming unbridled power became an irreversible trend, not only in England but also in all those countries that followed the Westminster model.

Even in India, where we have been so proud of our democracy, this trend has now become deeply rooted.

The Constitution of India provides for balance between the three organs of the State: the executive, legislature and the judiciary. But over time this has become dependent on the personality of the person heading these three branches.

This dependence on personalities is not a healthy development for our polity. We therefore need wide-ranging reforms today to re-establish the constitutional balance envisaged by the founding fathers of our Constitution. Until then we are destined to suffer the aberration that afflicts our polity today.

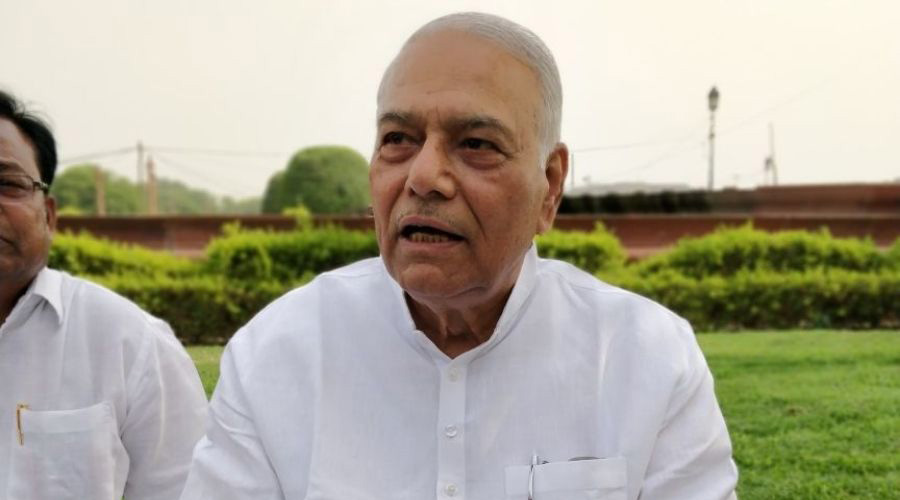

Yashwant Sinha is a former Union finance minister